- Over 25 years, human rights abuses and the consequences of the conflict, including displacement and restrictions on freedom of movement, severely hindered villagers’ access to and quality of education in southeast Myanmar. Despite the recent ceasefire agreements and increased expenditures by the Myanmar government to increase access to education among all of its citizens, children in southeast Myanmar still lack access to affordable, high quality schools within a safe physical distance from where they live.

- Financial barriers and livelihood struggles have acted as impediments to villagers accessing education over 25 years. Free and compulsory primary education is not accessible to all children in southeast Myanmar due to both upfront and hidden costs in the education sector. During conflict, financial demands were often made on villagers separate to education, which affected the extent to which they could pay for schooling. Middle and high school education is particularly hard to access as there are less schools and the fees are higher. These costs create a heavy financial burden for villagers, many of whom continue to face livelihood and food security issues.

- The teaching of minority ethnic languages remains a priority for villagers. Since 2014, Karen language and culture have been allowed to be taught in the Myanmar government schools, but reports from villagers show disparities in access to culturally appropriate education among children in southeast Myanmar. Villagers’ testimony highlights the importance of teaching Karen history, literature, and language within schools for their cultural identity. During conflict, Tatmadaw explicitly targeted Karen education schools; schools were forcibly closed or converted to a state-sanctioned curriculum.

- Due to the unresolved legacy of the conflict and their poor experience with Myanmar government schools, many villagers in southeast Myanmar mistrust the Myanmar government, and by association Myanmar government teachers. In addition to not trusting their staff, villagers also question the commitment and quality of education being provided by these teachers.

Chapter 3: Education

Foundation of Fear: 25 years of villagers’ voices from southeast Myanmar

Written and published by Karen Human Rights Group

KHRG #2017-01, October 2017

“Years ago people were happy to get a new school, but now because of the bad economy and no income, people worry about getting a new school. Also, parents’ goals for their children have changed. The parents know that their children will not get jobs if they finish school. I have seen many parents withdraw their children at primary school level. Children have to help their family, and some go to Thailand [to make money].”

Naw P--- (female, 36), Hpapun District/ northeastern Kayin State (interviewed in May 1996)[1]

“In the past our grandparents did not value education, and they also did not know the value of education. Thanks to development, the thinking of our parents has changed in terms of [how we look at] education nowadays. In the past, they used to say that you were able to eat rice whether you were educated or not. Nowadays, that idea does not exist anymore.”

Situation Update written by a KHRG researcher, Ler Doh Soh Township, Mergui-Tavoy District/Tanintharyi Region (received in November 2015)[2]

Key Findings

- Over 25 years, human rights abuses and the consequences of the conflict, including displacement and restrictions on freedom of movement, severely hindered villagers’ access to and quality of education in southeast Myanmar. Despite the recent ceasefire agreements and increased expenditures by the Myanmar government to increase access to education among all of its citizens, children in southeast Myanmar still lack access to affordable, high quality schools within a safe physical distance from where they live.

- Financial barriers and livelihood struggles have acted as impediments to villagers accessing education over 25 years. Free and compulsory primary education is not accessible to all children in southeast Myanmar due to both upfront and hidden costs in the education sector. During conflict, financial demands were often made on villagers separate to education, which affected the extent to which they could pay for schooling. Middle and high school education is particularly hard to access as there are less schools and the fees are higher. These costs create a heavy financial burden for villagers, many of whom continue to face livelihood and food security issues.

- The teaching of minority ethnic languages remains a priority for villagers. Since 2014, Karen language and culture have been allowed to be taught in the Myanmar government schools, but reports from villagers show disparities in access to culturally appropriate education among children in southeast Myanmar. Villagers’ testimony highlights the importance of teaching Karen history, literature, and language within schools for their cultural identity. During conflict, Tatmadaw explicitly targeted Karen education schools; schools were forcibly closed or converted to a state-sanctioned curriculum.

- Due to the unresolved legacy of the conflict and their poor experience with Myanmar government schools, many villagers in southeast Myanmar mistrust the Myanmar government, and by association Myanmar government teachers. In addition to not trusting their staff, villagers also question the commitment and quality of education being provided by these teachers.

Introduction

This chapter will present villagers’ priorities and experiences with education services in southeast Myanmar over 25 years, and ask what are the problems facing both villagers and local service providers now and how is this different from the past. The state education system has long suffered from a critical lack of resources and skills. While in recent years expenditures on education[3] and school enrolment rates[4] have improved, particularly since 2012 following the signing of the preliminary ceasefire, the targeted destruction of the Karen education system, the total lack of investment by the Myanmar government in communities, and the displacement and abuse of Karen communities mean that the education system in southeast Myanmar has struggled to fully recover from the repression and conflict that affected every aspect of Karen society including schools, and arguably continues to affect it. While the lower levels of militarisation and insecurity resulting from the ending of formal conflict have provided villagers with greater ease of access to education, villagers continue to also identify militarisation as a barrier to accessing education.[5]

An analysis of villager testimony over KHRG’s 25 years reporting period shows that while there have been improvements in access to education in southeast Myanmar, access to quality education still remains particularly difficult for children in rural areas and for those displaced as a result of conflict, many of whom still lack access to affordable schools within a safe physical distance from where they live. Furthermore, many of the concerns voiced by villagers about the current state of education in southeast Myanmar mirror villagers’ concerns throughout KHRG’s 25 years including distrust and suspicion of government provided services, insufficient resourcing of educational services, a lack of respect for Karen language and culture within schools, and ongoing barriers to accessing affordable, quality education.

As a mechanism to preserve and reproduce Karen language, culture, and history, the right to education has remained a central concern to Karen villagers and their identity both prior to and during the ceasefire period. Villager testimony shows that the relationship between education and ethnic identity remains as strong now as it did during the context of formal armed conflict. As Myanmar transitions from a state of ceasefire towards a fragile peace, further investment and action will need to be taken by the Myanmar government in consultation with local communities, ethnic education departments, and CBOs, in order to ensure that all children in southeast Myanmar are able to fully realise their right to a culturally appropriate education.

National and international legal obligations

According to Article 26(2) of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), education shall be directed to the full development of the human personality and to the strengthening of respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms. It shall promote understanding, tolerance and friendship among all nations, racial or religious groups, and shall further the activities of the United Nations for the maintenance of peace. The right to mother tongue language education is recognised in several international instruments that the Myanmar government has agreed to including Article 29(1)(c) and 30 of the Convention of the Rights of the Child (CRC) and Article 14 of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).

Over the past decade, the Myanmar government has taken steps to bring its national legislation and policies in regard to education in line with international human rights standards. The right to education is enshrined in Article 366 of Myanmar’s 2008 constitution, which guarantees access to primary education to all children.[6] Additionally, on September 30th 2014, President Thein Sein signed the National Education Law (NEL) which included provisions on the introduction of mother tongue-based learning.[7] In the wake of student and teachers’ union protests, amendments were made to this law in 2015 including provisions permitting the use of ethnic languages along with the Myanmar language as a classroom language in basic education (Article 43, b).[8] The first National Education Strategic Plan (NESP) was launched in February 2017 which allows for the learning of ethnic languages and culture within schools and the use of ethnic languages as a classroom language.[9] The NESP confirms the Myanmar government’s commitment to inclusive education and to the creation of a decentralised education system. Despite positive reforms in the education sector over the last few years however, Karen villagers continue to face major challenges relating to school access, retention, inclusion, and quality assurance of education standards, showing the continuation of some challenges faced by villagers throughout KHRG’s 25 year reporting period.

