Forced labour is probably the most systematic and prevalent abuse committed by the SPDC against villagers throughout Burma. Village heads are ordered to provide labourers for building roads and other infrastructure, portering for the Army, constructing and maintaining Army camps, performing sentry duty at Army camps and along roads, farming for the Army and many other jobs. In addition, villagers must also use much of their time filling the constant demands from SPDC Army camps and authorities for large quantities of bamboo, roofing thatch, stones and gravel, logs, planks and other materials. Some of these materials are used for the construction and maintenance of roads, SPDC Army camps and other SPDC projects, while the rest is sold on the market for the personal profit of the Army officers. Villagers are not provided with tools or food to complete the work and are often treated brutally, some dying as a result. The labour takes them away from their livelihood and leaves them very little time to farm their fields or to earn a living. Whatever little money the villagers are able to get must be given to the SPDC to avoid having to go for the labour so they can do their own work. Village heads often receive demands from many different Army camps and SPDC authorities for various kinds of labour at the same time. Many villagers try to strike a balance by paying the 'fees' to avoid some of the labour while still regularly going for other forms of forced labour.

Forced labour is probably the most systematic and prevalent abuse committed by the SPDC against villagers throughout Burma. Village heads are ordered to provide labourers for building roads and other infrastructure, portering for the Army, constructing and maintaining Army camps, performing sentry duty at Army camps and along roads, farming for the Army and many other jobs. In addition, villagers must also use much of their time filling the constant demands from SPDC Army camps and authorities for large quantities of bamboo, roofing thatch, stones and gravel, logs, planks and other materials. Some of these materials are used for the construction and maintenance of roads, SPDC Army camps and other SPDC projects, while the rest is sold on the market for the personal profit of the Army officers. Villagers are not provided with tools or food to complete the work and are often treated brutally, some dying as a result. The labour takes them away from their livelihood and leaves them very little time to farm their fields or to earn a living. Whatever little money the villagers are able to get must be given to the SPDC to avoid having to go for the labour so they can do their own work. Village heads often receive demands from many different Army camps and SPDC authorities for various kinds of labour at the same time. Many villagers try to strike a balance by paying the 'fees' to avoid some of the labour while still regularly going for other forms of forced labour.

On November 1st 2000, the SPDC claims to have issued an order outlawing the use of forced labour and prescribing punishment for any soldier, officer or official who continues to demand it. In September 2001 the International Labour Organisation (ILO) sent a High Level Team (HLT) to Burma to evaluate the SPDC's claim. Their findings showed that although the order had been distributed in some areas, its dissemination did not reach many others and forced labour was still widespread. All of the photos in this photo set were taken after the order was issued, most after the HLT's visit. They show that the order and the HLT's critical report have not had much of an effect on the ground.

It is extremely difficult and dangerous to take photos of forced labour, and these here should be seen as a small sampling. For every photo presented here, thousands more could be taken if it was possible to safely do so. The forced labour shown in these photos and described in the captions is consistent with the hundreds of interviews conducted by KHRG throughout Karen areas in 2001 and 2002, and the texts of thousands of SPDC written orders which are sent monthly demanding all forms of forced labour. Some of the interviews can be seen in reports recently issued by KHRG. The translations of several hundred SPDC orders demanding forced labour can be seen in "Forced Labour Orders Since the Ban" (KHRG #2002-01, 8/2/2002), "SPDC & DKBA Orders to Villages: Set 2001-A" (KHRG #2001-02, 18/5/2001) and other previous order sets published by KHRG. See also Photo Set 2001-A and other previous KHRG photo sets and regional reports for additional pictures and information on forced labour.

The photos in this section have been divided into three subtopics: Non-portering , Portering and Convict Porters . Each subtopic contains an explanation of the photos therein.

1) Non-Portering

This section contains photos related to many forms of forced labour, such as digging irrigation canals (Photos # A1 through A5 ), building and maintaining roads and bridges (Photos #A6 and A7, A8 through A11 , and A12 ), and maintaining Army camps (Photos # A13 and A14 , A15 ). There are also many photos involving forced labour cutting bamboo or making thousands of thatch shingles and delivering them to Army camps (Photos # A17 and thereafter). Orders are issued to village heads demanding hundreds or thousands of these at a time. Villagers spend days cutting, processing and delivering them to the Army camps by the deadlines specified in the orders, or the village elders are arrested. They also regularly receive orders to cut and haul logs and planks to Army camps (Photos # A38 and thereafter) under similar conditions. Some of these materials are used for construction (which the villagers are forced to do as well), and some is sold by Army officers and SPDC officials for personal gain. The villagers never receive any compensation for their time or the materials. Logging has been practiced in Karen areas for a long time under the colonial administration and later under the KNU. When the SLORC/ SPDC took over much of the remaining forest area in 1995 and 1997 the officers were quick to learn that they could make huge sums of money selling logs. Demands for logs from villagers rapidly increased and since 1995/97 large areas of Karen State have been deforested.

2) Portering

The use of civilians as forced labour porters by the SPDC Army in rural areas continues to increase as the Army expands and spreads its control to more areas. Villages often receive orders to carry supplies and munitions to outlying Army outposts. When units rotate in and out of these posts, as they do every few months, entire villages are called to carry out the loot of the departing troops and carry in the supplies of the incoming troops. Army columns on operations or patrols often require one porter for every two soldiers or sometimes one or two porters for each soldiers if it is a longer term patrol. For carrying supplies up to army camps the ratio of porters to soldiers can be as high as four or more porters per soldier, a column of 100 soldiers would require up to 400 villagers. In order to get this many people, Army camps send out orders to all surrounding villages to provide several 'permanent porters' on a rotating basis. To supplement this, soldiers routinely grab any villagers they encounter on paths, in fields or in villages and force them to go with the column (see Photos #A61 and A62, A67, A68 and A69). Men often flee the villages when columns are reportedly nearby out of fear of being taken as porters or accused of being supporters of the opposition groups, so the soldiers take the women and children instead. In many rural areas, especially in areas where villages have been displaced and the people are living in hiding, the previous two methods do not guarantee enough porters. To make up the difference, the SPDC has begun rounding up porters in the towns and villages of central Burma, sometimes pressganging men from cinemas and teashops or tricking them through promises of work, especially at railway stations. There has also been a marked increase in the use of convict porters (see 'Convict Porters'). Both these methods were previously used as a prelude to a large offensive, but are now used even for routine operations at the frontline.

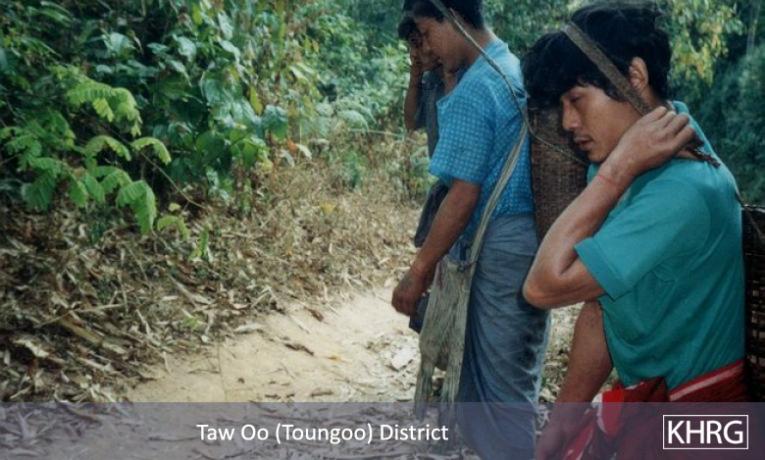

Villagers portering for SPDC Army units are forced to carry loads of up to 40 kilograms (88 pounds) in rough bamboo baskets that rub the skin off their backs, with burlap straps that cut their shoulders open (see Photos #A57 and A69). Villagers who go for a shift of a few days as a 'rotational' porter or carry supplies up to Army outposts for a day are not usually treated too brutally and are able to bring along enough food. Many villagers, however, are ordered to go for one or two days of portering but are then forced to carry for ten or fifteen days. Villagers who are forced to go for longer periods of time or are taken from their houses or fields with no warning are not prepared for the hard labour, abuses, poor diet and sleeping on the ground in the open. They quickly become weak and get sick and begin to fall behind, at which point the soldiers kick them and beat them to 'encourage' them. When a porter reaches the point of exhaustion where he collapses, he is beaten and kicked and then left to die alone on the trail, or sometimes executed. Very little food is provided to porters and medical treatment is almost never given, even to those who are wounded in fighting. Porters are often forced to walk in front and among the soldiers to set off landmines and to discourage ambushes. Villagers wounded by landmines or in ambushes are seldom given medical aid and are usually left on the path or in a village (see Photos #A70, D47 through 50). Villagers, for good reason, view portering as the most feared form of forced labour.

