This Interview with Saw N--- describes the perceptions of the local community about the development of a limestone quarry and cement factory in Min Lwin Mountain, in Thaton District.

- In June 2017, Karen National Union (KNU) Thaton Township leaders held a consultation meeting about the development of a limestone quarry and cement factory. They only invited local leaders from Min Lwin village tract, Thaton Township. During this consultation meeting, they did not provide adequate information about the impact of this factory on the local community. Instead, they distributed assessment survey forms to all local community members. The lack of adequate information led to disagreements among the local community.

- The process of gaining the consent of the local community has been controversial. Households that live far from the Mountain were included in the process, even though they are not directly impacted by the limestone quarry and cement factory. Many households who signed their names did not realise this would constitute consent to the development project. The names of people who have emigrated to Thailand were also found among the signatures of people agreeing to the development of a limestone quarry on Min Lwin Mountain.

- Local people predict that the negative consequences of the limestone quarry on Min Lwin Mountain are the loss of community forest, environmental damage and the loss of biodiversity, farm lands, plantations and potential displacement due to livelihood problems.

Interview | Saw N--- (male, 51), Q--- village, Thaton Township, Thaton District (June 2017)

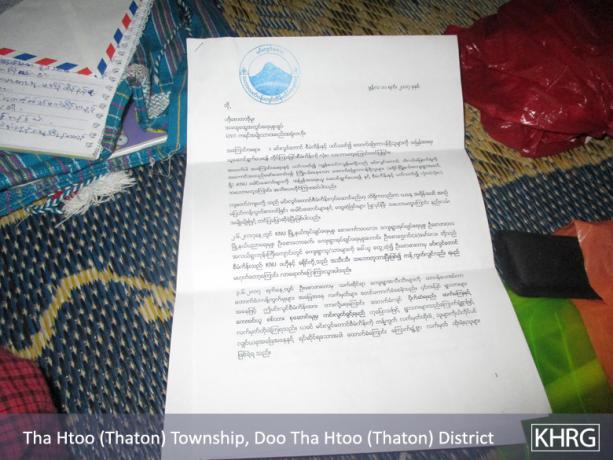

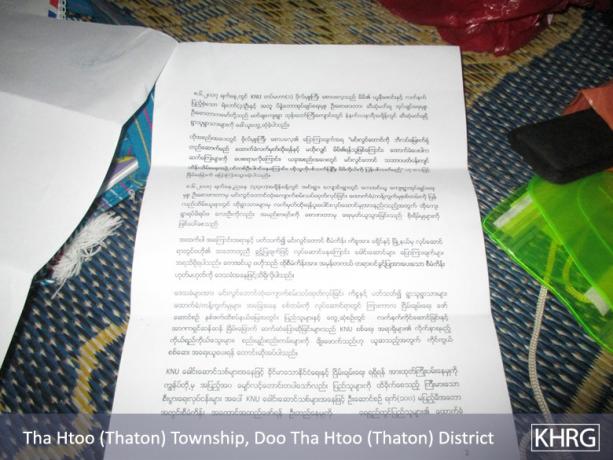

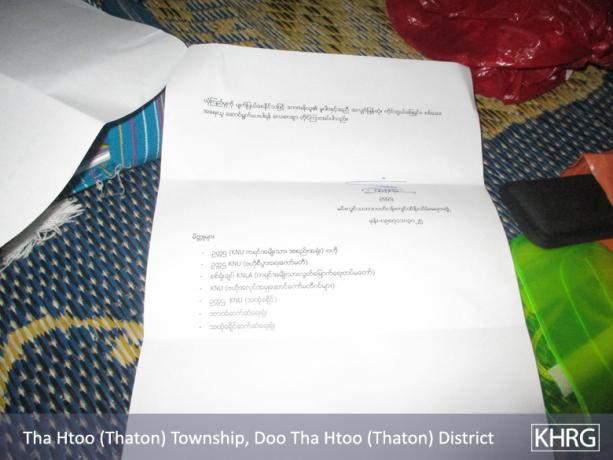

The following Interview was conducted by a community member trained by KHRG to monitor local human rights conditions. It was conducted in Thaton District on June 17th 2017 and is presented below translated exactly as it was received, save for minor edits for clarity and security.[1] This interview was received along with other information from Thaton District, including five other interviews, one situation update and 53 photographs.[2]

Ethnicity: Karen

Religion: Buddhist

Marital Status: Married

Occupation: Farmer

What is your name Dtee?[3]

My name is Saw N---.

