- Access to healthcare has been a significant concern throughout 25 years of KHRG reporting. Access to healthcare for villagers has been deliberately denied through Tatmadaw’s imposed restrictions on freedom of movement and the trading of medical supplies in the 1990s and 2000s. Since the 2012 ceasefire, barriers in accessing healthcare have changed from conflict-related to infrastructure-dependent, including the lack of adequate roads to rural areas, and the lack of functioning healthcare facilities in rural areas.

- Displaced villagers suffer disproportionately from a lack of access to healthcare and medical supplies when in hiding. Due to severe restrictions on villagers’ movement, sickness, malnutrition and disease are estimated to have killed more people throughout the conflict than the direct violent abuses of Tatmadaw and EAGs.

- When healthcare facilities are available and accessible, patients report that they are frequently understaffed, lack essential medical supplies, and operate unreliable opening hours. Additionally, villagers have raised complaints about the acceptability of healthcare standards, particularly those made recently available since the 2012 preliminary ceasefire. They have experienced disrespectful and discriminatory Myanmar government healthcare staff, lack of information on the side effects of medicine prescribed, and arbitrary denial of treatment.

- The standard of healthcare services, when made available, has been consistently low throughout 25 years of KHRG reports, particularly in rural areas of southeast Myanmar. Villagers have relied on traditional medics and traditional medicines, most especially during conflict and when in hiding, but this dependence continues in areas which are not served by permanent healthcare staff and in areas where medical supplies are not available.

- Significant financial barriers persist with regard to free and equal access to healthcare. The financial consequences of Tatmadaw, BGF and EAG abuses, including financial extortion and a lack of time for villagers to work for their own livelihoods, left many villagers financially insecure and unable to pay for basic medicines. Whilst these abuses have reduced, villagers report that they continue to find healthcare inaccessible due to financial barriers including the cost of travel to hospitals, the cost of medicine, and the unwillingness of some healthcare staff to treat poorer patients.

Chapter 4: Health

Foundation of Fear: 25 years of villagers’ voices from southeast Myanmar

Written and published by Karen Human Rights Group KHRG #2017-01, October 2017

“We dare not go to the government hospital if we have no money. If we don’t take money they don’t give us medicine [If it is serious] we have to try hard to find the money to cure the disease. Mostly we treat things using traditional medicines. My children have never had an injection or vaccination.They called us to go and get vaccinations for our children but we were afraid because people said their children got feversafter the injection.”

Naw Ek---(female, 30), quoted in a report written by a KHRG researcher, El--- village, Mone Township, Nyaunglebin District/eastern Bago Region (published in May 1999)[1]

“They [the Burma/ Myanmar government] just declared the building of the clinics under their name [so they can claim they have worked for the development of the villages]. We know this as they have not yet [provided] enough medics, nurses and medicines. If you question the villagers [living] there, [near] the clinics that they had built, they only say that those [buildings] are not clinics [since they are never open for patients].”

Situation Update written by a KHRG researcher, Thaton Township, Thaton District/northern Mon State (received in January 2016)[2]

Key Findings

- Access to healthcare has been a significant concern throughout 25 years of KHRG reporting. Access to healthcare for villagers has been deliberately denied through Tatmadaw’s imposed restrictions on freedom of movement and the trading of medical supplies in the 1990s and 2000s. Since the 2012 ceasefire, barriers in accessing healthcare have changed from conflict-related to infrastructure-dependent, including the lack of adequate roads to rural areas, and the lack of functioning healthcare facilities in rural areas.

- Displaced villagers suffer disproportionately from a lack of access to healthcare and medical supplies when in hiding. Due to severe restrictions on villagers’ movement, sickness, malnutrition and disease are estimated to have killed more people throughout the conflict than the direct violent abuses of Tatmadaw and EAGs.

- When healthcare facilities are available and accessible, patients report that they are frequently understaffed, lack essential medical supplies, and operate unreliable opening hours. Additionally, villagers have raised complaints about the acceptability of healthcare standards, particularly those made recently available since the 2012 preliminary ceasefire. They have experienced disrespectful and discriminatory Myanmar government healthcare staff, lack of information on the side effects of medicine prescribed, and arbitrary denial of treatment.

- The standard of healthcare services, when made available, has been consistently low throughout 25 years of KHRG reports, particularly in rural areas of southeast Myanmar. Villagers have relied on traditional medics and traditional medicines, most especially during conflict and when in hiding, but this dependence continues in areas which are not served by permanent healthcare staff and in areas where medical supplies are not available.

- Significant financial barriers persist with regard to free and equal access to healthcare. The financial consequences of Tatmadaw, BGF and EAG abuses, including financial extortion and a lack of time for villagers to work for their own livelihoods, left many villagers financially insecure and unable to pay for basic medicines. Whilst these abuses have reduced, villagers report that they continue to find healthcare inaccessible due to financial barriers including the cost of travel to hospitals, the cost of medicine, and the unwillingness of some healthcare staff to treat poorer patients.

Introduction

Based on villagers’ testimony, this healthcare chapter provides an analysis of how villagers’ experiences and perspectives in regards to their health needs have evolved over the past 25 years. Over a quarter of a century, villagers in southeast Myanmar have consistently identified access to and the acceptability of essential healthcare services as one of the biggest challenges they face, despite the changing context. Decades of conflict have severely impacted civilian health in more ways that direct abuse and torture, by prompting displacement and impeding investments and improvements in essential health infrastructure, particularly in rural areas. Since the 2012 preliminary ceasefire, the situation of human rights violations which impact the condition of villagers’ health in KHRG operation areas have improved to a notable extent. However, significant shortfalls in healthcare provision remain and whilst abuses have decreased, the additional health consequences of conflict on livelihood and financial insecurity, vulnerability to disease, lack of basic health awareness, lack of access to a range of medicines and treatments, a shortfall in skilled and qualified healthcare workers, and inadequate medical and transport infrastructure have not decreased. The result is that despite an easing of direct abuses against villagers by Tatmadaw and some EAGs, serious health concerns persist for villagers in southeast Myanmar.

This chapter is structured to review villagers’ concerns and experiences over 25 years with regard to: access to healthcare; the acceptability of healthcare services related to supplies and services; the acceptability of healthcare services related to staff and skills; and the impact of livelihood and financial insecurity on access to healthcare.

Myanmar’s legal and political commitments

The right to health is recognised as a basic human right in the UDHR,[3] the ICESCR,[4] and a political commitment under Myanmar’s 2008 Constitution, Article 367:

“Every citizen shall, in accord with the health policy laid down by the Union, have the right to health care.”[5]

Additionally relevant, protection of the health of civilians in conflict, including the treatment of wounded[6] and the protection of medical facilities and staff,[7] is recognised in both customary international humanitarian law and the First and Fourth Geneva Conventions of 1949.

In addition to international law, villagers explicitly recognise health as an essential right, and necessary for their access to other basic rights, including education and livelihood security:

“Every rightis important but you have to be healthy if you want to gain education.Therefore, the right to education can [only] come after the right to health care.Things are like that. You must be healthy ifyou want to study. Ifyouare healthy, youcan work toearna living. To be able to earn a living, you need to [also] have freedom of movement and the right to work. Thus, [if you have these] there is no barrier to block your rights. As a human, we have to use our rights in an appropriate way. Nobody should disturb [take away] our rights. We have to take our rights fully [not one right without another] and we have to do our best. If we can work, we can get [enough] food. If we get food, we are healthy. As long as we are healthy, we can study. If we can study, we will be educated. If we are educated, we can improve our community.

Naw Ew--- (female, 24), Ex---- village, Khel Ken Koh village tract, Kyaukkyi Township, Nyaunglebin District/eastern Bago Region (interview received in December 2016)[8]

Access to healthcare: attacks and restrictions

Decades of prolonged conflict in southeast Myanmar have intertwined with the systematic abuses of armed actors against civilians and caused, amongst other concerns, deliberate and debilitating attacks on villagers’ access to healthcare. Particularly in the late 1990s and early 2000s, medical facilities which were often established and run by the local community with KNU or CBO support, were targeted or destroyed by the Tatmadaw[9] as part of their aggressive ‘Four Cuts’ policy.[10] For example, one photo caption written by a KHRG community member from Hpapun District in 2002 shows:

“[This photo shows] There mains of a clinic built by the KNU at Oo Da Hta near the Salween River in Hpapun District. The clinic was built to provide medicine and some measure of healthcare to villagers in the area. The clinic was only temporary because of the possibility of SPDC [Tatmadaw] troops moving into the area. The SPDC came and burned it in early May 2002 at the same time that they burned Kho Kay village.”