3) Convict Porters

The expansion of the SPDC Army means an increased need for porters, a need that cannot be met by simply forcing villagers, especially in areas where all the villagers are in hiding. The SPDC's answer to the problem is to take more villagers from central Burma and expand the use of convict porters and make it more systematic. This also enables the SPDC to deflect some criticism of its use of villagers for forced labour by claiming that it is using convict labour which is more acceptable internationally. Convicts were often taken from prisons in the past when the Army was about to mount a large offensive and needed to quickly get a large number of porters. In the last few years, however, more and more convict porters have begun to appear with columns on routine operations in Karen areas. They come from prisons as far away as Lashio, Minggyan and Pakkoku. The photos below show just a few of the convicts who have escaped. Their crimes range from 'hiding in the dark' to possession of drugs to theft. No matter the crime, once they are sent to the Army as porters the sentence is the same; work until they escape or die.

It is important to remember that many of the 'convicts' would not even be in a prison in another country. Some of the convicts below were arrested for participating in an illegal lotteries. These small-scale lotteries are common in many countries in Southeast Asia. In neighbouring Thailand the crime amounts to a fine of a few thousand Baht or about a month in jail. Another common 'crime' is 'hiding in the dark', a vague form of conspiracy charge applied randomly to those out at night or even in broad daylight. Other people are arrested on charges of drug possession, even when there is no evidence. Arrests for these and other trivial offences are increasing.

Many of the accused are only kept in the prisons for a few days before being sent to the frontline, while others have been arrested and sent to porter without ever appearing before a judge and officially sentenced. the stories of these convicts raise the serious possibility that many of Burma's poorest citizens are being arrested by SPDC authorities simply to acquire a ready pool of convict labour. Whatever crimes the convicts may or may not have committed, they are still civilians and should not be placed in a potentially life-threatening situation such as portering for a frontline combat unit.

The old practice of sending convicts directly from the prisons to the battalions has been formalised by the creation of various 'Won Saung' or porter-gathering camps. Prisoners are brought from all over Burma to these camps where they are held until an Army unit needs more porters. Won Saung camps have been identified in Pa'an in central Karen State and at Thaton in Mon State. Convict porters are treated much more brutally by the soldiers than villager porters. They are fed very little, given almost no medical treatment, and carry much heavier loads than the villagers. Escaped porters have described conditions which made it apparent to them that they would have been worked to death if they had not fled.

For more information on convicts and forced labour, see the report "Convict Porters" (KHRG #2000-06, 20/12/2000).

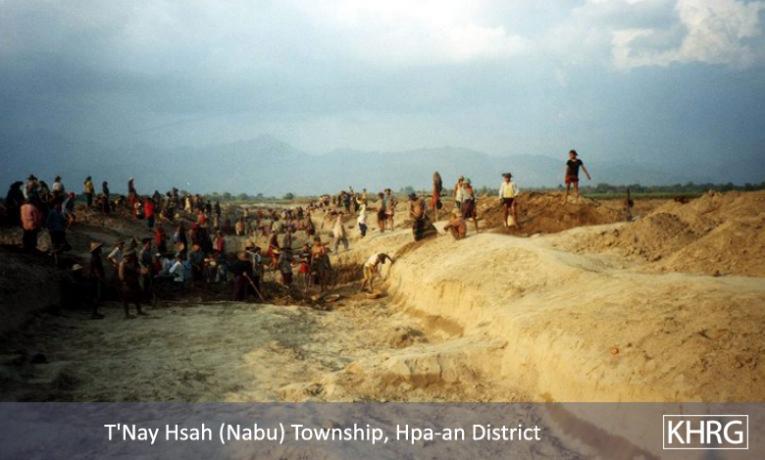

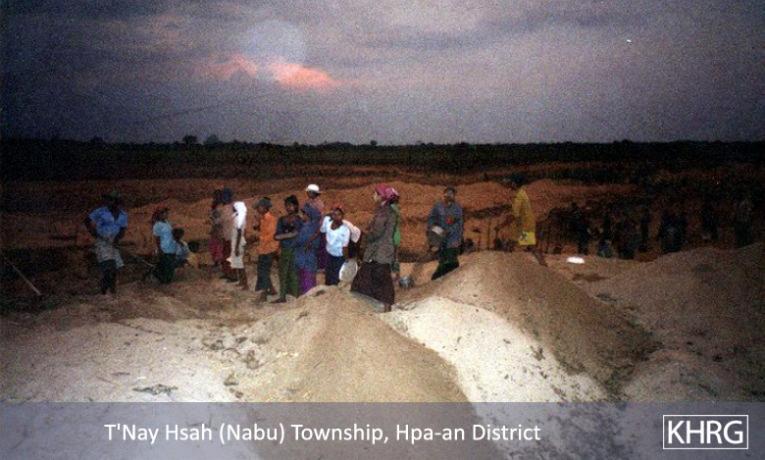

Photos #A1, A2, A3, A4, A5: LIB's #548 and 549 forced villagers from every village tract in T'Nay Hsah township of Pa'an District to begin construction on this canal in January 2002. When these photos were taken in May 2002 the canal was still unfinished. The villagers had to work everyday from 6:00 in the morning until 6:00 in the evening, when it is already getting dark as can be seen in Photo #A5. They had to bring their own rice, water and tools and were paid nothing for the work. Many people became sick from the long hours of work and having to sleep in the open on the ground. In Photo #A1 many of the workers are clearly children, some as young as 12 years old. Children often work alongside the adults in order to get the work over quickly so the villagers can return to their own work. The SPDC never objects to children working as long as the work is done. A KHRG researcher from the area reported that the construction of the canal has resulted in the destruction of at least 30 paddy fields with no compensation paid to the owners. [Photos: KHRG researcher]

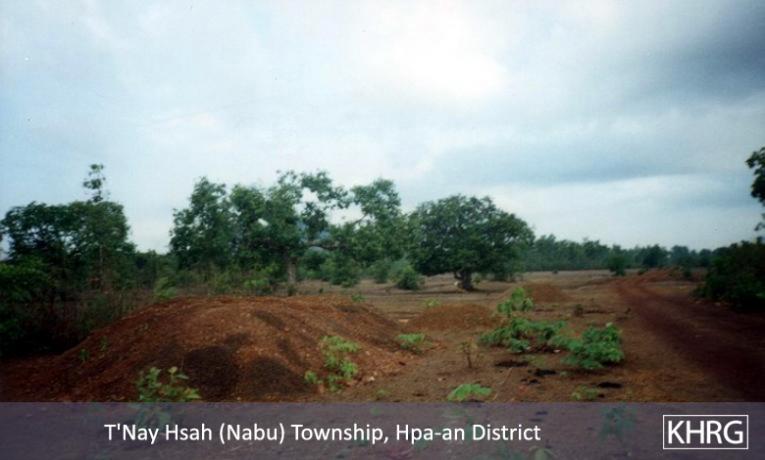

Photos #A6, A7: Villagers from xxxx , yyyy and zzzz villages were ordered by troops from SPDC LIB's #549 and 548 and DKBA #999 Brigade to dig rocks and pile them in kyin alongside this road in T'Nay Hsah township during April 2002. Kyin are piles of rocks which the SPDC will later order the villagers to use to repair the road. [Photos: KHRG researcher]

