This Field Report includes information submitted by KHRG researchers describing events occurring in Thaton District between September 2012 and December 2013. The report describes human rights violations including sexual assault, land confiscation, arbitrary taxation and demands, forced labour and forced recruitment into a government militia. It also documents villagers’ reactions to the ongoing ceasefire process and resulting changes in the military situation in Thaton District, as well as the consequences of gold mining and an increase in activities related to education and healthcare by NGOs, the government, the KNU and cross border groups.

Field Report: Thaton District, September 2012 to December 2013

Land confiscation

Since the ceasefire,[1] many local companies and wealthy business people have come to Thaton District and established rubber plantations on land that villagers were forced to sell. The Burma/Myanmar government has granted permission to some of these individuals to use the land without negotiating with local communities or the owners of the land. Therefore, some villagers from S--- village, T--- Baw village and H--- village reported the problem to the KNU in order to try and get their land back. In response, KNU officials met with the wealthy people to resolve the issue.[2] After the meeting, the wealthy people agreed to give back the land, but demanded that the villagers redeem their land for 50,000 kyat (US $48.83)[3] per acre. Villagers who did not have the money had to forfeit their land.

Gold mining projects

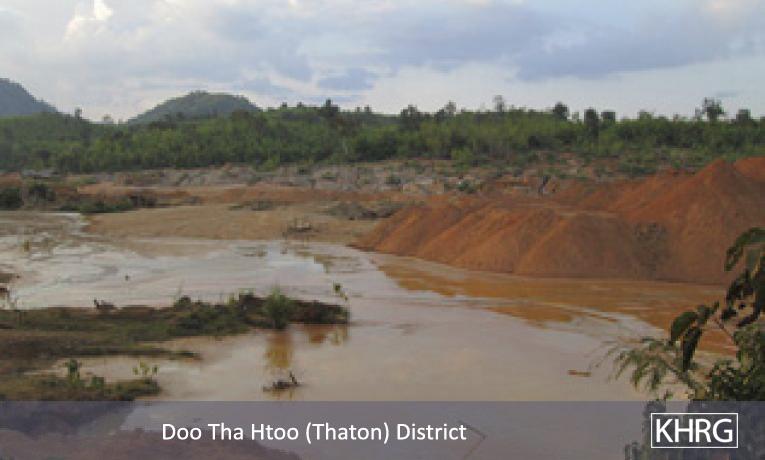

Villagers also raised there concerns regarding a gold mining project involving the KNU.[4] On February 4th 2013, KNU officials gave permission to a local company, KoCho/Maung Muang Yi, to conduct gold mining in Ee Hkoo Hkee and P’Da Daw village tracts in Bilin Township. The company was given permission to work on the project for six months. The gold mining project damaged local villagers’ agricultural plots and the surrounding natural environment.

Sexual Assault

On September 27th 2013, a soldier from Light Infantry Battalion (LIB)[5] #558 led by Battalion Commander Than Htet Oo, which is under Military Operations Command (MOC)[6] #13 from P’Nwe Klah, attempted to rape a villager after the battalion had entered D--- village some two weeks earlier. The soldier attempted to rape Naw B--- during the night after entering her house without permission, but he was prevented from doing so when she shouted for help. The village head went to report the case to the battalion commander, but the battalion commander was away, and the Tatmadaw official who was in the camp told the village head not to report it and asked what they could do to satisfy Naw B---. Naw B--- asked the village head to tell the battalion commander to ensure that the soldier would not come to her home again. The case ended there.[7]

Tatmadaw and government activities

Villagers have reported that since the ceasefire, the Burma/Myanmar government has increased the reach of its administration, which now has a presence in almost every village tract and township in Thaton District. The administrative structures at the village tract level include three people: a village tract administrator, a secretary and an accountant. The Burma/Myanmar government provides a salary to the village tract administrator, but not to the secretary or accountant. Additionally, the government has also appointed a leader for every ten households and one leader for every 100 households in this area. The villagers believe this is a strategy of the Burma/Myanmar government to collect more votes in the 2015 election.[8]