Photo Note written by a KHRG researcher, Hpapun District/ northeastern Kayin State (published in December 2002)[11]

Attacks on healthcare facilities continued as Tatmadaw sought to drive villagers out of certain areas, directly blocking their access to healthcare. These were not isolated attacks but part of Tatmadaw strategy to crush any forms of community reliance, evident through almost 20 years of KHRG reports, prior to 2012. Where emergency healthcare facilities were provided, such as by Back Pack Health Worker Team (BPHWT) and Free Burma Rangers (FBR), they were also at risk of being attacked, as was the case when Tatmadaw shelled one IDP site in Ma No Roh village tract, Tanintharyi Township, Mergui-Tavoy District in January 2011 whilst BPHWT were providing emergency medical care to the displaced villagers, evidenced in the testimony of a BPHWT medic:

“It happened when I was staying at P--- village [IDP hiding site] and looking after patients. The SPDC Army [Tatmadaw] Soldiers came and fired mortars at the place we stayed. At that time, during the mortar attack, we all ran up to the mountain, including the children.”

Saw Ep--- (BPHWT) (male, 30), P--- village, Tanintharyi Township, Mergui-Tavoy District/Tanintharyi Region (published in September 2011)[12]

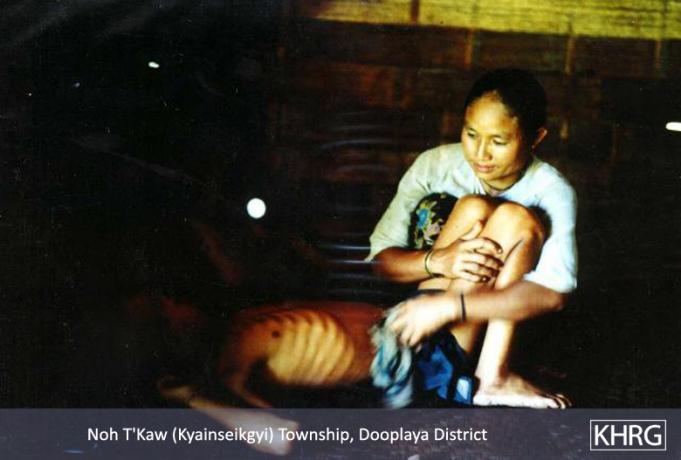

Deliberate attacks on villagers and their basic health infrastructure have receded since the signing of the 2012 preliminary ceasefire. A further change in villagers’ access to health is their perception of their safety and security to travel. Many villagers since the 2012 ceasefire report that feel safer to travel and face fewer restrictions on their freedom of movement, which has resulted in greater physical access to healthcare services.[13] Prior to this, life-threatening restrictions were imposed on villagers by Tatmadaw. Movement restrictions obstructed villagers living in supposed “rebel” or “black”[14] areas from travelling to reach hospitals or clinics, and from traveling outside of their home communities to buy medical supplies.[15] Villagers who did so risked being arbitrarily arrested, abused or shot on sight by Tatmadaw. Tatmadaw actively prohibited any medicine reaching these areas as part of their program to make sure no supplies could reach opposition forces, enforcing these restrictions at frequent checkpoints or arbitrarily searching villagers on roads and village paths to check they were carrying no medicine. These prohibitions were ultimately more deadly than Tatmadaw’s direct attacks:

“The villagers in hiding have also lost many people to disease. In every group of families there are people suffering from malaria and other fevers, diarrhoea, dysentery, oedema, respiratory and stomach ailments. Many more have died this way, particularly children and the elderly, than have been shot by the troops. None of the villagers have any medicines, they only have whatever herbal remedies they can find in the forest. Before this operation began they could walk to towns to buy medicine or medicine sellers would occasionally come through their areas, but no longer. Even in parts of eastern Shwegyin Township which should be an easy walk to Shwegyin Town, SLORC/SPDC[Tatmadaw] forces have blocked off all the paths since late 1997 in order to prevent these villagers from having any access to outside food or medicines.”

Report written by a KHRG researcher, Hpapun and Nyaunglebin Districts/ Kayin State (published in February 1998)[16]

Villagers caught with medical supplies had these items confiscated as part of the ‘Four Cuts’ policy and faced the risk of excessive abuse under the accusation that they were using medical supplies to support Karen ethnic armed groups (EAGs)[17] or trade with villagers in hiding, a common strategy used by villagers to support each other throughout oppression.[18] Villagers who were forcibly relocated faced further abuse as they were relocated to areas under strict Tatmadaw surveillance, without access to services including healthcare or medical supplies, forced to buy basic medicine at inflated prices from Tatmadaw medics, and were restricted from traveling outside of these relocation zones without paying extortive fees for permission letters in order to access hospitals or clinics when sick.[19]

Access to healthcare: consequences of human rights abuse

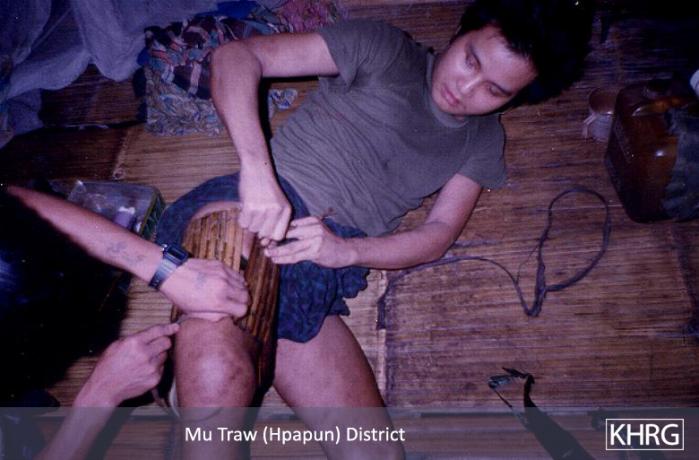

Villagers also report that they have faced life-threatening and debilitating health consequences as a direct consequence of abuse which has been worsened by the situation of healthcare service and standard. Villagers, most notably prior to the 2012 ceasefire, have been repeatedly subjected to violence, torture, killing, forced labour, and made to work as porters,[20] with severe and often long-term negative impacts on their health. Forced to work as porters, villagers have been tortured, made to carry heavy loads for long distances with enforced restrictions on food, water and medicine during their labour, resulting in severe weakness and, for some, death.[21] An escapee porter conscripted by Tatmadaw, Daw Ea--- from Thaton District, testified about the insufferable health consequences of portering:

“I had to carry bombs for 21 days through the forest and over mountains, into the areas where they’re fighting the Karen soldiers. It was almost impossible to keep up because the load was so heavy and we got almost no food. If we were lucky, [22] oncea day we got a little rice, but nothing to eat with it... We were all very weak, and many men and women were ill with chills and fever, but the hurt and sick were still forced to carry their loads and keep up, even if they had to bd dragged.”

Daw Ea--- (female, 32), quoted in a report written by a KHRG researcher, Kyaikto Township, Thaton District/northern Mon State (published in January 1992)[23]

Due to the inhumane conditions villagers have endured during portering and forced labour, villagers have suffered from various diseases and health ailments. Without adequate access to healthcare facilities and services, countless villagers have died of treatable diseases during decades of Tatmadaw’s oppressive control, often malaria or diarrhoea.[24] The abuses by Tatmadaw and at times EAGs therefore have had prolonged health impacts for villagers, including weakness, disease and death, that extend beyond the direct remit of violent abuse for which they can be directly held accountable for. The lack of acceptable and accessible healthcare services in southeast Myanmar therefore carries with it memories of negligence and abuse by Tatmadaw of villagers’ health under conflict.

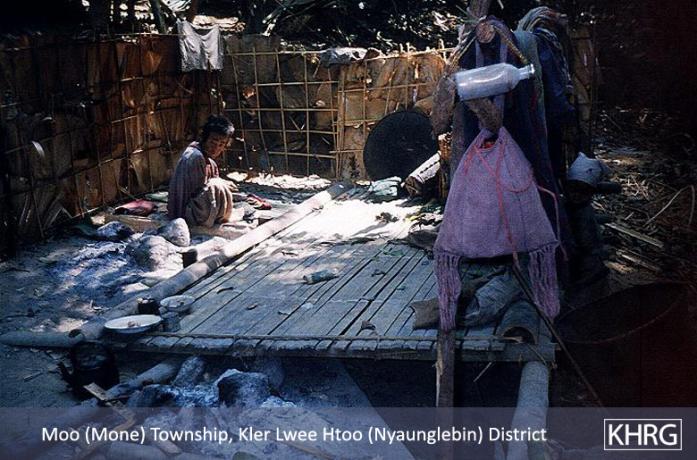

As a result of human rights abuses perpetrated by Tatmadaw and EAGs, many villagers chose to strategically displace themselves. This further limited their access to healthcare, and IDPs or villagers temporarily in hiding have faced some of the most severe health impacts of the conflict, dying from preventable diseases. Saw Eo--- describes the conditions of people hiding from Tatmadaw in Nyaunglebin District in 1999:

“The most common illnesses they suffer fromare fever and malaria. People with fevers or malaria who wouldn’t normally die are dying because there is no medicine. Most of the people who have died are children, ages 1 to years old. I saw children with fevers, and because they had no medicine the fever never went down. Even though they put sesame oil on t he body of the child, they still die. There is no gauze, no cotton and no medicine for when someone is injured. All they have are their traditional healing practices, but those are not perfect without some medicine as well.”