Photos #A8, A9, A10, A11: This bridge in southeastern Pa'an District cost 2,000,000 Kyat to build. The labour was provided by local villagers working for free, so much of the money probably went into the pockets of Army officers. SPDC soldiers ordered the abbot of the local monastery to build the bridge knowing that the monk would be forced to ask the villagers to do it. The SPDC sometimes orders forced labour in this way in order to displace the blame for the labour onto a monk, or maybe the DKBA, rather than on the SPDC. The abbot told KHRG that he is unhappy about orders like this but he knows he is caught between the KNU, DKBA and SPDC, and must do what he can to get by. When the bridge was completed the SPDC told the villagers that repairs to it are the responsibility of the villagers. A signboard (Photo # A11 ) was erected by the soldiers at one end of the bridge stating: 'This bridge is the bridge of the local civilian villagers. To take care and repair the bridge is always the duty of the civilian villagers.' When these photos were taken the bridge was already beginning to fall apart even though cars have only been using it for a year. Photo #A12: The car road from Kyaikdon to Kya In Seik Gyi in Dooplaya District. Villagers from the villages along its route are often ordered to cut the brush back from the sides of this road to make 'killing zones' and to repair the road. The villagers have to take their own tools and food when going for this work. [Photos: KHRG researcher]

Photos #F26, F27: SPDC soldiers under deputy battalion commander Aung Ko Lay of IB #53 laid landmines throughout the Kaw Thay Der area in early 2002. On on April 2nd 2002 Naw L ---, a 25 year old xxxx villager, was ordered by deputy company commander K --- to cut the brush beside the Kler Lah-Bu Sah Kee road. While she was doing this she stepped on one of the landmines just before noon. Her lower left leg was blown off, her right one was mangled, her hands were injured and she was blinded by the shrapnel. She died at 2 o'clock the same afternoon. The photo was taken the same day. [Photos: KHRG researcher]

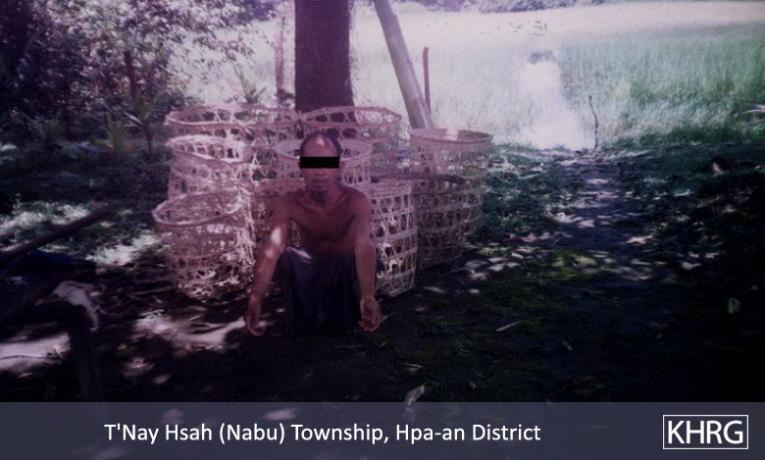

Photos #A13, A14: Villagers in Papun District on their way to make a roof for a food warehouse at Light Infantry Division #66's LIB # xx camp. T he villagers were ordered to do the work by the camp commander. Photo #A15: These seven villagers from xxxx village in Papun District were ordered by LIB # xxx camp commander S--- at xxxx camp to cut 3,000 pieces of bamboo for repairing buildings at the Army camp. Although they had not yet finished cutting the bamboo, they were sent an additional order to go and clear the brush from beside the Papun-Ka Ma Maung road. One person from each house had to go to clear the brush. Photo #A16: Baskets woven by villagers in T'Nay Hsah township of Pa'an District under the orders of SPDC soldiers. Villagers are often ordered to weave baskets which are then often used for the loads of porters carrying for the soldiers. The villagers are never paid for the materials or the work. Photo #A17: Villagers from xxxx village, Pa'an District, carrying the five pieces of bamboo and two chickens demanded by a local SPDC Army unit. Village heads often receive orders demanding building materials and that chickens or pigs be sent along for the soldiers' dinner. Money is almost n ever paid by the soldiers either for the building materials or for the pigs or poultry. Photo #A18: Stacks of thatch which villagers from xxxx village in Papun District were ordered by the DKBA to gather along the banks of the Bilin River. The thatch will probably be taken downriver by the DKBA who will either use it for their own homes or sell it. [Photos: KHRG researcher]

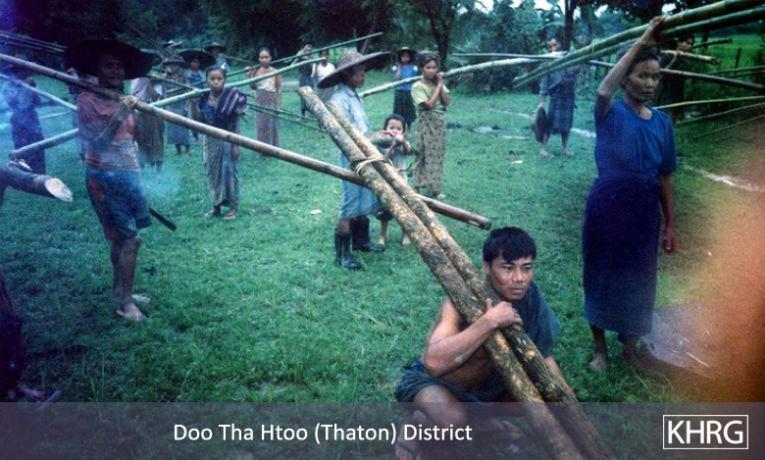

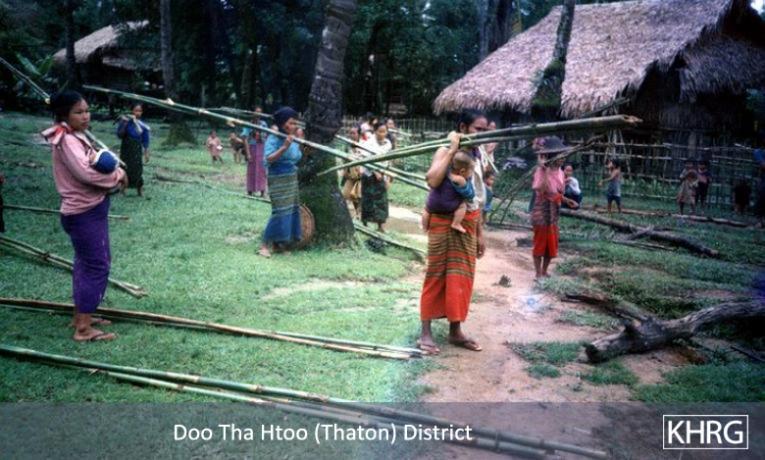

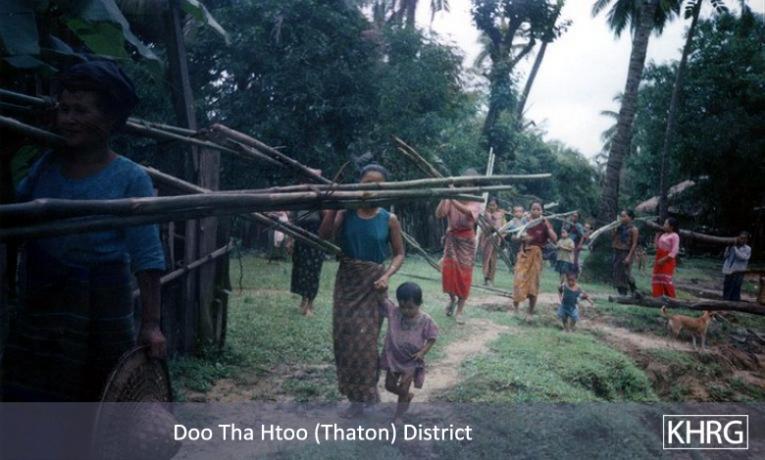

Photos #A19, A20, A21, A22, A23, A24: In late August 2001, Battalion Commander aaaa of IB # xxx at yyyy Army camp in Thaton District ordered the xxxx village head and villagers to cut bamboo and bring it to the Army camp. Each village in the area had to send 200 lengths of bamboo. Photos #A23 and A24 show the bamboo being loaded into boats to be sent downriver to the Army camp. Note the number of small children in Photos #A21 and A22. Women often have to bring their children along with them because there is no one else to watch them with the men and other children either in the fields or performing some other forced labour. [Photos: KHRG researcher]

Photos #A25, A26: In early March 2002, xxxx villagers in Papun District were ordered by camp commander aaaa to send the thatch that they had been ordered to make to LIB # xx , LID #66's camp. The se photos were taken while the villagers were taking the thatch to the Army camp. [Photos: KHRG researcher]