How old are you?

I am 51 years old.

What is your marital status?

I am married.

What is your job?

I am a farmer and cultivator.

What responsibilities do you have in your community?

(censored for security reasons)

What is your religion?

I am a Buddhist, but I have good relations with people from all religions in my community.

What is your ethnicity?

I am Karen.

Where do you live?

I live in Q--- village.

What village tract and township?

Maw Lay village tract, Thaton Township [Thaton District].

I would like to interview you about the cement factory that [Pyu Min Htun] company intends to build at Min Lwin mountain. Their survey process started in 2015, correct?

Actually, the [company workers] started their [project activities] in 2014.[4]

I received information that the company will start their project again [in 2017], that they collected the signatures of villagers [through a survey], in order to gain the consent of the population and start their project. Do you have any information about this?

They said that they would start conducting a survey in June [2017]. The new [Min Lwin] village tract administrator said that if a majority [more than 50 percent] of civilians consent to the cement factory, then the company can start building it. If the number [of people who vote for the project] falls short of a majority, the company will be unable to proceed further.

Unfortunately, the number of people who will be surveyed does not correspond to the population that will be negatively impacted by the cement factory. There are more villagers who live far from the [Min Lwin] mountain than villagers who live close to the mountain. [For example], if there are around 100 households near the mountain, there are more than 400 households in the area far from the mountain, including P’Nweh Kla big village. If the company starts building its cement factory [and to quarry limestone], only the villagers who live close to the mountain will face its negative impacts.

I did not say anything in regards to the project; [the company] will do whatever they want to do, but I am supporting the civilians. The villagers who live close to the rocky mountain did not give consent for the limestone quarry and cement factory project. I told the village tract administrator, “If you think [the company] will build the [cement factory], you can make an agreement with them.” I am used to working with the environmental conservation [committee to stop the project] so I will continue to work with them.

When did the [company] conduct the survey?

On June 2nd 2017 in the morning, KNU Township level administrators held a consultation meeting with village elders, village leaders and village tract leaders in P’Nweh Klah monastery. They held another meeting in Ka Da Nay monastery at around 2 PM [on the same day]. Around 20 people attended this meeting, including some [KNU] Township administration staff, village elders, former and current village leaders, and some village tract leaders. In the meeting, they were talking about the decision of KNU authorities to authorise the testing of the limestone in the area.[5] District #1 [Thaton] and Township level administrators wanted this factory to be built in their area.

The following day, on [KNU] distributed survey forms to all sections and villages in the Min Lwin village tract community, including La Hkoh, P’Nweh Kla, Ka Da Nee and others villages. At first, community members from T’Kwee Kla village and other villages refused to give their consent. They said that they did not understand what the survey entailed, and what would happen to them if they did not sign the survey. They did not know how the cement factory would impact them in the future so they refused to sign.

[Local people asked] the Burma/Myanmar government village and village tract administrators [about this survey] and they replied, “We won’t hand the [survey record list] paper to the company directly. We will keep it [the survey forms] with us first, then we will ask the perspective of the KNU village tract administrator and then we will send it to the company.”

On June 8th 2017, the KNU [Thaton] District administrator held another meeting with some villages elders, leaders and village tract leaders in P’Nweh Kla Th’ Waw Thaw village. About six people attended the meeting this time. During the meeting, the Burma/Myanmar government village tract administrator asked the KNU [Thaton] District administrator, “Pu, if you give the Min Lwin mountain to the company and then if the [cement factory] project destroy the civilians’ plain farms around the rocky mountain, how will you do [solve] this problem?”

The KNU [Thaton] District administrator replied, “You don’t have to worry about anything. It will be resolved [because] KNU and local villages elder will take responsibility for this issue.” This is the information that I received from the people [who attended the meeting]. According to my opinion, the KNU [Thaton] District administrator is too casual regarding the issue. [He does not understand the severity of the problem], there are around 1,000 villagers living around the rocky mountain. I do not think that the KNU and village elders can handle this case effectively.