Saw Eo--- (male), quoted in Report written by a KHRG researcher, Nyaunglebin District/eastern Bago Region (published in May 1999)[25]

Access to healthcare: lack of investment in rural areas

Basic physical access to healthcare facilities therefore can be life-saving, including freedom of movement for villagers to travel to access clinics and medical supplies as well as the commitment to making more services at a higher standard available in rural areas. The lifting of restrictions and the reduction of the abuses of forced labour, torture and extrajudicial killings has evidently increased the potential for villagers to access healthcare, and the pressure has now turned to improving infrastructure and healthcare standards to support this. Whilst in some areas the situation of access to acceptable healthcare has improved, rural villagers continue to report significant barriers and remain at higher risk of sickness, disease and death than their urban neighbours. Much of the investment in improving healthcare access in recent years has largely focused on larger villages,[26] towns, and cities. Therefore, most villagers in rural areas continue to report that the distance they must travel to access the nearest hospital or clinic is too far, particularly in emergency cases.[27] Additionally, this distance burdens them financially due to travel costs, and is especially difficult for vulnerable populations such as pregnant women and elderly villagers.[28] Saw Es---- in Htee Th’Blu Hta village tract, Hpapun District, 2016, describes the as yet un-met need for improved infrastructure and healthcare services in rural areas:

“When I was sick, my neighbours had to carry me to the hospital on a bad [unpaved] road. Therefore, if people [authorities] construct a better road for us then it will be a good thing for us. If we have a good road then we can go to hospital by car, then we will arrive to hospital quickly. There is no hospital in the eastern area [where the rural villages are located] so we have to go to the western area [where the town is located].”

Saw Es--- (male, 45) Et--- village, Htee Th’Blu Hta village tract, Bu Tho Township, Hpapun District / northeastern Kayin State (interviewed in December 2016)[29]

The Myanmar government has taken steps to address this void in services for the rural population, attempting to train and dispatch health workers to rural areas in southeast Myanmar where they previously were not working. However, physical access such as inadequate roads and bridges reinforces the isolation of these villages, as many health workers cannot access them, or are unwilling to access them:

“Although theTownshipadministratorsendsa doctor from Thandaunggyi Township [to the villages], the doctor does not go to the villages since there is problem for the car to travel there. The road which goes to the villages that the doctor has to take for treating the [villagers’] illnesses takes three hours by motorcycle. The road is also rough since it was constructed by the villagers. The doctor said, “I cannot sacrifice myself,” and he turned back at the half way [point].”

Situation Update written by a KHRG researcher, Thandaunggyi Township, Toungoo District/northern Kayin State (received in November 2015)[30]

Myanmar government health workers being absent from their appointed villages, as evident in the above case, have serious consequences for villagers in need of healthcare, such as the death of a mother in child birth:

“On May 29th 2014, in Toungoo District,Thandaunggyi Township,a villager from A--- village delivered her baby. There were mid-wives appointed by the [Burma/Myanmar] government, but they were never in the village. She had to deliver the baby with a hired [non-formally trained] midwife. Because she delivered the baby with a hired mid-wife, it took so long that her placenta did not come out and the hired mid-wife [had to] cut her placenta out with scissors. The blood ran without stopping and she died. If there were mid-wives [from the Burma/Myanmar government] and medicine, we could have saved the pregnant woman”.

Situation Update written by a KHRG researcher, Thandaunggyi Township, Toungoo District/northern Kayin State (received in July 2014)[31]

The above case shows that even when Myanmar government health workers have been appointed in rural areas, they often do not stay in the village reliably or permanently, leaving villagers to rely on unskilled, traditional medics. In many cases where government health workers refuse to go to rural areas despite the health needs of villagers, they are also unwilling to stay in the villages because of poor living conditions, further deteriorating rural villagers’ access to healthcare.[32] As noted by a community member in Bilin Township, Thaton District in 2014:

“In Ec---village, the Myanmar government setup a clinic for the villagers but the government health worker who is going to take care of the villagers does not want to live amongst the Karen people. I heard from the villagers that she said that if she is given the responsibility of injecting vaccines [for the villagers], she will come and inject the vaccine and then she will return to her village.”

Situation Update written by a KHRG researcher, Bilin Township, Thaton District/northern Mon State (received in November 2014)[33]

The above testimony by a KHRG researcher suggests that not only physical barriers of a lack of clinics and infrastructure in rural areas impact villagers’ access to healthcare, but also ethnic divisions continue to impact the adequacy of healthcare that Karen villagers receive, as a trained, appointed Myanmar government health worker does not want to live “amongst the Karen people”.

In some areas however, villagers report that there has been a marked increase in the number of Myanmar government health services available,[34] including both the number of staff and number of newly constructed clinics. Naw Ew--- from Kyaukkyi Township, Nyaunglebin District in 2016 notes Myanmar government staff are now more present in her area and villagers feel safer to contact them:

“Regarding healthcare, in the past it was not easy to call a Myanmar government doctor if we were sick. Now there are Myanmar government doctors entering our village. Our Karen people are just health workers [without full medical training]. Therefore, if we get a serious illness, we just call the Myanmar government doctor. In the past, when we were sick, we dared not to call doctors at night. That is why some sick people suffered until they died. After the ceasefire, we dare to go to call the doctors to come and provide medical treatment whenever we want to.”

Naw Ew--- (female, 24), Ex---- village, Khel Ken Koh village tract, Kyaukkyi Township, Nyaunglebin District/eastern Bago Region (interview received in December 2016)[35]

However, villagers report that many healthcare facilities that have been established in the post- ceasefire period are poorly constructed and lack trained medical staff, equipment, and essential medicines.[36] As reported by Saw PP--- from Dooplaya District in 2016:

“Currently, there is hospital but there are no medics and medicine. And sometimes there is medicine but there are not enough different types of medicines so [villagers] have buy [medicine from outside].”

Saw PP--- (male, 37), Win Yay Township, Dooplaya District/southern Kayin State (interview received in November 2016)[37]

In addition to a lack of supplies and staff, due to a lack of consistent funding and oversight by the Myanmar government or the authority responsible for the construction, some newly constructed healthcare facilities never open[38] or are defunct as soon as the opening ceremony has been completed.[39] One KHRG researcher from Thaton District reported to KHRG in 2014:

“We [the community] need more healthcares [professionals] in this area [ThatonTownship].The Myanmar government built clinics in many places but there are no nurses or medics.There are no people who look after these buildings so some of the buildings were destroyed and some became goat pens.”

Situation Update written by a KHRG researcher, Thaton Township, Thaton District/northern Mon State (received in July 2014)[40]

Access to healthcare: communication and coordination

Given both the lack of access and void in rural areas of functioning and culturally appropriate Myanmar government healthcare facilities, villagers have consistently relied on a number of different actors to fill the gaps in service provision. Most of these services are provided by Karen healthcare CBOs and the Karen Department of Health and Welfare (KDHW) under the KNU administration, neither of which could operate openly under conflict for risk of being accused of supporting Karen EAGs through their work.[41] However, one villager in Hpa-an District reported in 2014 that the Myanmar government has not given the option for healthcare services to be KNU- led or self-reliant and community-led, asserting its presence in areas where villagers state their preference for services provided by local actors instead of the Myanmar government:

“[W]e heard that they [the Burma/Myanmar government] came and built hospitals in Klaw Ga Di village and Shan Ywa Thit village. But they do not allow Karen [KNU] to build a 50 bed or 100 bed hospital in Paingkyon Town.”

Saw A--- (male, 36), C--- village, Nabu Township, Hpa-an District/ central Kayin State (interviewed in May 2014)[42]

Since the 2012 ceasefire, there has also been an increase in health CBOs operating in rural southeast Myanmar. While these CBOs often provide essential vaccinations and basic medical supplies to villagers in rural areas, villagers have raised concerns over the unpredictability of their services due to a lack of consultation and communication between villagers and the healthcare provider. This lack of communication and consultation is evident in many services that are provided in southeast Myanmar,[43] and has resulted in confusion among villagers and an overlap in services in some areas whilst a void continues in other areas. For example, a KHRG researcher from Dooplaya District reported in 2014:

“There are two township clinics that were opened by the KNU which are free of charge. Although each township has [Burma/ Myanmar government] Anti-Malaria Teams, there are [additional] government organisations and association sentering the community [other than the] Anti-Malaria Team, including Mother and Child Care and Polia Protection and Immunisation and Anti-Tuberculosis. Villagers do not know which injection they should get and they also worry that they will not get the right injection. In 2013 a medical complication arose after a villager had an injection for elephantiasis. [44] Because of the 2013 medical complication, villagers were concerned with which health teams [or organisations] will arrive news to give help.”