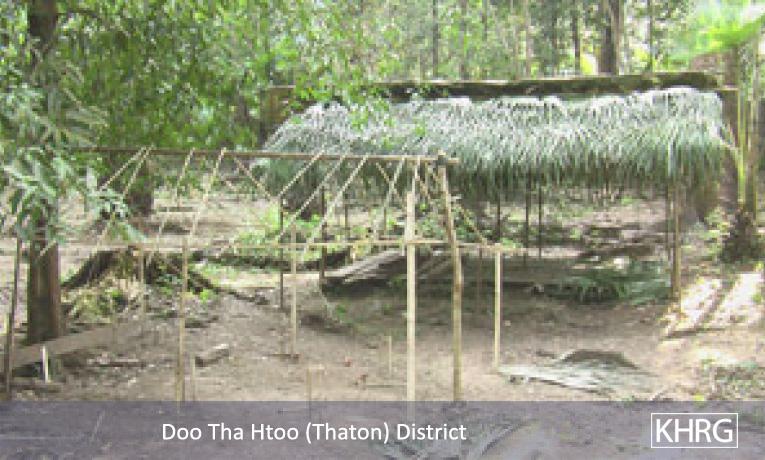

On October 9th 2013, LIB #559 led by Battalion Commander Thein Htike Oo rotated and replaced LIB #558 in P’Nweh Klah army camp. This new military group has become more active than others. LIB #559 was staying in T’Maw Daw on October 10th 2013. They then travelled to Noh Per Baw village and on October 13th and 14th 2013, they built a temporary camp above the Noh Per Baw monastery. On October 20th 2013, they returned to T’Maw Daw and stayed in the T’Maw Daw monastery compound until the end of the month. The constant presence of LIB #559 in the village has caused difficulties for local villagers who search for food during the night, as restrictions have been placed on their movements. KNU leaders said that although the Tatmadaw have agreed to the ceasefire, the Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA) does not trust them anymore and the villagers are also worried that armed conflict may erupt again because of their constant presence in the area.[9]

Border Guard Force

On September 15th 2013 Border Guard Force (BGF)[10] Battalion #1014 established a new camp in Koh Tah Kyee village, T’Kaw Boh village tract, Hpa-an Township. There are three BGF army camps based in Hpa-an Township: Law Poo, Meh Poo and Koh Tah Kyee. Local villagers do not know why the BGF has set up another camp.

Forced recruitment

On September 21st 2013, pyithu sit (people’s militia)[11] member Maung B--- reported to a KHRG researcher that on the previous day, villagers serving in the militia from Kyauk Lon Kyi village tract, Kyaikto Township had to renew their militia membership cards with the Tatmadaw, extending their service time in the pyithu sit. Local villagers told a KHRG researcher that following the ceasefire, they no longer wanted to serve in the militia as it prevented them from sustaining their livelihoods. Villagers from Kyauk Lon Kyi village tract, which includes L---, M---, N--- and P--- villages, were given a total of 16 guns in order to serve in the pyithu sit when they were originally recruited in 1988. In September 2013, they tried to return their guns and leave the militia, but the Tatmadaw accepted only eight of the guns, and the villagers had to pay 25,000 kyat (US $24.41) to Tatmadaw Infantry Battalion (IB)[12] #8 for each gun returned. The villagers later tried again to return the remaining guns, but the Tatmadaw refused to accept them, even though the villagers offered to pay IB #8 50,000 kyat (US $48.83) to return each of the remaining guns.[13]

Forced labour, looting and demands

According to information from KHRG researchers between February and August 2013, forced labour remained ongoing in Thaton District. The most commonly reported perpetrators were Tatmadaw LIB #561 and BGF Battalion #1014. However, forced labour demands had stopped in six villages in Bilin Township.