Who held the consultation meeting in P’Nweh Kla village monastery and when?

The KNU township administrator, secretary and treasurer held a consultation meeting on June 2nd 2017 by the order of KNU [Thaton] District chairman.

Who do you think distributed the survey to villagers?

I think, the people who distributed the paper [survey] were not [Pyu Min Htun] company staff because the formal Burma/Myanmar government village head called the company staff on the day the survey was distributed to the villagers. When he asked them about the survey, they replied, “We do not know anything regarding to [the survey] process. It is in the KNU’s hands.” So, local villagers could not do anything.

What is the perspective of villagers according to [the cement factory project] survey?

Mostly, villagers do not understand the cement factory [project]. They are doubtful about the information they have received, and do not know if it is correct. The survey process is not just or transparent because [the KNU] did not provide clear information or explain the process to the villagers. As a result, some villagers did not know what signing the survey would entail. [They did not realise that signing their names would mean providing consent]. In eastern P’Nweh Kla village, [the KNU] collected [a list of name of] all the people who had migrated to Bangkok, Thailand [as being in agreement with the project] without getting their signatures.

They did this in order to ensure that they would have the signatures of the majority of the villagers, which would enable them to start the project.

If they provided clear and detailed information about the [the potential impacts of the cement factory] to the local community, how do you think people would react?

I think that the only villagers who would accept the [cement factory] project are people who have businesses, cars or trucks. But most villagers who live close to the [proposed limestone quarry and cement factory sites] would not give their consent. When the company conducted a survey for the first time, the results showed that most villagers opposed the [cement factory].

Then, they asked village and village tract leaders to conduct the survey, but people did not participate in it. So the [Pyu Min Htun company] handed it to government workers. At this time, they [government workers] told villagers,

“If you sign your name [and provide consent to the limestone quarry and cement factory], you will get money and you will not have to pay any taxes. If you do not sign your name, the company will conduct the project anyway because the KNU authorities already gave permission.”

As result, villagers were frightened. Therefore, they signed their name [in approval of the project, even though they did not agree to the project]. The [company] received a lot of support from the civilians this time, including from the villagers from Taw Thoo Klah, Lah Hko and Maw Kloe villages. [The villagers provided their consent] KNU would not do these things in the past [give tax concession for approving the project], this goes against KNU policy.

How many villages did the [KNU] approach throughout their survey processfor the [cement factory] project?

They [KNU] surveyed all villages located around the [Min Lwin] Mountain, from Htee Poe Htoo and Noh Poe Hta villages to Lah Hkoe villages.

Actually, they surveyed a lot of the villages that are far from the [Min Lwin] Mountain, including from people whose lands would not be directly impacted by the development of the limestone quarry and cement factory. The KNU village head of Lah Hkoe also tried to entice the villagers in order [to help] the [company] get the necessary majority. By doing so, the [KNU] got the required majority.

What villages are situated closest to the Min Lwin rocky Mountain?

Maw Lay, Noh Hote Day, Noh Pler Plu, Htee Nya Loo, T’La Aww Poe Kla and other villages are surrounding the mountain.

Can you describe the differences in opinion between the villagers who live close to the mountain and those who live further away?

There are only ten people in Noh Htoe Day, a village close to the [Min Lwin] Mountain who gave consent for the [cement factory]. A large number of people from other villages that are close to the mountain did not consent to the project. There are some people from Noh Htoe Day who also told me that they did not understand the consequences of signing the survey document, or [that they did not have enough information about the development of a limestone quarry and] cement factory. Thus, they said,

“We signed it just because people [from the community] asked us to sign.”

Some villagers and Tharamu Tha Da Aye who cooperated with the Min Lwin Mountain environment conservation committee also argued with the [KNU] staff who conducted the survey [about the way the survey was conducted]. Tharamu and I did not sign our names on their paper.

What is the opinion of the people who live far away from the mountain regarding the [proposed cement factory] project?

The people who live far from the mountain approve of the cement factory. Many of them live around five to eight furlongs [201 meters] away from the mountain.

In your opinion, if the company constructs the cement factory, what are the negative consequences that local villagers will face?