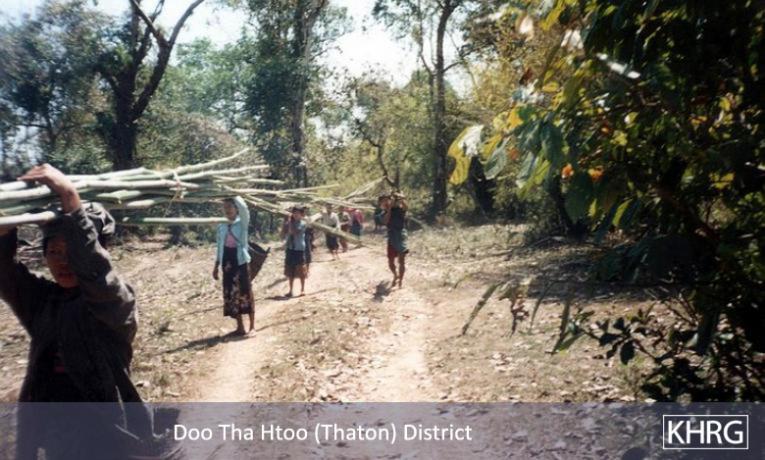

Photos #A27, A28, A29, A30, A31: Villagers in Thaton District go to carry thatch and bamboo to a nearby SPDC Army camp. Villagers in Thaton District told KHRG researchers that units of LID #44 came to make their camp at xxxx village in early 2002 and have forced the villagers to do a lot of forced labour. They have to make fences, cut the brush beside the car road and to send thatch, bamboo and logs to the Army camp. The villagers have to go w henever the SPDC sends orders to the them, or they will no longer be able to stay in their villages. In Photos #A27 and A28 the villagers are carrying thatch to the Army camp. In Photo # A29 a villager cuts bamboo for the soldiers and Photos #A30 and A31 show villagers carrying the cut bamboo to xxxx Army camp. [Photos: KHRG researcher]

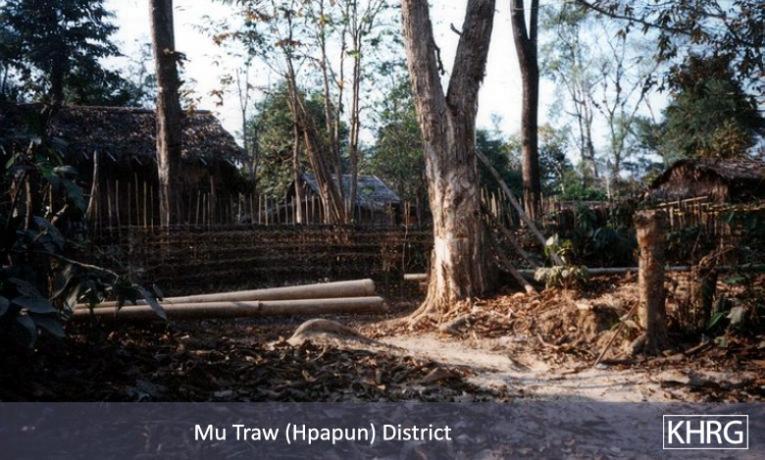

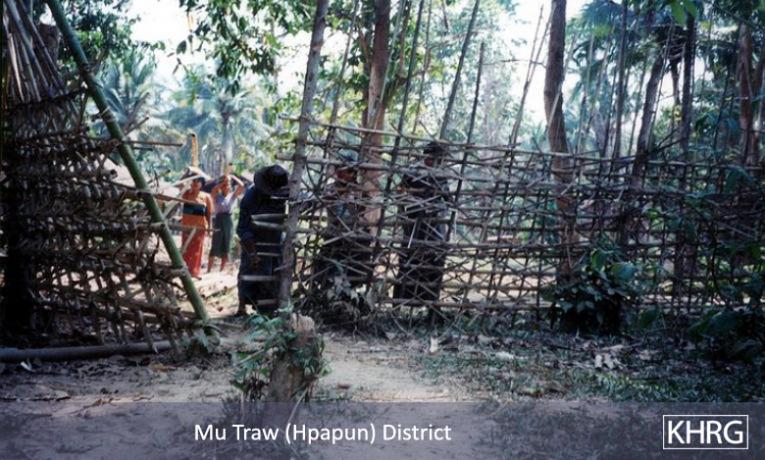

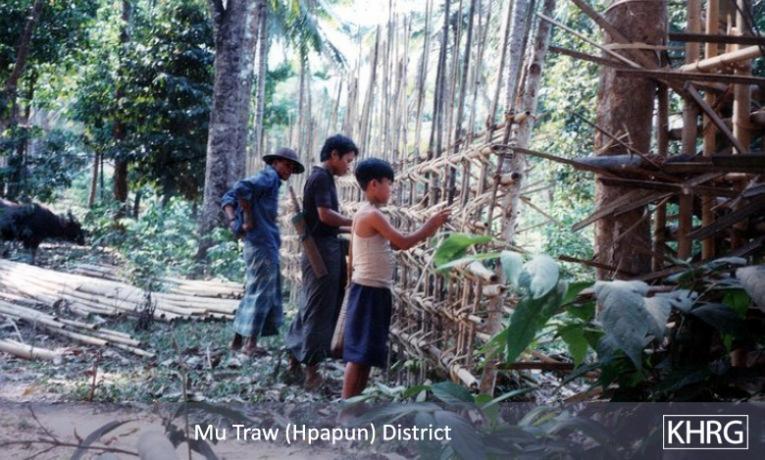

Photos #A32, A33, A34, A35, A36, A37: In late February and early March 2002, the Camp Commander of LID #66's LIB # xxx camp at xxxx village in Papun District ordered the villagers of yyyy , zzzz , uuuu and vvvv to fence their villages. The villages had to be entirely fenced in with only one or two exits allowed. The fences are supposed to keep opposition groups out of the villages as well as making it easier for the soldiers to round up forced labourers when they come to villages. [Photos: KHRG researcher]

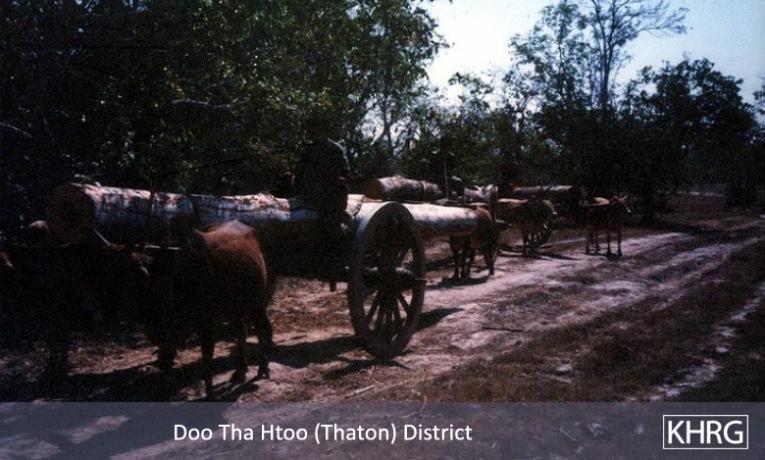

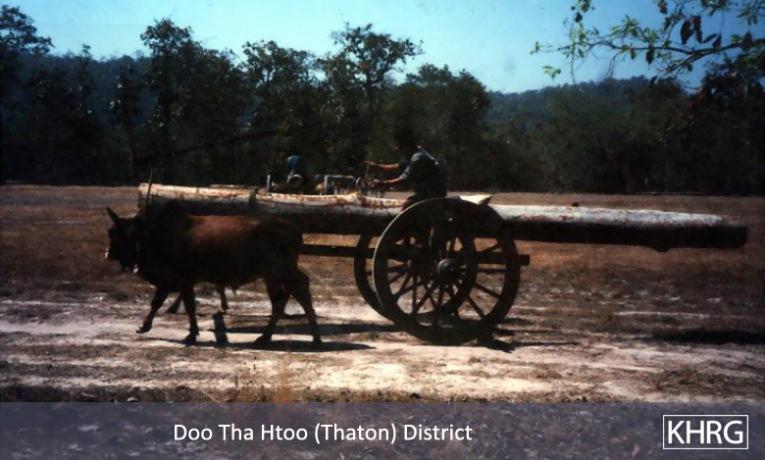

Photos #A38, A39: Photo #A38 shows an order letter and 9mm bullet sent by Battalion Commander aaaa of LIB # xxx at xxxx village in Dooplaya District in December 2001. The letter was sent to the yyyy village headwoman and demands planks of wood to be cut and delivered to the Army camp. The bullet was included in the envelope as a very direct threat. The village headwoman did not dare to go, so a few days later LIB # xxx sent another letter and ordered the yyyy village sawmill owner to make the planks. A list of dimensions for the planks was included and t he order stipulated that the planks be sent to zzzz town by late December 2001. Photo # A39 is of the sawmill. Photos #A40, A41, A42: SPDC soldiers in Thaton District demanded logs from xxxx and yyyy villages in mid-2002. After cutting them the villagers had to carry the logs by bullock cart to the SPDC Army camp at zzzz on the bank of the Salween River. The SPDC paid nothing for the logs or the use of the bullock carts, but the villagers would not have been able to remain in their villages if they did not cut and deliver the logs. [Photos: KHRG researcher]