In the first incident, Tatmadaw LIB #561, based at Yoh Klah military camp and led by Commander Naing Lin and Camp Commander Zay Ya Hpoe Aung, took wood belonging to local villagers without their permission in order to rebuild their army camp. This army unit also demanded 100 shingles of thatch from three motor driven wood saw owners, H---, P--- and G--- from Y--- village.[14]

In March 2013, BGF Battalion #1014, in cooperation with the Shwe Tha Lwin and Hein Naing Win companies, ordered villagers from P---, R---, C---, B---, D---, Y--- and Z--- villages in Meh K’Na Hkee village tract and Weh Pya village tract, Hpa-an Township, to clear vegetation in rubber plantations that they had planted in 2012. The villagers have been ordered to do this work regularly since 2012. The two companies paid villagers who did the work 2,000 kyat(US $1.95)per day, but if villagers did not do the work, they had to pay 2,000 kyat to the BGF.[15]

On August 25th 2013, Warrant Officer Eh K’Luh of BGF Battalion #1014, based in Meh Poo army camp, demanded 30 bamboo poles and 17 logs from M--- village in order to repair the battalion’s camp. Villagers did not receive payment for this work but they did not dare to refuse the demand.However,villagers in the area said forced labour had decreased since the ceasefire was signed between the KNU and the Burma/Myanmar government.[16]

On April 29th 2013, a KHRG community member from Bilin Township reported that the demands for forced labour from Lay Kay army camp had ceased and shared the villagers’ views regarding what had brought about this change:

"After we submitted forced labour information to the International Labour Organization (ILO) in July 2012, forced labour happened only one time, when the Tatmadaw ordered D--- villagers to provide thatch for repairing their camp in September 2012. Since then [September 2012], forced labour has not happened again up until now. Based on villagers’ views, forced labour has stopped because of three possible reasons: (1) forced [labour] has stopped after we submitted the forced labour incident to ILO; (2) forced labour has stopped after the KNU and Burma government signed the ceasefire agreement; and (3) forced labour has stopped for the reason that Burmese soldiers now dare to go and cut down trees and bamboo from the forest by themselves [because soldiers are no longer afraid of possible KNLA ambushes].”

Situation Update written by a KHRG researcher in Bilin Township, Thaton District

(Written in April 2013)[17]

Health and Education

KHRG researchers documented positive developments related to health and education in Thaton District since the ceasefire, reporting that new schools, clinics and other humanitarian support had been provided by the government, local non-governmental organizations (NGOs), international NGOs (INGOs), companies, private individuals and other organisations including the KNU’s Karen Education Department (KED), the Karen State Education Assistance Group (KSEAG), the Backpack Health Worker Team (BPHWT), the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) and the INGO World Concern.[18] World Concern has also provided farm loans and microfinance services. All of these organisations, except KSEAG, were operating with the permission of the Burma/Myanmar government.

Villages in Thaton District typically have schools that provide instruction until the 4th standard, approximately age 10 or 11, most of which were established by the villagers themselves, because in many areas, neither the Burma/Myanmar government nor the KNU provide support for the establishment of schools. Many children quit school to begin working after the 4th standard. To continue their studies, students typically have to travel to a city, which most parents cannot afford. For this reason, very few students continue through to the 10th standard to graduate from secondary school.[19]

KHRG received reports that two companies had built health or educational facilities in Thaton District in 2013. The Max Myanmar Company,[20] after receiving permission from the KNU, built primary schools and clinics in Thaton and Hpa-an Townships. In the second reported instance, the Zin Yaung Htun Taung Company built a clinic in Ee Heh village, Hpa-an Township and the company finished construction on February 16th 2013. However, KHRG researchers reported that after the clinic had been built, there were no medicine or health workers to supply the clinic. Villagers do not yet know whether private companies or the government will provide health workers and medicine in the future. The villagers are hopeful that the clinic will provide them with consistent access to medicine. However, because no one has started work in the clinic, villagers are worried that the clinic will not help them.[21]

In March 2013, the well-known Burmese actor Wai Lu Kyaw[22] met with a local KNLA intelligence official to discuss development projects focusing on education, health and electricity in the district. Wai Lu Kyaw wants to support young Karen students from remote, mountainous areas who have graduated from the 10th standard to continue their education for two years or to undergo one year of medical training at a university in Burma/Myanmar, after which they will return to provide support to their local communities. He has also proposed sponsoring students who have completed at least the 4th standard to attend training in the generation of solar power, which would allow them to install solar power units in villages. He proposed that selected students would be given an 80,000 kyat (US $78.12) to 100,000 kyat (US $97.65) stipend. However, implementation of the project has not yet begun.[23]

“…We have seen that the schools became better and there are more schools because the Myanmar government and companies came and started doing the projects. The school materials come from the KED…The assistance is a relief for the parents. And also, UNICEF, which came along through the Myanmar government, also supports the students in primary school, which is related to the government...”