Villagers’ access to education facilities and service

“Apart frome ducation we have seen the Burma [Myanmar] government struggles to build schools in some places, [but not others] and we have seen the children [in areas where there are schools] have more chances in their studies. If we look at the period of war in the past the children could not go to school. They always had to flee. Because of that many children lost [the chance] to gain an education. We cannot compare the past to the present time anymore [because change has taken place]. Villagers are therefore so pleased that their children can go to school as well as possible [as easily as they can no win comparison to the past], but education is still lacking in many places and villages.”

Situation Update written by a KHRG researcher, Kyainseikgyi Township, Dooplaya District/southern Kayin State (received in February 2015)[10]

KHRG reports show that one of the most notable factors influencing access to education among children in southeast Myanmar over the past 25 years has been the level of military activity in their area. Most notably during the period from 1992-2012, education was severely disrupted due to militarisation including Tatmadaw’s[11] destruction of schools and educational buildings and the disturbance and hindrance of students and teachers by military actors, particularly the Tatmadaw.[12] During this time, villagers reported that schools were shut down or targeted by the Tatmadaw. According to villager Saw Fj--- in 1999:

“Before the SPDC [Tatmadaw] came, we had a school. But after they arrived, our school, our village, and all of our belongings were destroyed.”

Saw Fj--- (male, 30), quoted in a Thematic Report written by a KHRG researcher, Fk---village, Kyainseikgyi Township, Dooplaya District/southern Kayin State (published in March 2000)[13]

As a mechanism to preserve and reproduce Karen language and culture, education is essential to Karen villagers’ ethnic identity. As such, these targeted attacks on schools were another means to eradicate non-Bamar ethnic identities. According to Saw Fi--- in 2000:

“Now our children can’t write or speak their language because they don’t have a chance to learn at school. Our literature has disappeared and is destroyed. The Burmese are fighting us this way.” Saw Fi--- (male) quoted in a Commentary written by a KHRG researcher, Kler Lah relocation site, Htantabin Township, Toungoo District/ northern Kayin State (published in October 2000)[14]

In addition to the targeted looting and destruction of Karen educational facilities, villagers were also blocked from building new schools[15] or did not do so out of fear that building new schools in their villages would increase the likelihood that they would be targeted by armed actors. For example, villagers in the Meh Kreh area of Hpa-an District in 1998 had their villages burned down, but feared that building new schools would attract a second Tatmadaw attack. The attacking of school buildings by Tatmadaw was perceived by villagers to have direct intention of repressing their ethnic culture. In the experience of villagers in the Meh Kreh area, the Tatmadaw suspected the teachers in these schools of being trained in a KNU school and, by association, as being in support of a Karen ethnic armed group. As a result of the government and Tatmadaw suspicion that KNU schools promoted ethnic insurgency, the children in these areas had no access even to primary school.[16] Furthermore, movement restrictions and the danger of landmines or capture and abuse by Tatmadaw soldiers operating under a shoot-on-sight policy made it impossible for both teachers and children to travel to schools in other villages or towns.[17]

Coupled with the destruction and closure of schools, villagers have also endured other human rights abuses such as systematic violence, unrelenting forced labour, destruction of goods and property, physical torture, and forced relocation. As a result, villagers often chose to strategically displace themselves to avoid further abuses. These abuses directly affected education as displaced villagers were unable to establish permanent schools. Villager Naw D--- recounts her struggle accessing education throughout years of abuse from Tatmadaw:

“Because of the SPDC [Tatmadaw] operations, we cannot count how many times we have fled in the forest. There was one year when we had to leave our school and we couldn’t study at all for the whole year. I had to repeat the same grade the next year.” Naw D--- quoted in a Field Report written by a KHRG researcher, Hpapun District/ northeastern Kayin State (published in June 2008)[18]

In addition to the physical barriers in accessing education brought on by systematic abuses, villagers have continually reported that insurmountable economic barriers prevent children from attending school. Throughout KHRG’s 25 years, parents who wished to send their children to school often have had to pay for tuition fees, school materials, and other arbitrary fees. The demands for additional fees at school placed further strain on family resources already constricted during the conflict by the excessive demands of the Tatmadaw and EAGs.[19] Faced with demands to supply materials for forced labour, extortion and the forced payment of fees to armed groups particularly in the 1990s and 2000s, most families didn’t have enough money left to pay the costs of sending their children to school. According to a schoolteacher in a Myanmar government school in Mergui-Tavoy District in 1995,the main reason students were absent from school was that their parents were poor.[20] Furthermore, throughout both conflict and a fragile peace, livelihood struggles have restricted children’s access to education. Parents, who were unable to maintain the livelihood needs of their families on their income alone, particularly when their livelihood security was threatened under conflict by excessive demands on their time and finances through forced labour and other abuses, often relied on the extra support from their children through labour or to help out at home.[21]

Since the ending of formal conflict, the Myanmar government has increased its expenditure on education as evidenced by KHRG reports of new government schools opening in all seven locally defined Karen Districts. Despite increased financial investments by the Myanmar government to increase access to education among all of its citizens, reports from community members show that many children in southeast Myanmar still lack access to affordable schools within a safe physical distance from where they live. In fact, many of the concerns voiced by villagers in regard to accessing education prior to the ceasefire period still persist today including physical and economic barriers to education, insufficient livelihoods,[22] food security issues,[23] and an insufficient number of schools[24] and school teachers. The situation is particularly difficult in very rural areas where there is poor investment resulting in lower access to education. As mentioned by a community member in Nyaunglebin District:

“For the schools that the leaders [from the education department] can reach, we have seen that [the education situation] has been improved for [by] villagers that [are] actively [striving] for [better] education. We are so worried that there is poor support for the education of the villagers in the rural areas, so that the things that should be happening are not happening.”

Situation Update written by a KHRG researcher, Nyaunglebin District/ eastern Bago Region (received in July 2014)[25]

Villagers in rural areas of southeast Myanmar still face insurmountable financial obstacles in sending their children to school. In the post-ceasefire period, villagers are still required to make significant financial investments in order for their children to attend school. One villager reported “although education has improved after the 2012 preliminary ceasefire, students do not have access to free education and they still have to pay schools fees.”[26] In addition to these fees, some villagers also have to hire and provide financial support for teachers including paying for their food and accommodation costs,[27] travel expenses,[28] and salaries,[29] creating a heavy financial burden for villagers’ already experiencing livelihood and food security issues. A villager from Toungoo District reported in 2015:

“The villagers themselves have to find school teachers and have to financially support them. For the large villages, they have money [due to the higher number of villagers able to provide support]. Therefore, there is no difficulty for them, but for the small villages [with fewer people], villagers have no money to support the teachers and they also do daily work to earn their meal. Thus, the children are not able to go to school, but instead have to help their parents to [do] house work.” Situation Update written by a KHRG researcher, Htantabin and Thandaunggyi Township, Toungoo District/northern Kayin State (received in July 2015)[30]

For families experiencing livelihood issues, little progress appears to have been made over 25 years of KHRG reports, as parents and children often have to prioritise income generating activities over receiving an education. As noted by a villager from Dooplaya District:

“For the parents who earn daily wages, they are not able to take their children to school; some children have to look after their younger brothers and sisters and some children have to assist their parents. Some parents of children who have finished primary and middle school were not able to keep supporting their education so [the children] had to quit school and help their parents. ”Situation Update written by a KHRG researcher, Kyonedoe and Kawkareik Townships, Dooplaya District/southern Kayin State (received in November 2014)[31]

Location of schools

Another factor in determining access to education is the type of governance where a school is located. Since the 1970’s, the KNU-administered Karen Education Department (KED) has developed an expansive education system that prioritises the learning of Karen languages and ethnic identity. As a result, there have historically been and continue to be substantial differences between the Myanmar government administered and KNU administered education systems, which has its own teachers, policies, curriculum, and management. While the village schools that are in KNU-controlled areas receive support from the Karen Education Department (KED) from the KNU, such as books, pens, pencils, and other kinds of materials for the schools,[32] locally led or KED schools in mixed control areas struggle to build enough school facilities and provide students with quality teachers and education materials. Lacking additional financial support from for their children. A villager from Dooplaya District reported to KHRG in December 2014:

“The leaders and are a leaders are also struggling [to build schools] in the places where the Burma government has not done anything yet, but not all places [are struggling]. We need more support for education.”

Situation Update written by a KHRG researcher, Dooplaya District/ southern Kayin State (received in December 2014)[33]

This is particularly true in villages with smaller numbers of households. In these areas, villagers report that the education system is poorly supported by the Myanmar government. In 2014, villagers in Thandaunggyi Township, Toungoo District, submitted a request to the Myanmar government for the cost of the materials for the school building and its construction, based on the number of households and students, but the number of households was too low for the government to support the school.[34] This suggests that the government does not value each child’s access to education equally, as children in rural areas continue to be denied schooling. Villagers living in an area without a school who are unable to receive financial support from the Myanmar government have chosen to build their own self-reliant schools using their own funding and employing teachers from the local community and, in some cases, work with other Myanmar government schools.[35] The problem of schooling in rural areas of southeast Myanmar is particularly apparent in the lack of middle and high schools. Children who are able to pass seventh and eighth standards[36] must finish their studies in the towns, refugee camps, and other places where high schools are located.[37] Problematically, this results in some primary school children not continuing to middle and high schools because of lack of access. According to one community member from Dwe Lo Township:

“There are a few high schools in Dwe Lo Township. Most of the schools are middle schools and primary schools. The villages that have many households set up middle schools and villages which have fewer households set up primary schools. All school age children have the chance to go to school in Dwe Lo Township. Some children who finished middle school go to refugee camps and some go to the city to continue their study.”

Situation Update written by a KHRG researcher, Dwe Lo Township, Hpapun District/ northeastern Kayin State (received in February 2013)[38]

Traveling long distances to access education is particularly difficult for girls. Due to the fear of their daughters being subjected to physical or sexual assault, parents are more hesitant to send their girls away to a distant school than their boys. Given that most middle and high schools are located in towns and cities, many girls from rural areas are unable to continue their education past the primary level.[39]

While the financial abuses and serious livelihood restrictions that were pertinent during the conflict and acted as significant barriers to accessing education have reduced, the above cases show that villagers in southeast Myanmar continue to face financial barriers and livelihood struggles that prevent many children accessing education. Additionally, the persistent lack of investment in education in rural areas has done little to improve livelihood struggles for rural communities and opportunities for rural children.

Quality of education in southeast Myanmar

Interviews with community members over KHRG’s 25 years reporting period show that as access to education in some parts of southeast Myanmar has started to expand, villagers have become increasingly concerned with the quality and standard of education in southeast Myanmar. While reports from villagers particularly in the 1990s and 2000s highlighted the need for better quality education, interviews with villagers often focused more heavily on the impact of the prolonged conflict on children’s access to education. Since the ceasefire period, direct attacks on educational facilities have diminished but ongoing militarisation continues to disrupt education and has resulted in schools closing when fighting occurs in the area.[40] Throughout armed conflict, villagers repeatedly experienced forced labour, forced relocation, displacement, violence and abuse at the hands of the Tatmadaw and ethnic armed groups. In an effort to evade encroaching army units, most notably Tatmadaw, villagers often fled into the forest. This subsequent displacement negatively impacted not only children's access to education but also the quality of education that they could receive, such as the conditions under which they could continue their study:[41]

“Because the SPDC [Tatmadaw] is active near my neighbours’ village, we have had to flee from our village. The school year is not finished yet so the children have had to continue their schooling under the trees in the jungle.” Saw L--- (male, 59), L---village, Lu Thaw Township, Hpapun District/ northeastern Kayin State (interviewed in January 2007)[42]

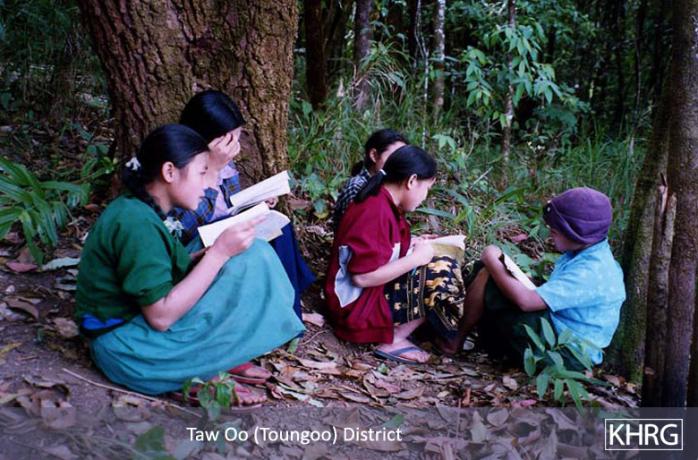

For the villagers in the forest, there was virtually no access at all to schools. In order to continue teaching their children in hidden sites, parents constructed makeshift blackboards against trees or constructed rudimentary school shelters which sometimes served as basic schools for displaced children from several communities. While displaced communities quickly restarted schools at forest hiding sites, the constant disruptions in education coupled with the lack of facilities and education materials made it impossible for children to receive a quality education. Displaced communities were fortunate if a teacher was displaced with them; many children continued their education by whatever means possible in these jungle camps without formally qualified teachers, curricula or materials. Many villagers in 2017 remain displaced in refugee and IDP camps, affecting their choices with regard to accessing education, and the stability of their access to education itself.

Additionally, throughout 25 years of reporting, villagers who have not been displaced have also raised their concerns about the quality of education in their communities. Villagers with access to schools run by the Myanmar government have consistently reported issues with quality assurance standards prior to and after the cessation of formal conflict. Myanmar government schools lacked minimal resources, the teachers were underpaid, and the curriculum was strictly Bamar, problems which continue to persist. Community members particularly in rural parts of southeast Myanmar also reported to KHRG that the Myanmar government supplied teachers often left after a few months never to return. Instead, they stayed in the provincial towns and collected their state teaching salary despite not working.[43] Because the schools were understaffed, the villagers often hired people from within the village to teach in the schools alongside the Myanmar government teachers, although they lacked formal qualifications and the villagers did not receive government funding for these local staff.[44] In many areas, villagers stated that they did not have sufficient funds to construct a school building or hire qualified teachers, so many children missed out entirely on formal education and the majority never had a chance to study beyond primary school.[45] These issues highlight that even when education was available during the conflict, the quality was unacceptable.