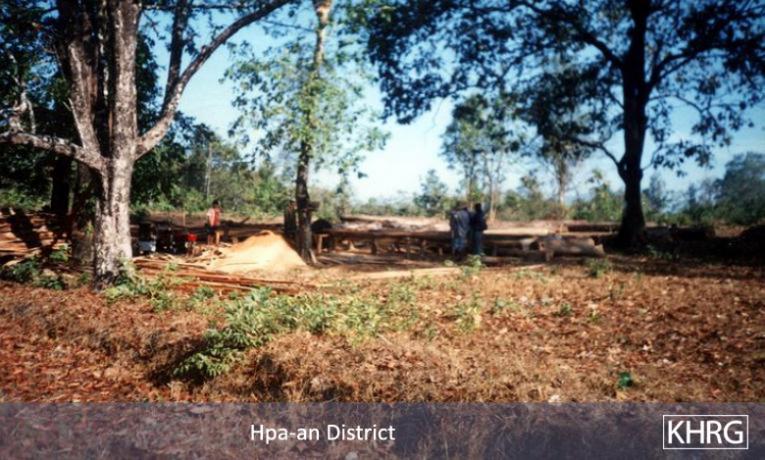

Photo #A43: Logs cut for SPDC soldiers from xxxx Army camp by local villagers lie on the bank of the Play Loh River in Nyaunglebin District in late 2001. The logs will be sold by the soldiers for their personal profit. Photo #A44: Trees which have been cut down but not yet processed by the DKBA at xxxx village in Pa'an District. The DKBA take the dried trunks, process them and u se them as housing materials. A researcher from the area reported that there are many of these logs but no more standing big teak trees in the area anymore. When the DKBA formed in 1995 they were allowed by the then SLORC to do logging in the area. A KHRG researcher from the area reported that so much logging has been done in the area since 1995 that t he remaining trees are more than 3 feet in circumference. Trees that have stood in the area since the time of British colonial rule have now all been cut down. T he villagers are upset because the ir forests have been destroyed and the SPDC and the DKBA are getting the profits from selling the wood. One result of the logging is that the water in the streams and ponds around the villages now drie s up in the hot season, making it difficult for them to grow a dry season crop or find water for drinking and washing. The villagers are unable to do anything to protect the trees and t he KNU can no longer look after the trees as they did in the past under their more controlled logging practices. Photos #A45, A46: Villagers in xxxx village, southeast Pa'an District saw cut logs into planks. After the wood is cut into planks it is then sent into town to be sold. The work was ordered by the DKBA who were in turn ordered to do it by the SPDC. SPDC units often issue their orders through the DKBA so that if the villagers are unhappy with the logging then it appears as the DKBA's fault and not that of the SPDC. If the KNU tries to stop the villagers cutting the trees, the DKBA causes problems for the villagers because the DKBA is also getting a cut of the profits from the trade. [Photos: KHRG researcher]

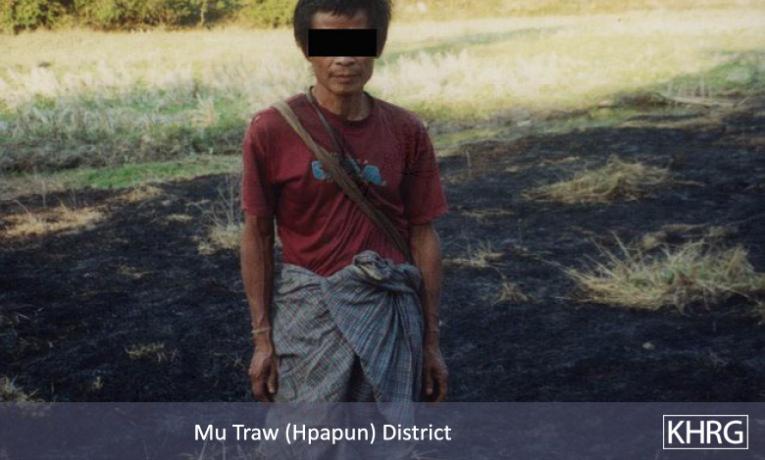

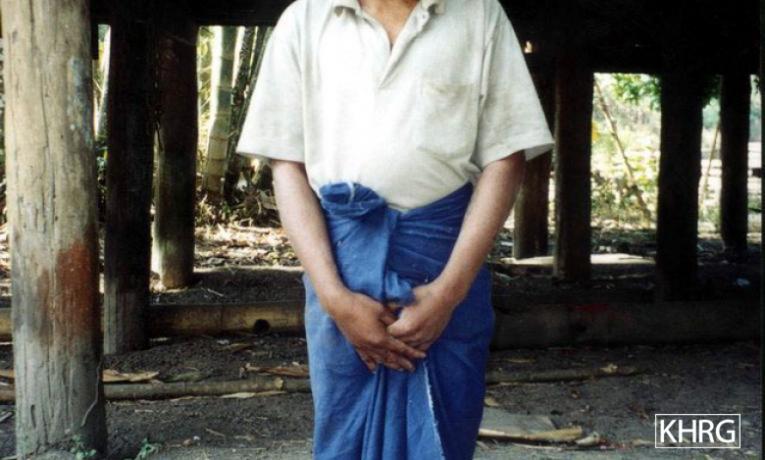

Photo #A47: Logs in a forest in Kya In township of Dooplaya District cut down by the timber company of aaaa and bbbb , two men who are members of c ease-fire group. Companies such as this are cutting down much of the forests in the area. The logging is done indiscriminately with no conservation or replanting. The villagers do not like the logging and receive no profit from it, but they are unable to stop the logging and have no say in which trees can or cannot be cut down. Photo #A48: One of the trucks which the SPDC is using to do logging in the area of xxxx village in Thaton District. The villagers in the area receive no profits from the logging operations but they have to go and cut the brush along the sides of the car road from yyyy to zzzz so that the SPDC can use it to transport logs along it. Photo #A49: Stacks of bricks belonging to DKBA #999 Brigade at their camp at xxxx in Pa'an District . Villagers from yyyy , zzzz and vvvv villages were forced to make the bricks which were then used by the DKBA or sold for the DKBA's profit. The villagers were not paid for this work nor did they receive any of the profits. Photo #A50: Saw aaaa is a 51 year old married Karen animist hill field farmer from xxxx village in eastern Papun District. SPDC commander bbbb of LIB # xxx based in Papun came to his village in mid-January 2002 and ordered the villagers to go for set tha [messenger] and sentry duty at Papun. He also decreed that from that day villagers will have to go once a week, every week, for the same work and their village would be relocated if they d id not go. Saw aaaa said that a ll the other villages close to xxxx have been given the same orders. [Photos: KHRG researcher]