Situation Update written by a KHRG researcher, Hpa-an, Thaton and Bilin townships, Thaton District

(received in July 2013)[24]

In Bilin Township, KHRG researchers reported that the district-level KNU authorities formed an agreement with an unidentified independent organisation to establish schools in 13 villages including, Ta Uh Hkee, Ta Uh Nee, Kyoh Weh Baw Naw Nee, west Yoh Klah, West Htee Hpa Doh Hta, Kyoh Weh, Ler Hpoh, P Ya Raw, Thoo K’Bee, Ler Hklaw, Ta Paw, Ta Paw Hkee and Noh K’Neh villages.[25] The information was announced at a KNU Bilin Township permanent committee meeting on September 18th 2013, though the name of the partner organisation was not made public. KHRG researchers were unable to determine the name of this organisation and villagers reported that they had yet to see any evidence of the organisation after the agreement was made. Villagers also raised concerns regarding instances where teachers in government schools were absent for prolonged periods, making it impossible for the students to attend school regularly.

In Kyaikto Township, healthcare is provided by INGOs and untrained traditional midwives in rural areas. Specifically, villagers reported that since the ceasefire, UNICEF have been able to come to Kyaikto Township and distribute medicine and give vaccinations to children. However, villagers reported that these organisations have not visited their communities regularly.

On September 18th 2013, Burma/Myanmar government health workers provided an elephantiasis vaccination to villagers in Kyaikto Township. They did not conduct diagnoses before letting the villagers take the medicine. Some of the villagers who took the medicine suffered side effects such as urinary retention and swelling of the scrotum, although they recovered after one week. Some of the villagers were frightened and said that they would not dare to take the medicine if Burma/Myanmar government health workers came to give it to them again.[26]

“If we look at the healthcare situation for this township [Thaton], there are many needs. In some villages, the government came and set up clinics but after they set up the clinics, as there are no medics or medicine, they mostly became sleeping places for goats. We also see that there is only one Backpack [BPHWT] clinic in the whole township and they cannot travel to every place.”

Situation Update written by a KHRG researcher, Thaton Township, Thaton District

(Written July to November 2013)[27]

These photos were taken on January 31st 2013 in Woh K’Teh village, Aye Kyoo Hkee village tract, Bilin Township. They show a gold mining operation in Bilin Township and depict the environmental damage and river pollution that such projects may create. [Photos: KHRG]

These photos were taken on October 20th 2013 in Noh Per Baw village, T’Maw Daw village tract, Thaton Township, Thaton District. They show an abandoned temporary camp that had been built above the Noh Per Baw monastery by Tatmadaw LIB #559, led by Battalion Commander Thein Htike Oo. [Photos: KHRG]

These photos were taken on August 1st 2013, and show a clinic under construction, funded by the UNDP in Kon Tan Kyi village, T’Kaw Boh village tract, Hpa-an Township. [Photos: KHRG]

Footnotes:

[1] On January 12th 2012, a preliminary ceasefire agreement was signed between the KNU and Burma/Myanmar government in Hpa-an. Negotiations for a longer-term peace plan are still under way. For updates on the peace process, see the KNU Stakeholder webpage on the Myanmar Peace Monitor website. For KHRG's analysis of changes in human rights conditions since the ceasefire, see Truce or Transition? Trends in human rights abuse and local response since the 2012 ceasefire, KHRG, May 2014.

[2] See “Thaton Situation Update: Hpa-an, Thaton and Bilin townships, January to July 2013,” KHRG, December 2013.

[3] All conversion estimates for the kyat in this report are based on the November 14th 2014 official market rate of 1024.03 kyat to the US $1.