Situation Update written by a KHRG researcher, Win Yay Township, Dooplaya District/southern Kayin State (received in November 2014)[45]

As the above report suggests, healthcare providers have been active in increasing health awareness trainings to villagers after the preliminary ceasefire, although many areas remain poorly serviced and lack permanent healthcare staff.[46] Additionally, villagers have found that they are not consulted on their health priorities with regards to the trainings that are available, and do not know the schedule of when these mobile teams will return to their community.[47]

However, the presence of KNU medics and CBOs has provided essential, if not consistent or extensive, healthcare for villagers particularly in more remote areas and for villagers who face financial barriers to traveling and accessing Myanmar government hospitals, easing some villagers’ health concerns. According to one KHRG community member from Thaton District in 2015:

“Those who live near towns go to town for treatment. Those who have insufficient money for treatment, theyfindtheir own ways of treating their illnesses. In KNU side [KNU-controlled areas], BackPack[48] has setup clinics in every area. Therefore, those who cannot afford to go to town [for treatment] try to go to the KNU side [clinics], where they also receive enough medicine”

Situation Update written by a KHRG researcher, Thaton Township, Thaton District/northern Mon State (received in November 2015)[49]

The reliance on CBOs and local Karen medics due to inadequate Myanmar government services is evident throughout KHRG’s 25 years and the presence of these local organisations has been life-saving for villagers in hiding or immobile due to severe movement restrictions and poor infrastructure.[50] However, even with these various actors providing services in rural areas, many villagers have suffered over 25 years from inadequate access to healthcare facilities and services. The recent improvement in quantity of healthcare buildings has done little to improve the health of villagers on the ground if the services remain unstaffed, without medicine, and without coordination or consultation by different service providers.

Acceptability of healthcare: inadequate staff and skill

In addition to concerns with regard to lack of access, villagers have consistently raised their concerns over quality of healthcare services. In recent reports, notably since 2014, when clinics and healthcare services are staffed, villagers also report that the quality of the services provided by Myanmar government health workers is poor. The lack of trained medical staff, generally supplied by the Myanmar government, will take longer to overcome than the lack of a physical building or well-stocked medicine cabinet. The training that both KNU medics and Myanmar health workers receive is too brief to secure the knowledge and skills necessary to provide quality healthcare services to villagers. As a result, when healthcare services are available, insufficiently trained health workers can often do little to address villagers’ health concerns and simply refer sick villagers to other clinics which are further away:[51]

“The health workers were elected to work for the health service but they are not well trained or qualified to treat serious patients so, the villagers have to face challenges. For the villagers who face serious diseases, most of them go to town for the medical treatment.”

Saw Eh--- (male, 24), Ei--- village tract, Thaton Township, Thaton District/ northern Mon State (interview received in November 2016)[52]

In addition to not being well trained or qualified, villagers report that these health workers often fail to communicate effectively with their patients and results in many villagers currently not knowing their health options and being uncertain whether it is safe to take certain medicines, such as in the area of reproductive health, with serious health consequences:

“[There is a] lack of health awareness at the Township level. […] In ruralareas, women do not want to use contraceptive pills because they are afraid to use them. There is no effective awareness [conducted]. If there is effective awareness, there would be no big concern [for them to use contraceptive pills]. In Kyaukkyi Town, many women had not given birth to their child successfully [they have faced birth complications]because they lack access to [health] awareness. They do [not] have knowledge on what to do and what not to do [when getting pregnant and giving birth]. Moreover, there are few health workers. In Karen State [southeast Myanmar], [pregnant] women in the villages are not well taken care by the [health workers]. Because women have a lack of knowledge about reproductive health, about what to do and what they should not do, about one third of women who got married after [they turned] 18 years old have lost their baby [in childbirth or infancy].”

Naw Ej---- (female, 38), Ek---- section, Kyaukkyi Township, Nyaunglebin District/ eastern Bago Region (received in February 2016)[53]

Problems of poor communication between health workers and patients, a lack of awareness for patients about their health options, and poorly trained medical staff, are evident also in recent cases where healthcare providers have denied patients treatment for no evident reason,[54] failed to communicate how to safely and effectively use prescribed medicine and medical supplies,[55] acted negligently by failing to discuss potential side effects of treatment with patients,[56] and been unable to offer effective treatment to patients in need.[57] This is aggravated by the lack of culturally appropriate staffing in southeast Myanmar, with many Myanmar government-appointed healthcare staff being unable to speak Karen and therefore unable to communicate with patients effectively.[58] For this reason, villagers have reported serious side effects after receiving vaccinations from insufficiently trained health workers, and lack trust in some Myanmar government health workers to work in the best interests of the patient.[59] These experiences do little to empower villagers to respond to their own health needs. Furthermore, reports of poor communication do little to encourage villagers to access Myanmar government services where they are made available.

Access to healthcare: livelihood and financial insecurity

An additional concern with regard to access to healthcare for villagers in southeast Myanmar is their livelihood and financial insecurity. For villagers able to access Myanmar government health facilities such as those located in larger towns, particularly in the post-ceasefire era, the cost of healthcare services and prescribed medicines have been described as unaffordable.[60] This financial barrier has been present throughout KHRG’s 25 years reporting period. Villagers throughout the reporting period have faced debt in order to pay for the cost of medicine and medical treatments for their family members[61] while some have sold personal possessions to cover these expenses.[62] According to Saw PP--- from Dooplaya District in 2016:

“For some widows, they do not have money therefore they sell their land or borrow money from others and they are in a situation of debt. They receive medical treatment and have to repay their debts as well, so they cannot be safe from debt.”

Saw PP--- (male, 37), Win Yay Township, Dooplaya District/ southern Kayin State (interview received in November 2016)[63]

Poorer villagers who struggle to pay for the cost of healthcare services identify a further barrier in accessing adequate services, reporting that they are discriminated against with regard to priority health treatment or are not treated at all. This is the case with both private and public health workers who have discriminated against poorer patients.[64] In this case, poorer patients report that they are ignored by health workers,[65] feel pressured to pay more money to receive better treatment,[66] and receive sub-standard care due to their financial status.[67] The benefits of good quality healthcare therefore remain inaccessible to villagers who do not have sufficient finances. This has significant impacts, as noted by one KHRG researcher in Thandaunggyi Township, 2014:

“There is one thing; naturally, some medics only look for their self-profit and they do not fully sacrifice or show their benevolence to the patients [by treating poorer patients]. For the rich people, as they have money, they do not have to face big problems [to access medical treatment]. Because of having a shortage of medicine, [villagers] have to face problems in many ways and some people have lost their lives for nothing [because they could not afford treatment or access medicine].”

Situation Update written by a KHRG researcher, Thandaunggyi Township, Toungoo District/northern Kayin State (received in July 2014)[68]

These financial concerns over both access and acceptability of treatment are raised in a context where many villagers report recurring livelihood insecurities and financial instability. Villagers’ livelihood insecurities have been present throughout 25 years of KHRG reports and have continually impacted their basic health and survival, as villagers have been forced to pay for basic medicines which should have been supplied by Myanmar government for free:

“The SPDC [Tatmadaw / Myanmar government], when it does allot money to build a clinic, will not provide medics with training, nor give the village money for medicine. In many cases medics must buy medicine for the village with their own money, then rely on the villagers to pay them back. When supplies are short villagers must cope with saline injections and Paracetamol as the only available treatment unless it is serious enough to make a journey to the nearest hospital, often many days’ journey by foot.”

Report written by a KHRG researcher, Dooplaya District/ southern Kayin State (published in March 2000)[69]

Additionally, through abuse by armed actors, namely Tatmadaw, villagers according to KHRG reports have been forced into states of poverty and financial insecurity, directly impacting their health. Due to constant demands for forced labour evident in KHRG reports between 1992 and 2012, with some districts reporting cases of forced labour ongoing in 2015 and 2016, villagers have often been left with little time to devote to their farms and other income generating activities, negatively impacting their livelihood, finances and food security.[70] These concerns have been compounded by Tatmadaw’s direct theft and destruction of land, food stores, and means of food production during village attacks in the 1990s most commonly, but also in the late 2000s.[71] The abuses of theft, looting, extortion, land confiscation and forced labour have weakened traditional livelihood subsistence, directly impacted villagers’ food security, financial security and, therefore, their physical health. As such, villagers throughout KHRG’s reporting period have been left with little money to spend on health services or medications, forced to go without treatment or to sell their remaining possessions for treatment.[72]

Serious livelihood struggles have been heightened in cases of severe health problems caused by abuse, and the right to health is repeatedly identified by many villagers as essential in order to secure their own livelihood.[73] For example, villagers who have been left disabled after being shot or maimed by landmines have reported the difficulty of securing their livelihood after the abuse.[74] This concern is intensified by the lack of adequate support services that can support survivors of serious abuse, and in some cases during KHRG’s reporting period has led villagers to take their own lives, such as 18 years old Saw Ed--- from Ee--- village, Toungoo District, in 2007:

“In the rainy season Saw Ed- was forced to porter food supplies for the soldiers of [Tatmadaw] MOC#5. During this forced labour, he was made to act as a human minesweeper at the front of the patrol and consequently lost a leg when he stepped on a landmine. On returning from hospital, he discovered his wife had no remaining rice left to cook for them. Knowing the difficulties he would face without his leg and the situation he and his wife were already facing, he also decided he didn’t want to continue his life and hung himself on September 10th 2007.”