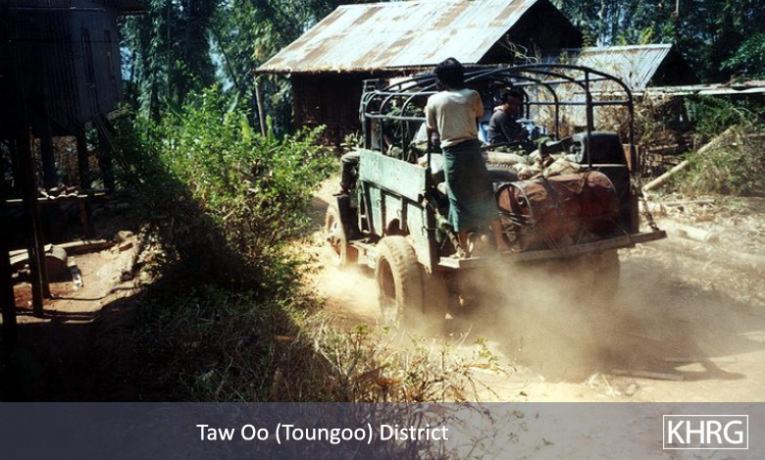

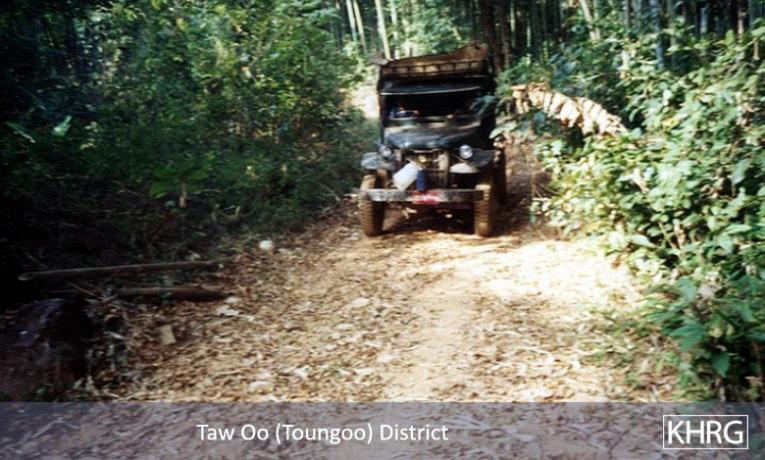

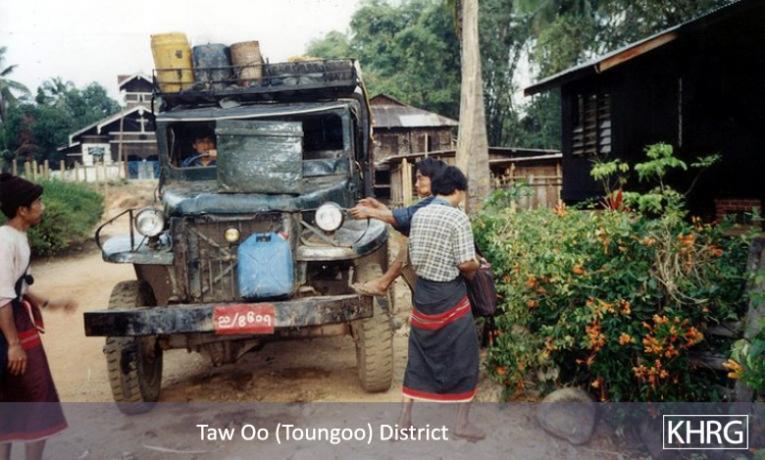

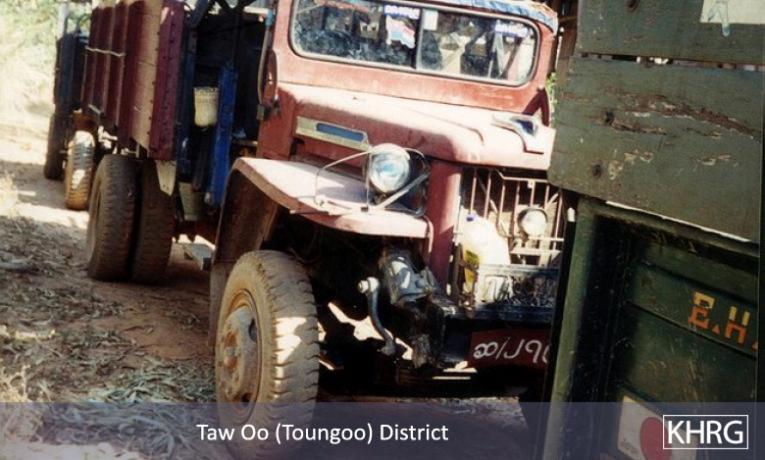

Photos A51, A52, A53, A54, A55: The SPDC ordered the drivers of these seven trucks to carry their supplies and provisions on the Kler Lah-Bu Sah Kee car road in Toungoo District in March 2002. The trucks belong to drivers who operate transportation services along the Toungoo-Kler Lah road, but for this work they are not compensated by the SPDC for their time or the gasoline. The commandeering of their vehicles means that the drivers will be unable to make any money from transporting people and goods along their normal route. T his road is also known to be heavily mined and the drivers fear running over one of the mines. The SPDC often uses trucks along the road in the dry season to transport their supplies, although villagers must still go with the trucks to load and unload them. When the rains begin again and the road becomes impassable, villager porters will be used instead. [Photos: KHRG researcher]

Photo #C17: In July 2002, SPDC soldiers of LIB # xxx under Column Commander T--- and DKBA soldiers of #555 Brigade under M--- arrested Saw Y---, 57 years old, in the fields near his village in Pa'an District and forced him to show them where the KNLA was staying. When they arrived at yyyy in the forest he said, "I do not dare to go any further." He thought that because they were near to a KNLA place there would be many landmines and he was afraid. At that point Commander T--- hit him on the head with a gun butt until he fell unconscious. When he came to again the soldiers were eating rice and not watching him so he ran away. The blood from the wounds on his head from the beating are clearly visible on his face and shirt. [Photo: KHRG researcher]