[4] See “Thaton Situation Update: Hpa-an, Thaton and Bilin townships, January to July 2013,” KHRG, December 2013.

[5] Light Infantry Battalion (Tatmadaw) comprised of 500 soldiers. However, most Light Infantry Battalions in the Tatmadaw are under-strength with less than 200 soldiers. Primarily for offensive operations but sometimes used for garrison duties.

[6] Military Operations Command. Comprised of ten battalions for offensive operations. Most MOCs have three Tactical Operations Commands (TOCs), made up of three battalions each.

[7] This information was included in the previously published report “Thaton Incident Report: Attempted rape in Thaton Township, September 2013,” KHRG, August 2014.

[8] See “Thaton Situation Update: Hpa-an, Thaton and Bilin townships, January to July 2013,” KHRG, December 2013.

[9] This information was included in an unpublished report from Thaton District received by KHRG in 2013.

[10] Border Guard Force (BGF) battalions of the Tatmadaw were established in 2010, and they are composed mostly of soldiers from former non-state armed groups, such as older constellations of the DKBA, which have formalised ceasefire agreements with the Burmese government and agreed to transform into battalions within the Tatmadaw. BGF battalions are assigned four digit battalion numbers, whereas regular Tatmadaw infantry battalions are assigned two digit battalion numbers and light infantry battalions are identified by two or three-digit battalion numbers. For more information, see “DKBA officially becomes Border Guard Force” Democratic Voice of Burma, August 2010, and, “Exploitation and recruitment under the DKBA in Pa’an District,” KHRG, June 2009.

[11] Pyithu sit translates to ‘people’s militia,’ which is a militia structure into which local civilians are conscripted to serve in village or town militia groups. For further reading on the pyithu sit, see “Enduring Hunger and Repression; Food Scarcity, Internal Displacement, and the Continued Use of Forced Labor in Toungoo District,” KHRG, September 2004.

[12] Infantry Battalion (Tatmadaw) comprised of 500 soldiers. However, most Infantry Battalions in the Tatmadaw are under-strength with less than 200 soldiers. Primarily for garrison duty but sometimes used in offensive operations.

[13] This information was included in the previously published report “Ongoing forced recruitment into the People’s Militia in Kyeikto Township, Thaton District,” KHRG, January 2014.

[14] This information was included in an unpublished report from Thaton District received by KHRG in April 2013.

[15] See “Thaton Situation Update: Hpa-an, Thaton and Bilin townships, January to July 2013,” KHRG, December 2013.

[16] This information was included in an unpublished report from Thaton District received by KHRG in November 2013.

[17] See “Persistent forced labour demands stop in six villages in Bilin Township as of September 2012,” KHRG, July 2013.

[18] This is information was included in “Thaton Situation Update: Hpa-an, Thaton and Bilin townships, January to July 2013,” KHRG, December 2013, as well as an unpublished report from Thaton District that was received by KHRG in November 2013.

[19] This information was included in an unpublished report from Thaton District received by KHRG in November 2013.

[20] For further information on Max Myanmar, see for example: “Land confiscation and the business of human rights abuse in Thaton District,” KHRG, 2009; and Singapore Stymies Myanmar Mogul Zaw Zaw's Bid for Listing, Wall Street Journal, April 29th 2013.

[21] See “Thaton Situation Update: Hpa-an, Thaton and Bilin townships, January to July 2013,” KHRG, December 2013. This information was also included in an unpublished report from Thaton District received by KHRG in November 2013.

[22] Wai Lu Kyaw established a foundation to support education and health in areas affected by ethnic armed conflict in Burma/Myanmar in 2013. For more information, see: “Movie Actor Wai Lu Kyaw Launches Foundation for Edu and Health,” Kamayut Media TV, February 12th 2013.

[23] See “Thaton Situation Update: Hpa-an, Thaton and Bilin townships, January to July 2013,” KHRG, December 2013.

[24] Id.

[25] This information was included in an unpublished report from Thaton District received by KHRG in November 2013.

[26] This information was included in an unpublished report from Thaton District received by KHRG in November 2013.

[27] This information was included in an unpublished report from Thaton District received by KHRG in November 2013.