As conflict has lessened, villagers’ main concerns have also stayed the same with regard to problems with Myanmar government services. Villagers continue to report their dissatisfaction with the quality of teachers[46] and school facilities,[47] the non-integration of Karen culture within the education curriculum,[48] and recognition of educational certification received in non-state schools.[49]

Since the 2012 ceasefire, the Myanmar government has made efforts to expand education access in remote areas due to the improved security situation. In spite of improvements in availability and accessibility of schools, many villagers in rural areas still lack access to adequate school facilities and education materials. Poor school resources affect not only some Myanmar government but also for some KED schools. For example, one KHRG community member from Toungoo District reported in 2016 that students in his area do not feel secure because the KED School they attend does not have a secure roof or floor. Moreover, quality is further compromised due to overcrowding in the schools in some villages so students do not have enough space to learn.[50]

Villagers’ concerns with Myanmar government teachers have also not lessened. As part of its efforts to improve access to education for students in southeast Myanmar, the Myanmar government intensified its efforts to recruit a sufficient number of government teachers to teach in these areas. Due to the unresolved legacy of the conflict and their poor experience with Myanmar government schools, many Karen villagers mistrust the Myanmar government, and by association Myanmar government teachers. In addition to not trusting their staff, villagers also question the commitment and quality of education being provided by these teachers. A villager from Toungoo District describes the low standard of education in his area due to poor teacher quality:

“IfI have to talk about education, I can say that the teachers need more capacity building – they are not qualified. Because of this, the kindergarten and primary students have to pay tuition [for private after school classes].[51] The situation is that they will only [be able to] pass their grade if they pay the tuition. Another thing is the teachers themselves can not read and pronounce [words] properly; wecan find those kinds of situations. Moreover, the teachers can not explain the lessons very well, so they mostly let the students memorise the lesson [use rote learning techniques].”

Maung A--- (male, 34), Fa--- village, Thandaunggyi Township, Toungoo District/ northern Kayin State (interviewed in March 2015)[52]

The poor education provided by Myanmar government staff affects not only villagers’ relationships with the teachers, it also has financial consequences. Due to the low quality of teaching there now exists an expectation in many areas that students should pay for private after-school lessons if they want to be able to pass their classes, adding an additional financial barrier to ensuring equal access to education for all children. This situation has created deeply unequal education outcomes. Students who are unable to afford private lessons are further disadvantaged.

The poor quality teaching by Myanmar government staff is further problematised by teacher absenteeism. Similar to villagers’ reports of government supplied teachers leaving after a few months never to return,[53] recent reports from villagers show that Myanmar government appointed teachers often have to travel to town in order to attend training or pick up their stipends, which hinders students in rural areas from receiving the same quality education as students from urban areas. According to a community member from Dooplaya District:

“Both teachers hired [by the villagers] and those appointed by the government [and sent to teaching posts in different areas of the country] have to attend training or sit exams once every three or four months. [The training sessions or exams] take between two days and one month [to complete], and because there are no teachers to replace them [while they are in training or sitting exams] it disrupts the education of the students.”

Situation Update written by a KHRG researcher, Kyonedoe Township, Dooplaya District/ southern Kayin State (received in February 2014)[54]

In addition to the lack of capacity of Myanmar government teachers to provide quality education in southeast Myanmar, trust in teachers is further undermined by cases of abuse. Community members have reported several cases of abuse perpetrated by government teachers against students. Reports by KHRG confirm incidents of teachers beating students for not passing their monthly exams[55] and subjects[56] or were unable to follow the government curriculum.[57] For example, in C--- village, Pa Heh village tract, primary school students who did not pass their examinations were punished by their teacher who made them sit down and stand up 500 to 1,000 times.[58]

The poor quality teaching and abuse by government teachers has only exacerbated villagers’ mistrust of government provided services, a legacy created during formal conflict, but one that cannot be resolved without further action by the Myanmar government to improve the quality of education services in southeast Myanmar including building the capacity of government teachers to provide high quality and culturally appropriate education, without discrimination.

Towards an inclusive education: Teaching Karen culture and languages within schools

A significant source of contention with regard to Myanmar government education is the lack of inclusivity of Karen culture into the education system. Despite villagers’ increased access to education in southeast Myanmar, a long history of forced assimilation on the part of the Myanmar state and Tatmadaw, particularly within the education system, has created a deep-seated fear and mistrust of the government among Karen villagers which still persists today. The development of educational services outside the state system arose in self-reliance in response to the lack of access to schools among children in southeast Myanmar, but also as a means to resist ‘Burmanisation’[59] through the development of an education system that respected and preserved Karen culture. The KNU-administered Karen Education Department (KED) has always prioritised the learning of Karen languages and ethnic identity. As such, KED administered education has and continues to play a significant role in preserving and reproducing Karen language, culture, and history.

According to KHRG reports, forced assimilation policies implemented by the Myanmar government has resulted in many KNU administered schools being forcibly closed or destroyed and Karen language, literature, and traditions were banned from classrooms, particularly prior to the 2012 ceasefire. During this time, villagers struggled to keep schools open unless they hired Myanmar government-sanctioned teachers as officers were suspicious of any service which was not directly controlled by the Tatmadaw. Throughout southeast Myanmar, many villages used to have primary schools supported by the KNU or schools they set up and ran entirely by themselves, but these were systematically forced to shut down by the Tatmadaw. In order to open their schools, villages were required to obtain the regime’s approval to run a school, to pay all the costs and salary of a Myanmar government-trained teacher, and to teach the official Myanmar government curriculum.[60] According to one villager from Hpa-an District:

“If you want a school, the teachers must be Burmese government teachers, or else they will kill them. They really will, the Burmese will kill them. ... They will never allow us to study Karen [language]. The teachers must come from Burma with their Burmese teacher’s card. Our Karen teachers have no Burmese teacher’s cards, so if they see our teachers they will kill them. That’s why we can’t try to open a school.”

Saw Fd--- (male, 43), Fe--- village, Hpa-an District/ central Kayin State (interviewed in April 1998)[61]

These attacks on Karen education, including teachers of self-reliant Karen schools and the school facilities, accompanied deliberate attacks on villages and the deliberate targeting of Karen people by the Tatmadaw. The Tatmadaw inflicted abuses on all parts of Karen culture, including the education system, demonising Karen culture as rebellious and accusing Karen people of supporting or being ethnic insurgents.

In seeking to stamp out Karen culture, the Myanmar government curriculum specifically forbade the teaching of any languages except Burmese and English. Villagers who wished their children to be literate in their mother tongue had to find someone to teach their children outside of official school hours or organise a summer course during their school break,[62] often at great risk

“The subjects that they teach in school are English, Burmese, and math.They don’t allow the teaching of ethnic groups’ languages. In our village there are both Karen and Mon people, and both of them want to teach their own language. But the Burmese do not allow the children to learn it. In my opinion this is one of their ethnic cleansing policies.”