Commentary written by a KHRG researcher, Toungoo District/ northern Kayin State (published in December 2007)[75]

Of concern, villagers living with disabilities related to landmine incidents or other physical effects of the conflict continue to suffer due to the void in adequate health services and no additional welfare support. It is therefore pertinent that villagers, particularly those who have lived through sickness, abuse and poverty, continue to face the health consequences of insecure livelihoods and finances with regards to access and acceptability of health services, highlighting that healthcare has not been and continues to not be free, with equal treatment and equal access for villagers in southeast Myanmar.

Access to healthcare: reliance on traditional medicine

The lack of trained healthcare staff, deficient health infrastructure, and poor experiences with some health workers means that villagers continue to rely on local medics with uncertain levels of training for their healthcare, which in some cases has significantly worsened villagers’ health problems. Additionally, as a result of the lack of available, accessible, and affordable healthcare services, many villagers in rural areas rely on the use of traditional medicine or buy non-prescribed medications to treat their medical ailments, a common agency tactic also during conflict.[76] Under these circumstances, little appears to have changed over 25 years. In 2014, a community member from Toungoo District reported:

“For some villagers, when they are sick they just work it out in their own way by buying oral medicine or intravenous medicine from the shops, [while] some just heal the sickness by traditional medicines from the plants. If a critical illness happens [to a villager] and if they go to the hospital it is expensive and there are patients who cannot afford to go to the hospital. Because of these reasons, some villages’ patients pass away without having a chance to go to the hospital, as they cannot afford to go to the hospital.”

Situation Update written by a KHRG researcher, Thandaunggyi Township, Toungoo District/ northern Kayin State (received in November 2014)[77]

During conflict villagers who could not access healthcare facilities or medics due to physical, economic, or safety barriers also relied heavily on the use of local healers and traditional medicine even to treat serious illnesses and wounds.[78] This reliance was most acute for villagers in hiding or those who had fled abuse, who had no option to access health services or basic medicines, such as IDPs from Nyaunglebin District in 1999:

“They have no medicines and speak of treating gunshot wounds by applying sesame oil after saying incantations. When the interview was done villager sent out a plea for help with supplies of rice, cookpots and medicines, saying that other things they can make from the forest but not these.”

Field report written by a KHRG researcher, Nyaunglebin District/ eastern Bago Region (published in February 1999)[79]

Conclusion

The cases analysed and presented here demonstrate the persistent void in healthcare services in southeast Myanmar over 25 years, and the life threatening consequences that this continues to have. Whilst some recent developments have been hailed as improvements, such as the increased construction of clinics and hospitals, and the lifting of restrictions on freedom of movement and trade of medical supplies, this chapter demonstrates that many essential healthcare services remain both inaccessible and unacceptable, particularly for vulnerable and rural populations in southeast Myanmar. Severe barriers to security of health under conflict due to movement restrictions, prohibitions on medicine, displacement and forced relocation have diminished, only to be overshadowed by physical barriers of poor roads preventing both patients travelling to hospitals and health workers travelling to villages, and the lack of permanent health workers in rural areas result in continued cases of villagers not receiving the treatment that they need, often urgently. The result is the same: that villagers in southeast Myanmar do not have adequate access to healthcare services, and sickness and death from otherwise preventable cases continues to be the result.

Moreover, villagers’ voices presented here testify that when services are available, the quality remains unacceptable, with cases of discrimination by health workers against poorer patients, patients receiving incorrect treatment, and patients lacking access to the necessary medicines. Additionally, a significant barrier to accessing adequate healthcare for villagers in southeast Myanmar which is yet to be removed is financial, as throughout KHRG’s 25 years analysis villagers’ have reported the severe financial consequences of both abuse and health treatment, with many falling into debt in order to pay for even basic healthcare. Villagers have used their own strategies to maintain health, relying on the use of traditional herbal medicine and local healers, but these cases fall short of acceptable health standards and villagers express their desire for improved access to health in all areas.

Ultimately, whilst the most severe restrictions and abuses which impacted villagers health during conflict have reduced, it is concerning to see that the necessary services have not been established in the post-ceasefire period to the extent and standard that is urgently needed. The result is that, whilst the extreme and immediate health consequences of abuse and conflict are no longer present in KHRG reports, villagers remain blocked from enjoying their right to full health.

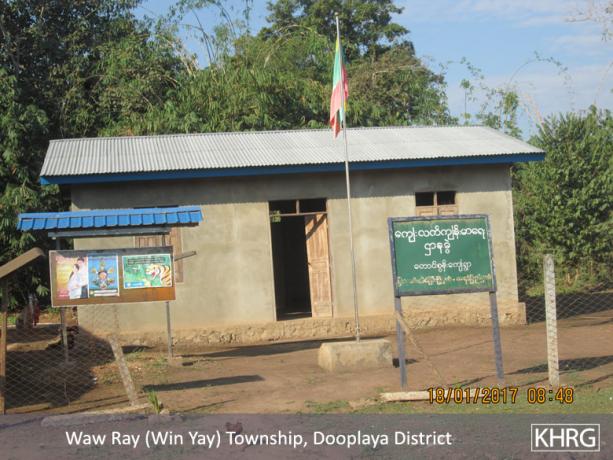

This photo was taken on January 18th 2017 in Taung Soe village, Si Pyay village tract, Win Yay Township, Dooplaya District. This photo shows a local clinic in Taung Soe village. According to villagers, there are not enough health workers at this clinic and the health workers do not always stay at the clinic so villagers continue to face troubles when they are sick. [Photo: KHRG][80]

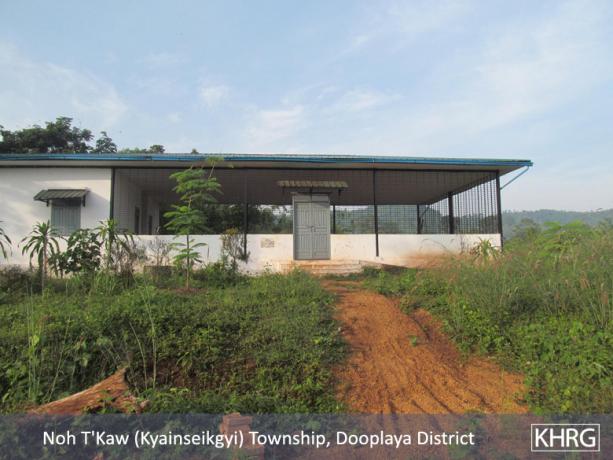

This photo was taken on November 29th 2015 in Tha Main Dwut village, Tha Main Dwut Village Tract, Kawkareik Township, Dooplaya District. It shows a clinic constructed by the Myanmar government health department. However, since the clinic was constructed there have been no health workers or medicines. For these reasons, villagers couldn’t use it. [Photo: KHRG][81]

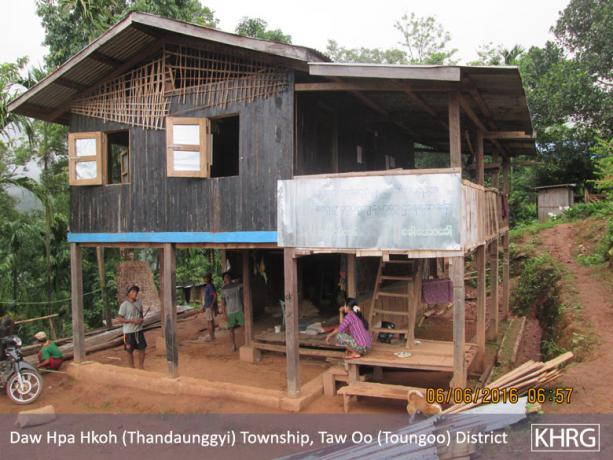

This photo was taken on June 6th 2016, in Cow Thaw Cow village, Hon Thaw Plo village tract, Thandaunggyi Township, Toungoo District. It shows a KDHW clinic with health administrators who operate under the KNU health department. The health workers do not have enough medicines however they try to take care of local villagers as much as they can. [Photo: KHRG][82]