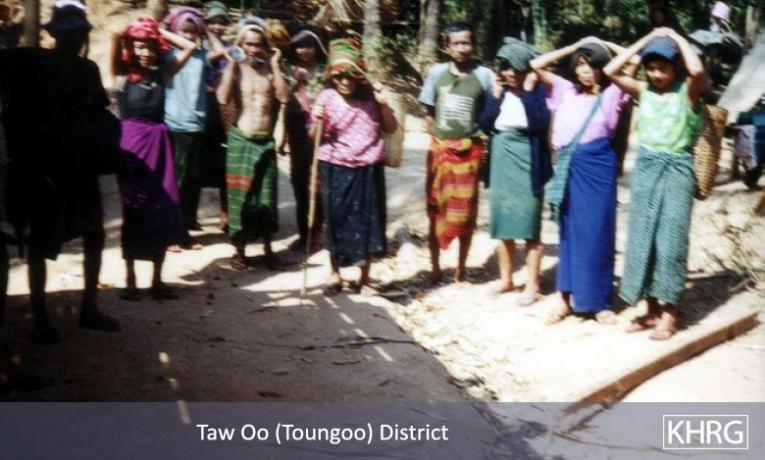

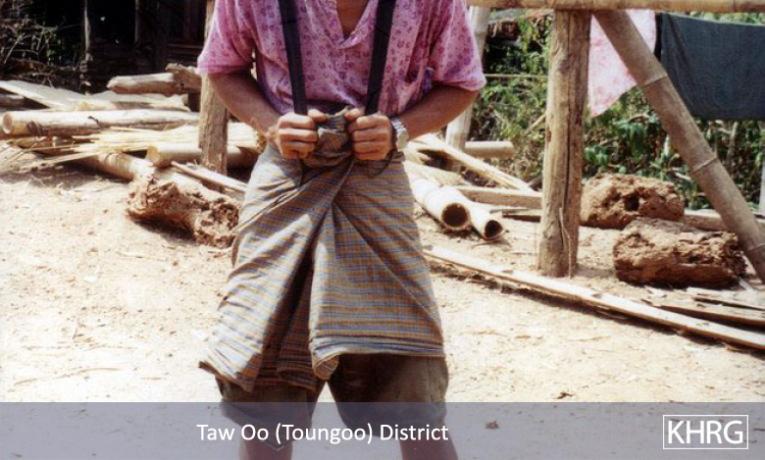

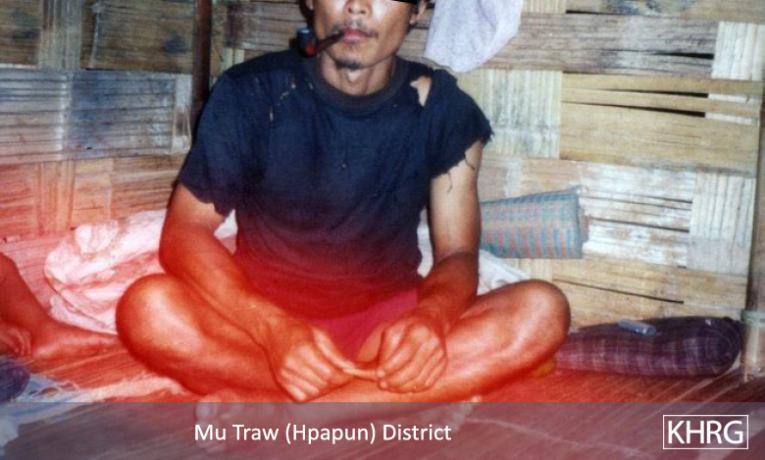

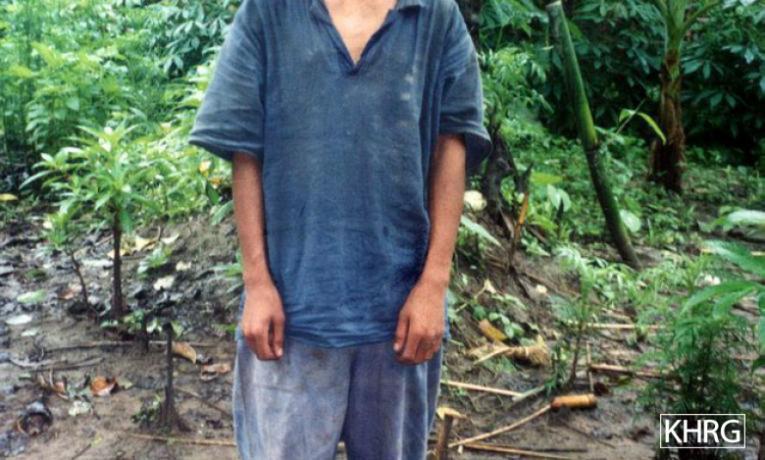

Photo #A56: Saw G ---, a villager from xxxx village, fled from LIB # xxx led by Commander aaaa after they beat him when he was portering for their column. Porters are commonly punched, kicked and hit with rifle butts if they are too slow or unable to carry the loads. Photo #A57: A villager from xxxx village in Dooplaya District shows the place where his shoulder was worn r aw by the basket he had to carry when he portered for IB # xxx in mid-December 2001. This photo was taken four days later. Photos #A58, A59: Villagers in Toungoo District before going to porter for the SPDC on the Kler Lah-Bu Sah Kee car road in March 2002. Villagers in this area are forced to porter supplies for the SPDC Army down this road in both the rainy and the dry seasons. Villagers are routinely forced to walk in front of the soldiers along this road as human mine sweepers and t he road has become notorious for the number of villagers who have been killed or maimed by landmines while portering along it. Photo #A60: Saw S---, a villager from xxxx village, escaped from LIB # xx , LID #44 in early February 2002 after being forced to porter for them in Papun District. He fled because he could no longer carry his load. [Photos: KHRG researcher]

Photos #A61, A62: When LID 66 troops rotated out of xxxx camp in Papun District in early April 2002, the new commander who was rotating in ordered the people of four villages to carry in the rations for the incoming troops. Photo #A63: Saw T---, 40 years old, demonstrates how he has to carry loads as a porter for the SPDC Army. This photo was taken in mid-March 2002, nine days previously, he had to carry rice to xxxx Army camp for the SPDC. In early March 2002, SPDC soldiers under Major aaaa of IB #xx took Saw T---'s possessions worth 20,000 Kyat. He is a farmer with seven children in yyyy village, Toungoo District. Photos #A64, A65: Naw K--- (Photo #A64) and Naw L--- (Photo #A65) have to carry rice to xxxx army camp in Toungoo District whenever Commander aaaa of the Southern Command's Strategic Operations Command #3 orders them to do so. They are both from yyyy village. Naw K--- is 12 years old and Naw L--- is 17 years old. Women and children are often among the villagers who have to porter supplies to SPDC Army camps along the Kler Lah-Bu Sah Kee road. Photo #A66: Saw S--- is a 53 year old villager from xxxx village in Toungoo District. In mid-June 2001, one of his daughters was forced to porter for a IB #xx. Fighting broke out and she was killed. The SPDC did not allow Saw S--- to take his daughter’s dead body back home and he was unable to see his dead daughter’s body before she was buried. [Photos: KHRG]

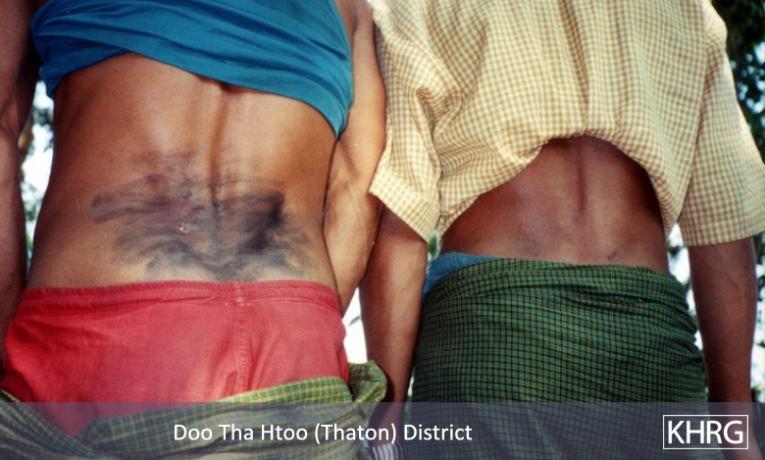

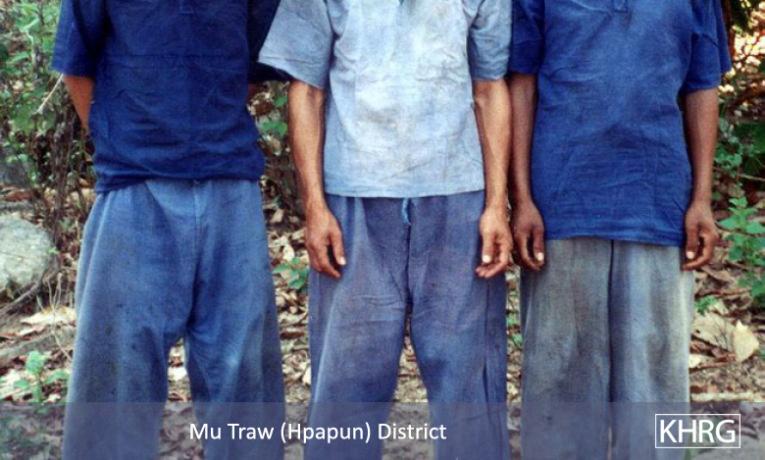

Photo #A67: Villagers from xxxx village, Thaton District, who had to go and porter for LIB #xxx, LID #44 under Battalion Deputy Commander aaaa. In early March 2002, the soldiers entered xxxx village and demanded 12 villagers to go and porter for them to yyyy village. The porters were not fed any rice and had to carry loads of about 25 viss [40 kgs. / 90 lbs.]. Photos #A68, A69: These eight men from xxxx village, Thaton District, were among 13 villagers forced to porter for Lieutenant aaaa and 30 soldiers of LIB #xxx, LID #44 in early March 2002. the villagers were forced to carry army rations and bullets. Photo #A69 was taken four days later and the wounds from the rubbing of the rough bamboo baskets can still be seen on their lower backs. [Photos: KHRG]