Saw Ff--- (male, 34), Fg--- village, Waw Raw Township, Dooplaya District/ southern Kayin State (interviewed in August 1999)[63]

Since 2014, Karen language and culture have been allowed to be taught in Myanmar government schools as part of Myanmar’s National Education Law, but according to reports from villagers, there are disparities in access to culturally appropriate education among children in southeast Myanmar. In some areas such as the Dweh Hkee area, Leh Doh Soh Township, Mergui-Tavoy District, villagers have reported that Karen language, culture, and history can be taught in the schools in their villages.[64] KHRG reports show that Karen is generally taught before and after school hours, showing that the teaching of ethnic languages continues to not be accommodated in Myanmar government curriculum.[65] The following excerpt of a situation update from Mone Township, Nyaunglebin District in 2016 shows that whilst Karen can be taught it is generally taught before and after formal school hours:

“Th[e] [new] school gives the students an opportunity to study Karen language and culture so one [Karen subject] teacher was chosen from the village.This Karen subject teacher gets a salary from Myanmar/Burma government as well. The [students] study Karen language and culture from 08:30 am to 09:00 am in the morning before school starts and then from 14:30 pm to 15:15 pm in the afternoon [each day]. They [students] are given an opportunity to study Karen language and culture in the morning and in the afternoon everyday of the week.” Situation Update written by a KHRG researcher, Mone Township, Nyaunglebin District/ eastern Bago Region (received in August 2016)[66]

Other KHRG reports show that many villagers lack access to Karen language instruction with many government-led schools still not ensuring students’ right to mother tongue language education. A villager in Mergui-Tavoy reported to KHRG in 2015:

“At this time, we see [the] Burmese government tells [us] that they are going to give the rights [to teach theKaren language] to the local Karen school. It says that Karen language will be taught in the class. Not in the extra class (extra time outside of official school hours). In spite of saying like that, we clearly see that school teachers do not teach Karen language in the class.”

Situation Update written by a KHRG researcher, Mergui-Tavoy District/ Tanintharyi Region (received in November 2015)[67]

In addition to the lack of teaching in Karen, and of the Karen language, numerous reports from community members continue to express a deep mistrust of government teachers and resentment towards the expansion of Myanmar government authority through education provision. In recent years, the Myanmar government has been investing in the local (KED) government schools and sending their own trained teachers to teach in them which have caused tension among Karen teachers. A teacher from Fh--- village recounted her negative experiences working with government teachers:

“I have been teaching since [from] 2006 till 2015 andI have faced too many things [difficulties] with Myanmar government teachers and this school was not built by [the] government, it was built by the villagers of Fh--- village as a self-rely [self-reliant school]. But in 2014, Myanmar government teachers entered into this school and one teacher from the Myanmar government side was posted as an officer in charge of the school although the school was not built by the government. Therefore, one of the local teachers at that school was not feeling well [happy] about that and said that ‘these Myanmar government teachers just come to be a master in our school’”

Situation Update written by a KHRG researcher, Kyonedoe Township, Dooplaya District/ southern Kayin State (received in August 2015)[68]

In some cases, the Myanmar government has expanded state structures in southeast Myanmar without taking into account existing local activities and services showing a lack of transparency and consultation with local stakeholders.[69] In a 2014 interview with KHRG, a villager from Thaton District recounted the experiences of teachers in his area:

“Regarding a problem which happened in the education sector, since the government sent too many of their teachers to mountain villages, some of the local teachers who the Karen Education Department [KED] had already selected became jobless. What is more, it has made the burden on the villagers heavier as they have to provide the food for the government teachers.”

Situation Update written by a KHRG researcher, Hpa-an Township, Thaton District/ northern Mon State (received in July 2014)[70]

Community members’ current concerns with Myanmar government expansion and the lack of support for Karen education are worsened when they are forced, as in the excerpt above, to take financial responsibility for the Myanmar government teachers. Additionally, the abusive policies that underpinned forced repression and assimilation of Karen into Bamar culture is still tied to the Myanmar government education system, making many community members unwilling to welcome new government imposition in this area.

Villagers have repeatedly turned to self-reliance when the Myanmar government has failed to provide the necessary services for them, and when Tatmadaw has targeted every aspect of Karen culture including education. However, whilst many children have received a thorough education through schools run by KED, CBOs or community members in refugee camps, these education facilities continue to not be recognised by the Myanmar government. Since non-state education qualifications are not recognised by the Myanmar government, graduates from these schools find it difficult to enter the government education system, access job opportunities in Myanmar, or apply for universities abroad. In a 2016 interview, a community member from Dooplaya District reported not only immediate financial consequences but also longer term limitations on job opportunities because of this system:

“Even if our children passed [the KNU] schools they still have to take government examination inorder to get certificate. We have to spend a lot of money so it caused problems for the [villagers] who do not have enough money. So even if they passed [the KNU] school they can only do ordinary jobs. They only gave [job] opportunities to the people who passed the Myanmar government schools [not the KNU schools]. For the people who passed government school they have a government certificate with them and if they are required to show their certificate, they can show it.”

Naw Fb--- (female), Fc--- village, Kyainseikgyi Township, Dooplaya District/ southern Kayin State (received in January 2016)[71]

The lack of formal recognition of credible qualifications issued by non-state schools has created an inconsistent quality standard of education in southeast Myanmar and further marginalises Karen villagers. For the children of villagers who were displaced during the conflict, this lack of accreditation further isolates and acts as a significant barrier to their successful and supported reintegration into Myanmar society. In combination with an ongoing mistrust of Myanmar government services and staff, the Myanmar government’s lack of formal accreditation afforded to many educated Karen youth does little to build a relationship between the Karen community and the Myanmar government, or address the hardships that Karen villagers have lived through due to decades of Myanmar government and Tatmadaw policies. This trust can only be fostered through transparent and participatory collaboration between the Myanmar government and ethnic education departments to ensure that villager’s concerns and expectations regarding the provision of culturally appropriate education are respected.

Education for community development and peace building

In the wake of these exclusionary practices and policies, villagers over 25 years of KHRG reports have utilised various resistance strategies to directly counter the marginalisation of Karen culture and language within the education system including arranging for teachers to teach the Karen language outside of school hours,[72] building self-reliant (independent) schools,[73] and raising the Karen flag in front of a school.[74] Villager testimony throughout KHRG’s reporting period shows that education itself has and continues to be a form of resistance and an essential way to maintain Karen culture. In the words of one villager from Kyaukkyi Township, Nyaunglebin District in 2016:

“I think that eventhough we can not fight with our guns, we can fight with our words or pens.”

Naw Fi--- (female, 24), Fj--- village, Fj--- village tract. Kyaukkyi Township,

Nyaunglebin District/eastern Bago Region (received in December 2016)[75]

The importance of education as a means to safeguard villagers’ ethnic language, culture, and identity has not diminished during the ceasefire period, but has taken on new significance as Myanmar transitions from a state of ceasefire towards a fragile peace. Given the legacy of conflict and the Myanmar government’s attempts at forced assimilation through education, villagers continue to distrust government-led services and view the expansion of government-led education into Karen areas in the wake of the formal ceasefire as another means to expand government control over Karen communities. As villager testimony highlights, Karen identity is inextricably linked to the provision of culturally appropriate education. The expansion of government-led education services, which fail to integrate Karen culture within the education curriculum, are viewed by some villagers as a continued attack on Karen culture, particularly when they replace existing locally led services. A villager from Thaton District expresses his concern over the expansion of government run education services which displaced KNU schools:

“Our enemy [Burma / Myanmar government] entering into [attacking] our community is the biggest challenge facing my community. The Burmese do not attack us by [though] militarisation, but they attack us by [taking control over our local] education system. Therefore, it decreases our [Karen] school numbers and there are just a few Kaw Thoo Lei [Karen] schools left in my area. I think all of the schools in my area possibly replaced by Burma/Myanmar government schools.”