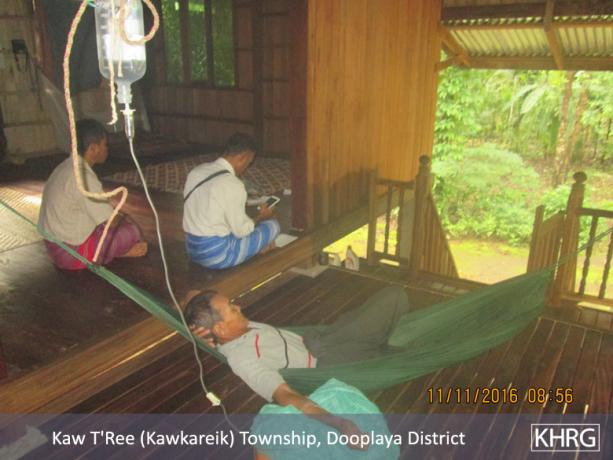

This photo was taken on November 11th 2016 in Tha Main Dwut village, Tha Main Dwut village tract, Kawkareik Township, Dooplaya District. It shows members of the Backpack Health Worker Team (BPHWT) trying to help sick villagers by giving them medical treatment for free in Tha Main Dut village. [Photo: KHRG][83]

This photo was taken in September 2014. It shows a clinic that was built by the Myanmar government in order to improve the health of the villagers in Kah Lee Kee village, Kyainseikgyi Township, Dooplaya District. In the past year villagers report that they have suffered from various diseases and that some villagers have died for treatable diseases. However, they report that the health situation is getting better compared to the past because now the clinic is available in the village. [Photo: KHRG][84]

This photo was taken on April 20th 2014 in Kyoh Kah Loh village, Htee Th’Daw Htah village tract, Buh Tho Township, Hpapun District. This photo shows a clinic constructed by an unknown NGO, with some involvement from the Myanmar government. The clinic was completed in 2012. This clinic aims to help villagers to get access to healthcare close to their area but until now villagers have not seen any medicine, only clinic construction. Villagers at the time this photo was taken did not have any information about whether they will get medicine in this clinic or not. [Photo: KHRG][85]

This photo was taken on December 27th 2014 at Leik Tho Town, Thandaunggyi Township, Toungoo District. It shows a free healthcare service provided at the public hospital. The service is led by the local KNU government and medical specialists. [Photo: KHRG][86]

This photo was taken on April 19th 2014 in Meh Lah Htah area, Htee Th’Daw Htah village tract, Bu Tho Township, Hpapun District. It shows a women suffering from an unknown illness. She cannot access proper treatment or prescription medicine due to the cost of travel and treatment, and the distance to the hospital. Instead her husband is making a traditional herbal and leaf medicine for her. [Photo: KHRG][87]

IDP villagers in Lu Thaw Township, Hpapun District are shown here on March 4th 2009, having come to D--- IDP camp in order to receive medical treatment from a mobile Karen medical team. Such aid, delivered by local Karen staff working with small mobile medical teams which obtain supplies from across the border in Thailand remains crucial means by which IDP communities are able to address their health needs. [Photo: KHRG][88]

This picture, taken on September 10th 2009, shows 39 years old convict porter Maung Tha---, who escaped after being taken from prison and forced to carry supplies for LIB #212. Maung Tha--- had been serving a 7 years term. He was sent to act as a porter on December 5th 2008. He told KHRG he escaped because he could no longer bear the heavy loads and verbal and physical abuse by soldiers. On his right shoulder can be seen scars from sores developed while carrying his loads. [Photo: KHRG][89]

This photo from a 2000 KHRG report shows the body of villager Saw Maw Toh from K--- village in western Lu Thaw township, Hpapun District. Saw Maw Toh, aged 40, had fled with other villagers when Light Infantry Division #66 destroyed their village, but then died of illness in the forest because there was no medicine. He leaves a wife and 2 children aged 1 and 9. [Photo: KHRG][90]

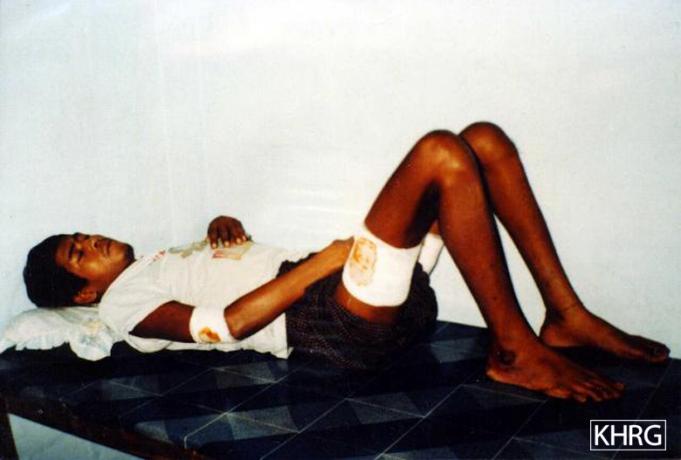

This photo from a 2000 KHRG report shows a sick villager staying in his hiding place Mone Township, Nyaunglebin District, unable to leave to access medicine. Tatmadaw troops had been sweeping their area since November, causing many villagers to go into hiding. This villager has been sick but has not got medicine. Thousands of internally displaced villagers were living in hiding in the forested hills with little food and no medicines during this time, dodging Tatmadaw patrols which systematically destroyed their shelters and food supplies. [Photo: KHRG][91]

This photo is of a villager in Hpapun District, 1994, who was shot from behind by a Tatmadaw patrol as he was fleeing to avoid being taken as a porter. The bullet entry wound is in the back of his right thigh, and the larger exit wound on the front of his thigh. He is having the wound cleaned with a needle and a string soaked in antiseptic, without anaesthetic. His bandage is a rag held on with a bamboo legging. [Photo: KHRG][92]

This photo shows a mother and her son in Kwih Kaneh Khoh village, Kyainseikgyi Township, Dooplaya District, November 1996. On 27th October 1996 a column of Tatmadaw troops attacked and looted Kwih Kaneh Khoh village, Kyainseikgyi Township, Dooplaya District (southwest of Kyaikdon). The village was completely undefended and the troops marched into all 30 houses and looted everything, leaving the villagers with nothing. Just afterwards this woman’s son fell sick, and when this photo was taken 3 weeks later he could no longer move. Tatmadaw does not allow medical supplies to enter this area. [Photo: KHRG][93]

This photo from a report by KHRG in 1997 shows Maung PQ---, aged 28, a Muslim villager from Myawaddy Township, Dooplaya/Hpa-an District, who was taken as a frontline porter in 1996 even though he was already sick with malaria. Two weeks later he collapsed under his 40-kilo load of mortar shells, so he was kicked and beaten unconscious by the commander and kicked down a slope to die. Other porters escaped later and returned to find him and carry him to Thailand. Doctors operated 3 times, drained 1.5 litres of pus from his arm and thigh, and found he had a permanent corneal scar, a broken rib, serious damage to his arm, and the muscles of his thigh were so badly beaten that he will never walk properly again, all from the beatings. He was not even strong enough to be interviewed until one month later. [Photo:KHRG][94]

This photo, taken in eastern Nyaunglebin/Hpapun District, shows a woman who had fled her hill village due to Tatmadaw attacks in 1997. The woman is hiding in a forest shelter and had been down with serious dysentery for several days. She had no medicine, and could die from this illness.[Photo: KHRG][95]

This photo from a 1994 KHRG report shows a sick and malnourished baby Karen girl in Thaton district. Infant mortality in these areas was extremely high due to Tatmadaw offensives, looting, extortion, and the Tatmadaw blockade against any medicines entering this ‘insurgent’ area. [Photo: KHRG][96]

Footnotes:

[1] “DEATH SQUADS AND DISPLACEMENT,” KHRG, May 1999.

[2] “Thaton Situation Update: Thaton Township, January to June 2015,” KHRG, January 2016.

[3] Article 25, “Every one has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services.” “Universal Declaration of Human Rights,” United Nations General Assembly, December 1949. Myanmar was one of the first countries to vote in favour of adopting this non-binding Declaration.

[4] Article 12, “The States Parties to the present Covenant recognize the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the high estattainable standard of physical and mental health.”“International Covenant on Economic,Social and Cultural Rights,” United Nations General Assembly, 1966. Myanmar signed the ICESCR in July 2015.

[5] “CONSTITUTION ON THE REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR,” September 2008.

[6] The killing or denial of medical treatment to the wounded in conflict is a grave breach of the Geneva Convention of 1949, see Article 3.2: “The wounded and sick shall be collected and cared for.” Geneva Convention, 1949.