I think the project will cause damage to the farmlands of local villagers, and damage to the mountain [forest]. I think some villagers might be displaced to other areas. The biodiversity of the mountain: all animals, trees, water source and herbal medicine will be destroyed. There is a spring in the [mountain’s] forest that produces water for animals and people in summer.

Our elders also have a poem about the pond on Min Lwin Mountain. The pond has been there since the queen [ruled this area in ancient times]. Min Lwin Mountain is the most important and biggest mountain to this community. Htee Nya Lu hill is smaller than the Min Lwin Mountain. There are all kinds of animals on the mountain, including deer, bears, monkeys and others.

What are the other possible negative impacts on the local community?

If the cement factory is built starting [tomorrow], we would have to flee to other places. The limestone mine and cement factory may possibly destroy the nearby villages. How can we feel safe staying here? If the cement factory is constructed in this area, there will be many other negative impacts on villagers.

Currently, local villagers do not have access to clear and detailed information about the development of the cement factory project, which is causing arguments and tension in the community. We have to be aware of [the importance of] our community relations. If [the company] stops the project, the villagers will no longer worry.

Currently, when we go to other villages like Maw Lay or P’Nweh Klaw, villagers are no longer friendly with us. Most people who live far from the mountain want the cement factory to be built. Those who live close to the mountain oppose the cement factory because their land will be destroyed and damaged. The company should prioritise the [opinions of] people who live close to the mountain. Community members who live far from the mountain should take pity on them because we are all part of the Karen ethnic group. If not, the people who live close [to the mountain] will be in trouble.

Can we [KHRG] use the information about the [cement factory project at] Min Lwin Mountain that you provided me with for publication?

Yes, you can use this information for publication because I have told the truth about the incident. I do not mean to insult my people. I reported what our [KNU] leaders had done and the true position of the villagers [and their concerns]. We just want the mountain to stay like this [forever] because it has been like this since our ancestors [lived here]. This is the most beautiful and the largest mountain in Thaton Township. There are many monastery buildings and pagodas that are situated beside the road so everyone can come and attend their services. Therefore, the company should not destroy the mountain.

What is the company name?

People call it the Pyu Min Htun Company.

What are the names of the people who are leading the company?

The company name is Pyu Min Htun. The owner’s name is U Thin Htun. There were three managers. The current manager is U Zaw Lwin. He lives in Min Lwin village tract.

Thank you for providing information and allow us [KHRG] to use your information. May you be healthy.

Thank you.

Footnotes:

[1] KHRG trains community members in southeastern Burma/Myanmar to document individual human rights abuses using a standardised reporting format; conduct interviews with other villagers; and write general updates on the situation in areas with which they are familiar. When conducting interviews, community members are trained to use loose question guidelines, but also to encourage interviewees to speak freely about recent events, raise issues that they consider to be important and share their opinions or perspectives on abuse and other local dynamics.

[2] In order to increase the transparency of KHRG methodology and more directly communicate the experiences and perspectives of villagers in southeastern Burma/Myanmar, KHRG aims to make all field information received available on the KHRG website once it has been processed and translated, subject only to security considerations. For additional reports categorised by Type, Issue, Location and Year, please see the Related Readings component following each report on KHRG’s website.

[3] Dtee is a familiar term of respect in S’gaw Karen attributed to an older man that translates to “uncle,” but it does not necessarily signify any actual familial relationship.

[4] For more information regarding the Maw Lay Cliff (also known as Min Lwin mountain) stone mining for cement project see “Thaton Situation Update: Thaton Township, January to June 2015”, KHRG, January 2016, “Thaton Field Report: January to December 2015,” KHRG, August 2016, and “Thaton Interview: U A---, 2016,” KHRG, May 2016.

[5] Even though the KNU central authority had officially suspended the feasibility study for the cement factory being carried out by the Phyu Min Tun Company near Min Lwin Mountain, local authorities continued to meet with villagers, as confirmed by the following articles:"KNU Suspends Min Lwin Mountain Cement Factory Project," BNI Multimedia Group, April 2016 and "Residents Call on KNU to Scrap Contentious Cement Factory Plans," KIC, June 2017.