Saw Fo--- (male, 27), Fp--- village, Bilin Township, Thaton District/ northern Mon State (interviewed in December 2016)[76]

Saw Fo---’s testimony highlights the continued underlying tensions between Bamar, Karen and other ethnic groups in southeast Myanmar during the ceasefire period. Disagreements regarding culturally appropriate education risk further exacerbating these tensions and can hinder peace building as Karen culture is perceived to be under threat again from the majority culture. The opportunity for suitable education to stabilise communities and bring about improvements is evident in the testimony of this villager from Hpapun District, where education is closely linked to being able to protect Karen culture from oppression:

“As we are living in the community, we want to improve thee ducation for [our] children. This is for the future. If our children are able to read and write, they will be able to produce good ideas [about] how to improve their community. if they [children] are well-educated, they will be able to improve theirlives and [their] communities. If they can improve their communities they will become good and useful citizes. if we do not have knowledge or if we are not literate, we cannot go anywhere and we will be going around [and around] here [in] a circle [not making any progress]. Therefore, we will continuously be suffering from oppression.”

U Fm--- (male, 53), Fn--- village, K’Taing Tee Village Tract, Hpapun Township, Hpapun District/northeastern Kayin State (received in January 2017)[77]

It is evident from these testimonies that education has the chance to either stabilise or undermine efforts towards peace in southeast Myanmar. Investing in high quality, community-led, culturally appropriate education, with equal access in both rural and urban areas, would show a long-term investment in, as well as a protection and strengthening of, Karen culture. Alternatively, forcing a Myanmar government agenda for education, without support of Karen language, staffing and traditions, will only serve to exacerbate that tensions that remain unresolved, according to 25 years of KHRG reporting, including the lack of respect for Karen language, poor experiences of Karen students at the hands of Myanmar government teachers, the poor quality of services afforded to Karen villagers and the maintenance of a terse relationship between Myanmar government staff and Karen communities.

Conclusion

Political and legal reforms coupled with greater investments in education by the Myanmar government have led in some parts of southeast Myanmar to better access to education in Karen areas, as well as the introduction of Karen language being taught within government schools. While this has been viewed by villagers as a positive step, for many villagers’ access to education remains blocked by the lack of school facilities, particularly at higher levels, that are a safe distance from or within their community. Villagers continue to face financial barriers and livelihood struggles, which have impeded their access to education over 25 years. Upfront and hidden costs in the education sector continue to hinder children in southeast Myanmar from accessing education, particularly middle and high school level education.

Villagers’ concerns about education are furthered by sub-par teaching in available schools and the continuance of fees for some aspects of education, notably extra tuition classes to compensate for the poor quality and attendance of Myanmar government teachers. Additionally, the Myanmar government has not taken any action to implement the teaching of Karen culture and history within the government administered education system nor has the government taken any steps toward teaching subjects in Karen languages. Reports from community members over KHRG’s 25 years reporting period showcase the strong link between teaching Karen languages and culture within schools and the pride in maintaining Karen identity. As such, villagers have always fought to provide a culturally acceptable education to their children, even under trying and dangerous circumstances where doing so put them at direct risk.

Furthermore, the Myanmar government’s lack of transparency and consultation with ethnic education departments, villagers, and ethnic community based organisations in southeast Myanmar when expanding government-led education services continues to perpetuate villagers’ mistrust of Myanmar government schools, and by association Myanmar government teachers. The need to improve the quality of education and unresolved legacy of mistrust in government led services will require greater coordination and communication between the Myanmar government and ethnic education departments. The Myanmar government will also need to ensure that all schools are equipped with sufficient funds, resources, and teachers who have the knowledge, skills and attitude to provide culturally appropriate education and respond to Karen children’s needs. Despite the implementation of some administrative and legal measures, further action needs to be taken by the Myanmar government to ensure equal access to the right to education for all children in southeast Myanmar, with particular emphasis on the support of minority ethnic cultures through the education system.

The primary schools in Khaw Hta and Yah Aw villages, Nyaunglebin District, were among the buildings burned by Tatmadaw troops from LIB #589 and LIB #350 at the start of December 2004. The people of both villages fled into the forest, where within a few days the schoolteachers had set up makeshift blackboards and students from both villages tried to continue learning. [Photos: KHRG][78]

This photo from a 1997 KHRG report shows a Tatmadaw ‘government’ middle school in Noh Aw village, until the village was ordered to move, the ‘government’ teacher fled, and Tatmadaw troops came and burned the school and much of the village. Though it was a ‘government’ school, the villagers had to pay for the construction, build it, pay for and support the teacher, and pay for all school supplies. This is normal, as all the Tatmadaw does is send a teacher, and then burn the school. [Photo: KHRG][79]

This photo shows school teacher Naw T---, who is 19 years old, teaching a lesson to her students at the P--- internally displaced village in Thandaunggyi Township, Toungoo District, in November 2002. Having to close whenever Tatmadaw patrols are around, her school can stay open on average only one week out of every month. [Photo: KHRG][80]

After their villages and schools were burned by Tatmaaw Light Infantry Division #66 in December 1999/January 2000, a village teacher teaches some of the children from three villages in western Lu Thaw township, Hpapun District, that have been displaced in the forest. [Photo: KHRG][81]

This photo was taken on June 29th 2015. The photo show a groups of students learning and taking a class on the ground-area underneath a house, as there is no school room in Shwe Nyaung Pin village, Thandaung Town, Toungoo District. As Shwe Nyaung Pin villagers want their children to get access to education, they have rented this space for their children to study in. The building does not have adequate space, fresh air or light and leaks in the rainy season. Parents requested support from the Myanmar government but have not received any response. [Photo: KHRG][82]

This photo was taken on December 1st 2015. It shows Ku Pyoung village’s primary school, located in Thandaunggyi Township, Toungoo District. This school is very old and in need of repair and renovation. It is a self-reliant school that has been managed and supported by villagers for a long time. Villagers have already applied three times for financial support from the Myanmar government but have not received any response from the government. The students and teachers report that they do need feel safe and secure due to the old building. [Photo: KHRG][83]

Students who have just finished their school year at an IDP camp in Hpapun District return to their home villages. The students are shown here on March 20th 2009 hurriedly crossing a Tatmadaw-controlled vehicle road while Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA) soldiers take security. Because of insecurity and a lack of educational facilities at their home villages, which remain outside of Tatmadaw- controlled areas, these students must take this risky journey simply to access schools. [Photo: KHRG][84]

This photo was taken in December 2014. It shows children in the rural hill village of Mae K’Ler Kee village, Dooplaya District. There are only around 20 families remaining in the village due to mass displacement during conflict. Very few agencies and organisations are able to reach this area. Villagers, with the help of the village head, agreed to hire a local community member to teach them with school materials, such as books, for 15,000 Baht (US$435.16) per month, in order for their children to study. Prior to 2014 the children in this village had not attended school. [Photo: KHRG][85]

This photo was taken in July 2002. It shows students and teachers of the school at L--- hiding site in Lu Thaw Township, Hpapun District. This school only teaches classes from Kindergarten to Third Standard (Grade Three). Very few IDP schools are able to teach beyond primary school (Standard four) level because most of the teachers never had a chance themselves to study beyond Standard Four. [Photo:KHRG][86]