[7] Article 18, “Civilian hospitals organized to give care to the wounded and sick, the infirm and maternity cases, may in no circumstances be the object of attack but shall at all times be respected and protected by the Parties to the conflict.”“Convention (IV) relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War,” International Committee of the Red Cross, August 1949. See also “Customary IHL: Rule 28. Medical Units,” International Committee of the Red Cross, 2012.

[8] Source #165.

[9] Tatmadaw refers to the Myanmar military throughout KHRG’s 25 years reporting period. The Myanmar military were commonly referred to by villagers in KHRG research areas as SLORC (State Law and Order Restoration Council) between 1988 to 1997 and SPDC (State Peace and Development Council) from 1998 to 2011, which were the Tatmadaw-proclaimed names of the military government of Myanmar. Villagers also refer to Tatmadaw in some cases as simply “Burmese” or “Burmese soldiers”.

[10] In Burma/Myanmar, the scorched earth policy of ‘pyatlaypyat’, literally ‘cut the four cuts’, was a counter- insurgency strategy employed by the Tatmadaw as early as the 1950’s, and officially adopted in the mid-1960’s, aiming to destroy links between insurgents and sources of funding, supplies, intelligence, and recruits from local villages. See Martin Smith. Burma: Insurgency and the Politics of Ethnicity, New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1999 pp. 258-262. See also, “GRAVE VIOLATIONS: ASSESSING ABUSES OF CHILD RIGHTS IN KAREN AREAS DURING 2009,” KHRG, January 2010; and “Attacks and displacement in Nyaunglebin District,” KHRG, April 2010.

[11] “Papun and Nyaunglebin Districts, Karen State: Internally displaced villagers cornered by 40 SPDC Battalions; Food shortages, disease, killings and life on the run,” KHRG, April 2001; see also “Photo Set 2002, Section 2: Attacks on Villages and Village Destruction,” KHRG, December 2002. Attacking medical units is recognised as a grave breach of customary international humanitarian law. See, “Rule 28. Medical Units,” International Committee of the Red Cross, 2012. It is a breach of the Fourth Geneva Convention, Article 18, “Civilian hospitals organized to give care to the wounded and sick, the infirm and maternity cases, may in no circumstances be the object of attack but shall at all times be respected and protected by the Parties to the conflict.” “Convention (IV) relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War,” International Committee of the Red Cross, August 1949.

[12] “Tenasserim Interview: Saw K---, August 2011,” KHRG, September 2011.

[13] Source #115; see also “[The two biggest challenges facing the community are] [h]ealth and conflict between Tatmadaw and other ethnic armed groups. These two things are important.”Source #168.

[14] Tatmadaw expert Maung Aung Myoe explains that the three-phased Tatmadaw counter-insurgency plan, developed in the 1960s, designates a territory as black, brown or white according to the extent of ethic armed group (EAG) activity. Phase one transforms a ‘black area’ into a ‘brown area,’ meaning it transforms from an area controlled by EAGs where the Tatmadaw operates, to a Tatmadaw-controlled area where EAGs operate. The second phase is to transform the area from a ‘brown area’ into a ‘white area,’ where the area is cleared of insurgent activities. The final phase is to transform a white area into a ‘hard-core area,’ during which more organisational works are necessary and the government forms pro-government military units for overall national defence. See Maung Aung Myo, Building the Tatmadaw: Myanmar Armed Forces Since 1948, Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2009, p. 31-32; see also Neither Friend Nor Foe: Myanmar’s Relations with Thailand Since 1988, Singapore: Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies Nanyang Technological University, 2002, p. 71.

[15] These restrictions were reported by KHRG as recently as 2009 in Toungoo District: “OnNovember20th,2009,MOC#5beganblocking villagersfromKlerLaandGkawThayDer, TantabinTownshipfromtravellingontheroad to Toungoo.This occurred ata time when such a large number of individuals from areas around Kler La and Gkaw Thay Der were suffering from the flu and other winter illnesses that the Kler La hospital was full to the point of turning away patients. The movement restrictions prevented individuals from villages without medical facilities or medicines from travelling to Kler La to seek treatment, while preventing individuals already in Kler La but not admitted to the hospital from travelling to other towns or cities to get treatment or medicines. The situation was reported to SPDC [Tatmadaw] officials but the restrictions were not adjusted or relaxed. Such restrictions, which are particularly harmful for vulnerable populations such as children in need of medical treatment, are considered a ‘grave violation’ of children’s rights and explicitly condemned by United Nations Security Council Resolution (UNSCR) 1612.” “Forced Labour, Movement and Trade Restrictions in Toungoo District,” KHRG, March 2010.

[16] “The SLORC/SPDC Campaign to Obliterate All Hill Villages in Papun and Eastern Nyaunglebin Districts,” KHRG, February 1998; see also “Toungoo Situation Update: April 2011,” KHRG, June 2011; “ATTACKS ON KAREN REFUGEE CAMPS,” KHRG, March 1997.

[17] “The prohibition on carryingmedicinemeans that it must be bought and carriedsecretlytothe villages.The carrier risksbeingaccusedofsupplyingmedicinetotheresistanceandprobableexecution.”“PEACE VILLAGES AND HIDING VILLAGES: Roads, Relocations, and the Campaign for Control in Toungoo District” KHRG, October 2000; see also “Papun and Nyaunglebin Districts, Karen State: Internally displaced villagers cornered by 40 SPDC Battalions; Food shortages, disease, killings and life on the run,” KHRG, April 2000.

[18] “Forced Labour, Movement and Trade Restrictions in Toungoo District,” KHRG, March 2010.

[19] “They didn’t provide food [at the relocation site]; the people had to bring their own food to eat. If you want to take medicine, you haveto buyitand ifyou don’t buy it, you can’thavemedicine.Sometimes youcantrade itfor chicken:2 tablets of para [Paracetamol] for ½ viss of chicken. But they don’t give it to you for free. You have to trade with the Burmese soldier’s medic.” “STARVING THEM OUT: Forced Relocations, Killings and the Systematic Starvation of Villagers in Dooplaya District,” KHRG, March 2000.

[20] “Tenasserim Division: Forced Relocation and Forced Labour,” KHRG, February 1997; see also “INCOMING FIELD REPORTS,” KHRG, August 1994.

[21] See, for example, the testimony of Saw Eu---, 27 years old who was forced to porter in 1992 and saw 4 fellow porters be left behind to die due to weakness: “Isawit4 times. The men got malaria and couldn’t carry, so the soldiers kicked them and let them sit down, then they beat them up and left them behind. I got malaria and asked for water when we were climbing mountains. They refused to give me water and I cried. I couldn’t help crying all the time. I wanted to unload my burden but they wouldn’t allow me. I needed water, but they wouldn’t let me have any.” “PORTER TESTIMONIES: KAWMOORA REGION,” KHRG, December 1992. The killing of wounded prisoners or combatants in conflict is a grave breach of the Geneva Convention, see 3.2: “The wounded and sick shall be collected and cared for.” “Geneva Convention relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War: 75 U.N.T.S. 135,” International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), October 1950.

[22] This word has been correctly amended to ‘lucky’ from ‘luckily’ in the original published report.

[23] “TESTIMONY OF PORTERS ESCAPED FROM SLORC FORCES,” KHRG, January 1992.

[24] “The health situation for the internally displaced villagers is very serious. There is no medicine in the Ywa Bone villages and they are completely dependent on traditional medicines made from roots and leaves. Without letters of recommendation it is impossible to send people to Kler Lahor Toungoo for treatment. Twenty displaced people from Ha Toh Per village died from diarrhoea in 1999, simply due to a lack of basic medicines.” “PEACE VILLAGES AND HIDING VILLAGES: Roads, Relocations, and the Campaign for Control in Toungoo District,”KHRG, October 2000; see also “ABUSES AND RELOCATIONS IN PA’AN DISTRICT,” KHRG, August 1997; “Papun and Nyaunglebin Districts, Karen State: Internally displaced villagers cornered by 40 SPDC Battalions; Food shortages, disease, killings and life on the run,” KHRG, April 2001.

[25] “DEATH SQUADS AND DISPLACEMENT,” KHRG, May 1999; see also “PORTER TESTIMONIES: KAWMOORA REGION,” KHRG, December 1992; “SLORC SHOOTINGS & ARRESTS OF REFUGEES,” KHRG, January 1995.

[26] “Dooplaya Interview: Saw B---, March 2015,” KHRG, November 2016; see also “Nyaunglebin Situation Update: Mone Township, November 2013 to January 2014,” KHRG, July 2014.

[27] “Papun Situation Update: Northern Lu Thaw Township, March to June 2012,” KHRG, September 2012; see also “Nyaunglebin Situation Update: Mone Township, November 2013 to January 2014,” KHRG, July 2014; “Toungoo Interview: Naw A---, January 2015,” KHRG, July 2015.

[28] Source #129; see also “Hpapun Interview: Saw A---, July 2015,” KHRG, April 2017.