This photo was taken in July 2002. Students and teachers at a school set up by internally displaced villagers at T--- in Lu Thaw township, Hpapun District. Whenever the villagers hear an approaching Tatmadaw column, they must close the school and flee deeper into the mountains. [Photo: KHRG][87]

This photo was taken on December 31st 2014. It show a temporary teaching place in A’pa Lon village, Win Yin Township, Dooplaya District, which is under a monastery as there is no school in this village. In total there are 65 students from Kindergarten to Sixth Standard. The students are divided into two groups to be taught as they don’t have enough space for more classes. One group is taught under the monastery, the other group of students is taught outside. [Photo: KHRG][88]

13 years old Naw A--- and her younger sister, 11 years old Naw M---, are shown here on November 17th 2008 helping their family by pounding paddy to remove the husks at their home in Thaton District. Naw A--- is the eldest daughter in the family and currently attends third standard. After finishing school, in the evening both girls regularly help their parents with work around the house. Livelihood needs significantly affect the amount of time that many children have for their education. [Photo: KHRG][89]

13 years old Saw E--- is shown here on July 25th 2008 at his family’s farm field in Bilin Township, Thaton District, marching a buffalo around to break up the soil in preparation for planting paddy. Although Saw E--- is only 13 years old, he cannot currently attend school because his parents cannot afford the school fees and need him to work and contribute to the household income. Saw E--- has therefore had to work for his parents and also engage in wage labour tending to other people’s buffalo and cattle. [Photo: KHRG][90]

In April 2006, Tatmadaw Light Infantry Battalion #349 forcibly relocated the residents of numerous villages in Nyaunglebin District to Htaik Htoo relocation site, which is also located in Nyaunglebin District. Over nearly three years, the empty homes and other buildings in the formerly occupied villages became dilapidated. However, in December 2008, the former residents of B--- village, one of those that had been previously relocated, were able to return to their homes and have since rebuilt the local school, as shown in the photo, although without any Myanmar government assistance. [Photo: KHRG][91]

This photo taken in 2005 shows Naw R---, aged 17, who is a schoolteacher in Hpapun district. Naw R--- lives in a house the villagers built for her, where she raises chickens as a way to get money to go home during the school holidays. On August 28th 2005, Tatmadaw troops from Light Infantry Division #44, Infantry Battalion #207 Column 2, came and stayed a night in the village, and the next morning they stole four of her chickens. She says she didn’t dare complain for fear of retaliation. [Photo: KHRG][92]

This photo taken in 2004 shows students from S--- village’s middle school in Toungoo District studying. On December 18th 2004, a column from Tatmadaw LIB #590 (commanded by Battalion Commander Ko Ko Oo), based in Tha Aye Hta, marched through several villages in the area, so the villagers fled to the forest around B--- area. Local schoolteachers planned and discussed how they could teach in hiding in the forest. Middle school students here are preparing their lessons. Continuing school activities is one way that Karen displaced people retain their dignity and community while on the move. [Photo: KHRG][93]

Footnotes:

[1] “INTERVIEWS ON THE SCHOOL SITUATION,” KHRG, June 1996.

[2] “Mergui-Tavoy Situation Update: Ler Doh Soh Township, June to November 2015,” KHRG, July 2016.

[3] According to Myanmar’s Ministry of Education (MoE), expenditure on education has been increased from 0.7% of GDP in Financial Year (FY) 2010-2011 to 2.1% of GDP in FY 2013-2014. For more information see: “National EFA Review Report,” MoE, March 2014.

[4] According to the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS), there were 284,278 young children not enrolled in school across Myanmar in 2014, compared with 649,341 in 2010. For more information, see: Myanmar profile, UNESCO.

[5] “Hpapun Interview: Saw A---, January 2014,” KHRG, April 2015.

[6] “Constitution of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar,” Myanmar Ministry of Information, 2008.

[7] “National Education Law,” Union Parliament of Myanmar, Parliamentary Law No. 41, September 2014.

[8] “National Education Amendment Law,” Union Parliament of Myanmar, Parliamentary Law No. 38, September 2015, (Burmese language only).

[9] “National Education Strategic Plan 2016-21,” The Government of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar, Ministry of Education, February 2017.

[10] “Dooplaya Situation Update: Kyainseikgyi Township, December 2014,” KHRG, June 2015.

[11] Tatmadaw refers to the Myanmar military throughout KHRG’s 25 years reporting period. The Myanmar military were commonly referred to by villagers in KHRG research areas as SLORC (State Law and Order Restoration Council) between 1988 to 1997 and SPDC (State Peace and Development Council) from 1998 to 2011, which were the Tatmadaw-proclaimed names of the military government of Myanmar. Villagers also refer to Tatmadaw in some cases as simply “Burmese” or “Burmese soldiers”.

[12] “SLORC SHOOTINGS & ARRESTS OF REFUGEES,” KHRG, January 1995.

[13] “STARVING THEM OUT: Forced Relocations, Killings and the Systematic Starvation of Villagers in Dooplaya District,” KHRG, March 2000.

[14] “PEACE VILLAGES AND HIDING VILLAGES: Roads, Relocations, and the Campaign for Control in Toungoo District,” KHRG, October 2000.

[15] “[T]hey [SLORC/Tatmadaw] come to the village and give the villagers big problems. So the villagers have to teach their children secretly. The SLORC has a school close to the town, and they say that any villager who wants their children to go to school must send them to this school and no other. But the villagers can’t, because it’s too far. To get there takes a 7 hours walk, from early morning till noon.” “SLORC ABUSES IN HLAING BWE AREA,” KHRG, March 1994.

[16] “UNCERTAINTY, FEAR AND FLIGHT: The Current Human Rights Situation in Eastern Pa’an District,” KHRG, November 1998.

[17] “Toungoo District: The civilian response to human rights violations,” KHRG, August 2006.

[18] “Burma Army attacks and civilian displacement in northern Papun District,” KHRG, June 2008.

[19] “Forced Labour, Extortion and Abuses in Papun District,” KHRG, June 2006; for more information see Chapter 5: Looting, Extortion and Arbitrary Taxation.

[20] “FIELD REPORTS: MERGUI-TAVOY DISTRICT,” KHRG, July 1995.

[21] “CAUGHT IN THE MIDDLE,” KHRG, September 1999.

[22] “Hpapun Situation Update: Bu Tho Township, January to June 2014,” KHRG, December 2014.

[23] “Hpapun Situation Update: Lu Thaw Township, March to May 2014,” KHRG, November 2014.

[24] “Dooplaya Situation Update: Kyainseikgyi, Kawkareik and Kyonedoe townships, October 2013 to January 2014,” KHRG, July 2014.

[25] Source #30.

[26] “Hpapun Situation Update: Dwe Lo Township, January to May 2016,” KHRG, September 2016.

[27] “Dooplaya Situation Update: Kyonedoe and Kawkareik townships, July to November 2014,” KHRG, January 2016.

[28] “Thaton Situation Update: Hpa-an Township, January to June 2014,” KHRG, October 2014.

[29] “Toungoo Situation Update: Thandaunggyi Township, June to August 2016,” KHRG, March 2017.

[30] Source #78.

[31] “Dooplaya Situation Update: Kyonedoe and Kawkareik townships, July to November 2014,” KHRG, January 2016.

[32] “Thaton Situation Update: Thaton Township, July to October 2015,” KHRG, April 2016.

[33] “Dooplaya Situation Update: Kyainseikgyi Township, December 2014,” KHRG, June 2015.