[29] Source #168.

[30] Source #94.

[31] “Toungoo Situation Update: Thandaunggyi Township, April to June 2014,” KHRG December 2014; see also source #11.

[32] “Toungoo Situation Update: Thandaunggyi Township, March to July 2015,” KHRG, March 2016.

[33] “Thaton Situation Update: Bilin Township, August to October 2014,” KHRG, April 2015.

[34] Source #50.

[35] Source #165.

[36] “Thaton Situation Update: Thaton Township, July to October 2015,” KHRG, April 2016.

[37] Source #163.

[38] Source #123.

[39] “The clinic was already built and the opening ceremony also was already held but until the present time the lock [on the clinic] has never opened [for the villagers]. There are also no medics or patients. The villagers were mainly talking about that clinic. A villager from Eu--- village said that the clinic looks very beautiful but you cannot use it for anything.” Source #123; see also “Toungoo Situation Update: Thandaunggyi Township, November 2015 to February 2016,” KHRG, November 2016.

[40] “Thaton Situation Update: Thaton Township, April 2014,” KHRG, January 2015.

[41] “Dooplaya Situation Update: Kyonedoe Township, January to June 2014,” KHRG, September 2014; see also

“Thaton Situation Update: Thaton Township, July to October 2015,” KHRG, April 2016; “Toungoo Situation Update: Thandaunggyi Township, November 2015 to February 2016,” KHRG, November 2016.

[42] “Hpa-an Interview: Saw A---, May 2014,” KHRG, May 2015.

[43] For more information see Chapter 6: Development.

[44] KHRG has previously published reports detailing incidents of negative side-effects as a result of elephantiasis vaccine. The KHRG community member could be referring to the incident which occurred between September 9th and 13th 2013, when elephantiasis vaccine was distributed to 1144 villagers from Kawkareik Township by the Myanmar government. Some villagers who received the vaccination experienced dizziness, vomiting, itchy skin, swollen testicles, and even one case of miscarriage. For further details see, “Dooplaya Situation Update: Kyonedoe Township, September to December 2013,” KHRG, September 2014. Similar incidents occurred in other districts. See for example, “Field Report: Thaton District, September 2012 to December 2013,” KHRG, December 2015.

[45] “Dooplaya Situation Update: Kyonedoe and Kawkareik townships, July to November 2014,” KHRG, January 2016.

[46] Source #108.

[47] “Thaton Situation Update: Hpa-an Township, January to June 2014,” KHRG, October 2014; see also “Toungoo Photo Set: Ongoing militarisation and dam building consequences, March to April 2013,” KHRG, February 2014.

[48] Back Pack refers to the Back Pack Health Workers’ Team (BPHWT), an organisation that provides medical treatment for villagers in remote areas.

[49] “Thaton Situation Update: Thaton Township, July to October 2015,” KHRG, April 2016.

[50] “Toungoo district: Civilians displaced by dams, roads, and military control,” KHRG, August 2005; see also “Living conditions for displaced villagers and ongoing abuses in Tenasserim Division,” KHRG, October 2009.

[51] “We do not have clinics in our village but we have midwives and local health workers who know a bit about how to give treatments to sick people. We just get injections from them. If we have serious sickness or diseases, we have to go to [clinics] in Ep--- village to get medical treatment.” Source #170; see also “Toungoo Situation Update: Thandaunggyi Township, July to November 2014,” KHRG, April 2015; see also source #161.

[52] Source #161.

[53] Source #108.

[54] Source #43.

[55] Source #17.

[56] “Toungoo Situation Update: Thandaunggyi Township, January to February 2015,” KHRG, October 2015. KHRG has received several other reports of villagers experiencing negative side effects after taking medicine for elephantiasis provided by the Myanmar government. See for example, “Dooplaya Situation Update: Kyonedoe Township, September to December 2013,” KHRG, September 2014; as well as “Hpa-an Interview: Saw A---, May 2014,” KHRG,May 2014; see also “Hpa-an Interview: Saw U---, December 2013,” KHRG, October 2014; and “Field Report: Thaton District, September 2012 to December 2013,” KHRG, December 2014.

[57] “Hpapun Interview: Saw A---, July 2015,” KHRG, April 2017.

[58] “Toungoo Situation Update: Thandaunggyi Township, June to August 2016,” KHRG, March 2017.

[59] “Toungoo Situation Update: Thandaunggyi Township, April to June 2014,” KHRG, December 2014; “Dooplaya Situation Update: Kyonedoe Township, September to December 2013,” KHRG, September 2014.

[60] Source #94.

[61] Source #18.

[62] “SLORC IN KYA-IN & KAWKAREIK TOWNSHIPS,” KHRG, February 1996.

[63] Source #163.

[64] Source #30; see also “Hpapun Situation Update: Bu Tho Township, February to July 2014,” KHRG, September 2014.

[65] Source #94; see also “Toungoo Situation Update: Thandaunggyi Township, April to June 2014,” KHRG, December 2014; and “Hpapun Situation Update: Dwe Lo Township, May to August 2016,” KHRG, January 2017.

[66] Source #139.

[67] “Thaton Situation Update: Thaton Township, July to October 2015,” KHRG, April 2016.

[68] Sources #30.

[69] “STARVING THEM OUT: Forced Relocations, Killings and the Systematic Starvation of Villagers in Dooplaya District,” KHRG, March 2000.

[70] “UNCERTAINTY, FEAR AND FLIGHT: The Current Human Rights Situation in Eastern Pa’an District,” KHRG, November 1998.

[71] For more information see Chapter 5: Looting, Extortion and Arbitrary Taxation.

[72] “SLORC IN KYA-IN & KAWKAREIK TOWNSHIPS,” KHRG, February 1996; “Achieving Health Equity in Contested Areas of Southeast Myanmar,” The Asia Foundation, June 2016.

[73] “[My most important human right] is health. I have been sick [and not accessed medical care] for around three years, so I cannot work on my farm. Therefore, I have to buy paddy for my family but I do not have money and I do not know where to find money. I am not healthy so I cannot do any job. Moreover, I cannot do anything [to improve my health] without money.” Source #168; see also “On April 13th 1997 my cousin was hurt by the SLORC [Tatmadaw] because for only oneday he’d missed goingfor labour buildingthe houses for SLORC[soldiers’]families.TheSLORChithimwitha gun on his head, above his right ear, and his head was broken. So then the SLORC sent him to the hospital, but they didn’t give any food to feed him in the hospital, and they didn’t even pay the cost of the medicine. They only paid the hospital for the first day. Now my cousin still isn’t healed yet. He said he’ll come here once he heals. His farm and his big house were already taken by the SLORC because his fields are near the SLORC camp.” “ABUSES AND RELOCATIONS IN PA’AN DISTRICT,” KHRG, August 1997.

[74] “Nyaunglebin Interview: U A---, January 2016,” KHRG, February 2017.

[75] “Villagers risk arrest and execution to harvest their crops,” KHRG, December 2007.

[76] “STARVING THEM OUT: Forced Relocations, Killings and the Systematic Starvation of Villagers in Dooplaya District,” KHRG, March 2000; see also “Toungoo Situation Update: Thandaunggyi Township, April to June 2014,” KHRG, December 2014; “Toungoo Situation Update: Thandaunggyi Township, July to November 2014,” KHRG, April 2015.

[77] “Toungoo Situation Update: Thandaunggyi Township, July to November 2014,” KHRG, April 2015.

[78] “Dooplaya Situation Update: Kya In Seik Kyi Township, September 2012,” KHRG, June 2013.

[79] “KAREN HUMAN RIGHTS GROUP INFORMATION UPDATE,” KHRG, February 1999.

[80] Source #175.

[81] Source #6.[82] Source #138.

[83] Source #166.

[84] Source #50.

[85] Source #31.

[86] Source #65.

[87] Source #31.

[88] “KHRG Photo Gallery 2009,” KHRG, July 2009.

[89] “KHRG Photo Gallery 2010: Convict Porters,” KHRG, June 2010.

[90] “PHOTO SET 2000-A,” KHRG, June 2000.

[91] “PHOTO SET 2000-A,” KHRG, June 2000.

[92] “PHOTO DESCRIPTION LIST: SET 94-C MURDERS (THATON DISTRICT), DETENTION (PAPUN DISTRICT),” KHRG, October 1994.

[93] “Dooplaya District: Before the Offensive,” KHRG, May 1997.

[94] “Dooplaya District: Before the Offensive,” KHRG, May 1997.

[95] “The SLORC/SPDC Campaign to Obliterate All Hill Villages inPapun and Eastern Nyaunglebin Districts,” KHRG, February 1998.

[96] “PHOTO DESCRIPTION LIST: SET 94-C MURDERS (THATON DISTRICT), DETENTION (PAPUN DISTRICT),” KHRG, October 1994.