[34] “Toungoo Situation Update: Thandaunggyi Township, July to November 2014,” KHRG, April 2015.

[35] “Thaton Situation Update: Thaton Township, April 2014” KHRG, January 2015.

[36] A Standard refers to a grade in the Burmese education system. Primary school runs from Standard 1 to Standard 4, middle school is Standards 5-8 and high school is Standards 9-10.

[37] “Hpapun Situation Update: Dwe Lo Township, August to October 2015,” KHRG, March 2016; see also “Hpapun Situation Update: Dwe Lo Township, February and March 2014,” KHRG, November 2014.

[38] Source #10.

[39] “Hidden Strengths, Hidden Struggles: Women’s testimonies from southeast Myanmar,” KHRG, August 2016.

[40] “The Asia Highway: Planned Eindu to Kawkareik Town road construction threatens villagers’ livelihoods,” KHRG, March 2015; see also “Recent fighting between newly-reformed DKBA and joint forces of BGF and Tatmadaw soldiers led more than six thousand Karen villagers to flee in Hpa-an District, September 2016,” KHRG, December 2016; “Thaton Interview: Ma A---, July 2015,” KHRG, August, 2015.

[41] “Road construction, attacks on displaced communities and the impact on education in northern Papun District,” KHRG, March 2007.

[42] “Road construction, attacks on displaced communities and the impact on education in northern Papun District,” KHRG, March 2007.

[43] “PEACE VILLAGES AND HIDING VILLAGES: Roads, Relocations, and the Campaign for Control in Toungoo District,” KHRG, October 2000.

[44] “PEACE VILLAGES AND HIDING VILLAGES: Roads, Relocations, and the Campaign for Control in Toungoo District,” KHRG, October 2000.

[45] “Continued Militarisation, Killings and Fear in Dooplaya District,” KHRG, June 2005.

[46] “Toungoo Situation Update: Thandaunggyi Township, January to February 2015,” KHRG, October 2005.

[47] “Toungoo Situation Update: Thandaunggyi Township, November 2015 to February 2016,” KHRG, November 2016.

[48] “Dooplaya Situation Update: Win Yaw Township, November to December 2013,” KHRG, July 2014.

[49] “Dooplaya Situation Update: Kyonedoe Township, January to June 2014,” KHRG, September 2014.

[50] “[T]he villagers submitted their case [information about over crowding] to the Burma / Myanmar government inorder toget support, butthe Burma/Myanmar government didnot give them any support. The villagers proposed to the Burma / Myanmar government[that they need to]rebuild the school more than three times. Yet, there wasno reply from the Burma/Myanmar government.”“Toungoo Situation Update: Thandaunggyi Township, November 2015 to February 2016,” KHRG, November 2016.

[51] Although the interviewee calls this fee “tuition,” he is referring to a fee for private, after-school lessons, taught by the school teachers of their own volition. Since the quality of education in the day schools is very poor, it is common for parents who are able to afford after-school lessons to send their children to these properly-taught classes.

[52] “Toungoo Interview: Maung A---, April 2015,” KHRG, January 2016.

[53] “PEACE VILLAGES AND HIDING VILLAGES: Roads, Relocations, and the Campaign for Control in Toungoo District,” KHRG, October 2000.

[54] “Dooplaya Situation Update: Kyonedoe Township, September to December 2013,” KHRG, September 2014.

[55] “On October 22nd 2015, Hpapun High School Education Administrator U Pa Thaw Khel’s son Saw Tha Hay Bluh, who is teaching in Baw Hta Primary School, beat the students who did not pass their monthly exams. He beat them on their heads, thighs and calves. We saw that the calves and thighs of the students were bruised and some students were not able to go to school [after having been beaten by the teacher].” “Hpapun Situation Update: Bu Tho Township, June to October 2015,” KHRG, February 2016.

[56] Source #62.

[57] “Insomevillages, somepeoplesaidthatBurmesefemale teachersbrutallybeat thechildren[students]if theycouldnotfollow thelessons.” “Dooplaya Situation Update: Win Yay Township, June to July 2015,” KHRG, March 2017.

[58] Source #62.

[59] A term used by ethnic minority groups to describe the assimilation policy implemented by the Burmese government to assimilate non-Burman/Bamar ethnic groups into Burman/Bamar.

[60] “STARVING THEM OUT: Forced Relocations, Killings and the Systematic Starvation of Villagers in Dooplaya District,” KHRG, March 2000.

[61] “UNCERTAINTY, FEAR AND FLIGHT: The Current Human Rights Situation in Eastern Pa’an District,” KHRG November 1998.

[62] Source #28.

[63] “STARVING THEM OUT: Forced Relocations, Killings and the Systematic Starvation of Villagers in Dooplaya District,” KHRG, March 2000.

[64] “Mergui-Tavoy Situation Update: Ler Doh Soh Township, June to November 2015,” KHRG, July 2016.

[65] “Toungoo Situation Update: Thandaunggyi Township, June to August 2016,” KHRG, March 2017.

[66] “Nyaunglebin Situation Update: Mone Township, February to August 2016,” KHRG, November 2016.

[67] Source #98.

[68] Source #85.

[69] This is consistent with KHRG’s findings with regard to Myanmar government investments in services and sectors other than education, for more information see Chapter 6: Development.

[70] “Thaton Situation Update: Hpa-an Township, January to June 2014,” KHRG, October 2014.

[71] Source #107.

[72] “Using any opportunity that they get, the teachers try to teach the students the Karen subject and Karen children can write a bit in their language. Because of the [efforts of the] Karen teachers, students get the opportunity to study Karen language in the township office. The education is getting better and the situation has improved compared to before.” “Mergui-Tavoy Situation Update: K’Ser Doh Township, August to October 2015,” KHRG, May 2016.

[73] “In the KNU-controlled area,[the villagers] build self-reliant schools so the children can go to school and they [also] hire teachers to teach.” Source #94.

[74] “[T]hey know that the Burma government doesnot like it, but they [Karen villagers] know the Karen people are asking for equality from the Burma government so they are raising the Karen flag.”“Hpa-an Situation Update: Paingkyon Township, June to October 2014,” KHRG August 2015.

[75] Source #165.

[76] Source #174.

[77] Source #170.

[78] “PHOTO SET 2005-A: Children,” KHRG, May 2005.

[79] “Free-fire Zones in Tenasserim Division,” KHRG, May 1997.

[80] “Enduring Hunger and Repression: Food Scarcity, Internal Displacement,and the Continued Use of Forced Labour in Toungoo District,” KHRG,September 2004.

[81] “PHOTO SET 2002-A,” KHRG, June 2000.

[82] Source #80.

[83] Source #114.

[84] “KHRG Photo Gallery 2009,” KHRG, July 2009.

[85] Source #50.

[86] “PHOTO SET 2005-A: Children,” KHRG, May 2005.

[87] “PHOTO SET 2005-A: Children,” KHRG, May 2005.

[88] Source #54.

[89] “KHRG Photo Gallery 2009,” KHRG, July 2009.

[90] “KHRG Photo Gallery 2009,” KHRG, July 2009.

[91] “KHRG Photo Gallery 2009,” KHRG, July 2009.

[92]“KHRG Photo Gallery: 2005: Education and ‘Development’ Projects,”KHRG, April 2006.

[93] “PHOTO SET 2005-A: Children,” KHRG, May 2005