Photo #A70: Naw D--- lives in xxxx village, eastern Papun District. She is a 27 year old married Karen Buddhist hill field farmer. SPDC troops of LIB #xx, LID #xx came to her village in early March 2002 and took the villagers’ belongings. They also took Naw D---'s husband and forced him to porter for them for two days. He stepped on a landmine while portering. He was not given any medical treatment by the SPDC soldiers. Photo #C5: Saw P---, a 36 year old farmer from xxxx village, eastern Papun District, was arrested by SPDC soldiers in February 2002 when he was going to look after his buffaloes in his flat field. The soldiers accused him of being a KNU spy. They bound his hands and neck and forced him to porter for them. They also went to his hut and took 20 baskets [500 kgs. / 1,100 lbs.] of paddy and 10 chickens. The soldiers intended to kill Saw P--- but he was eventually able to escape. Photo #D39, D40: Saw M---'s (Photo #D39) wife was shot dead by a combined column of LIB #115 and IB #17. She died in the hill fields near H--- village, Papun District, in on July 25th2001 at 1:30 in the afternoon. Saw M--- was arrested, bound and forced to carry as a porter for the soldiers for one month before they released him. Photo #D40 is of Saw M---'s fourchildren who he must now take care of without his wife. [Photos: KHRG]

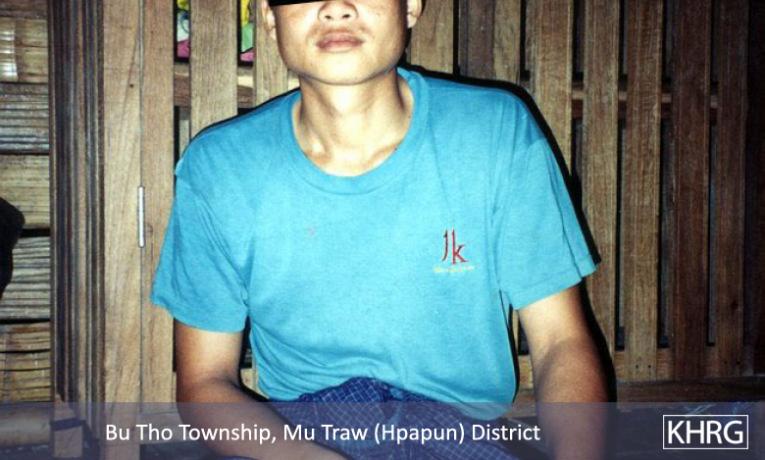

Photo #D41: Saw L--- was taken by SPDC soldiers as a porter in Pa’an District in late 2001. When he later ran to escape, the soldiers shot at him and he was injured in the right forearm. Photo #F35: Saw A---, 30 years old, is a villager from xxxx village in Bu Tho township of Papun District. Column #1 of LIB #102 came to his village and forced him to go as a porter, and on March 1st 2002, he stepped on a landmine near yyyy village in Papun District. The soldiers left him under a house with one of his friends and continued on. After three days, patrolling KNLA soldiers found them and took him to a clinic. This photo was taken on June 26th 2002. [Photos: KHRG]

Photos #D47, D48, D49, D50: Saw H--- and Saw P--- from xxxx village were taken as porters by LIB #xxx, Battalion Commander K---, in Dooplaya District. Fighting occurred along the way. Saw H--- (Photos #D47, D48), 47 years old, was seriously wounded. Although he was wounded while portering for the SPDC he received no medical attention from SPDC medics in these photos but from KNLA medics or a mobile medical team. Saw P--- (Photos #D49, D50), 56 years old, was less seriously injured. This photo was taken on December 24th 2001. [Photos: KHRG]

Photo #E107: On February 20th 2002, SPDC soldiers of LIB #xx under Battalion Commander T--- entered L--- village in Thaton District at five in the evening in search of villagers to take along as forced labour porters. All the single men in the village fled to avoid being taken as porters. [Photo: KHRG]

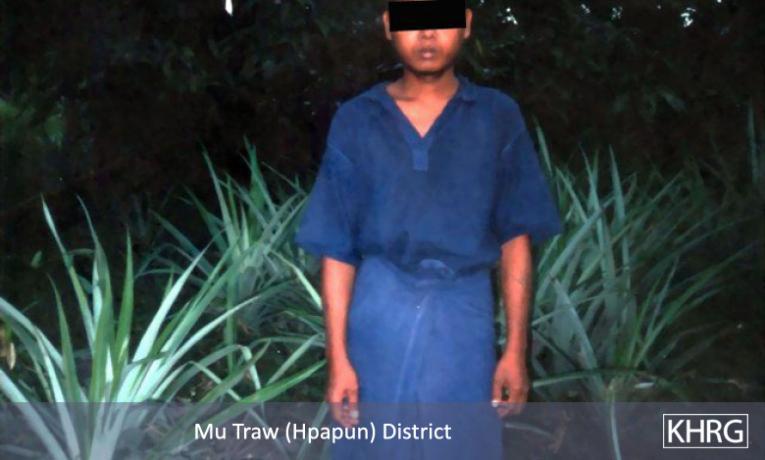

Photo #A71: Saw T---, 20 years old, is a farmer from xxxx town, Pegu Division. He was arrested by the Army in Pegu town along with nine others when he went to buy food. The soldiers stole his two gold necklaces and then forced him to porter for LIB #xx from Ler Doh to Ler Mu Plaw in northern Papun District. He told KHRG researchers that there were 200 convict porters and 100 villagers carrying for the column. The soldiers forced the villagers to immediately put on the distinctive blue convict’s uniform so they would look like the other prisoners. He saw four porters, both Karen and Burman, die from abuse along the way. After carrying a 20 viss [32 kgs / 72 lbs] load for six days he fled the column in April 2001. [Photo: KHRG]

Photo #A72: T---, 18 years old, from xxxx township, Rangoon Division was sent to Insein Prison in February 1999 for stealing. The police arrested his uncle for stealing a car and the uncle said that he had shared the money with T---. Although T--- told the judge he never received any money, he could not find anyone to vouch for him so he was sentenced to two years in prison. In 2001 he and about 300 other convicts were sent as porters to LIBs #545, 547 and 355 under Major Kan Cho in Dooplaya District. He told KHRG that he had to carry shells and rice for the soldiers. The load was about 20 viss [32 kgs / 72 lbs]. He witnessed convicts being reviled, kicked and punched by the soldiers for not being able to walk and carry their loads and experienced it himself. At meal times they were fed only one plateful of rice, salt and water. The convicts were threatened with being shot by the soldiers if they tried to flee. By the time he fled only 20 convicts were still with the column. Some of the others had died during fighting between the SPDC and the KNLA, while others had fled or died of disease and mistreatment. Eventually he fled because he could no longer carry his load which had become heavier and heavier as he became weaker. [Photo: KHRG]

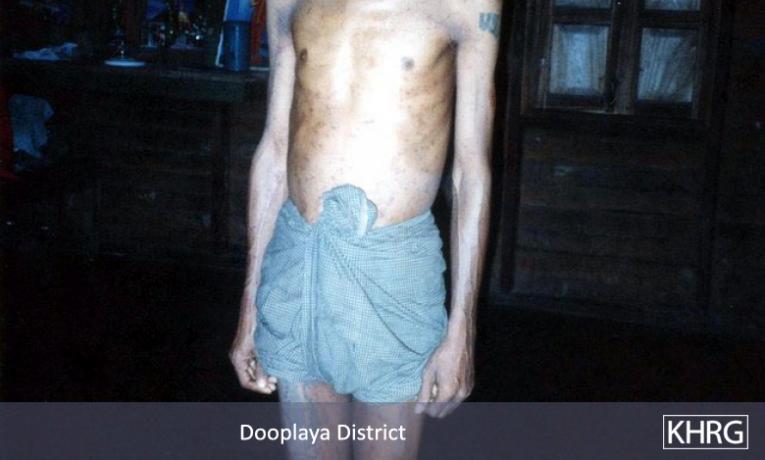

Photos #A73, A74, A75: M--- is a 42 year old Burman convict porter from Rangoon Division. Arrested in September 2000 and sentenced in January 2001 to two years in Insein Prison for theft, he was sent to Pa’an Won Saung Battalion #2 five months later. “When we were in the prison they [the SPDC] came to the prison and called out the names and numbers of the prisoners. The next morning we had to go out and stand in a line. They issued us two pairs of prisoner uniforms and one plastic cup. They were blue coloured. After they issued us that they told us to be ready and the next morning they came and took us by truck. They told us, ‘You have to go to the Won Saung and you have to go with the Army unit.'” He was forced to porter for LIBs #547, 548 and 549 in Dooplaya District. The soldiers forced the convicts to carry rations, shells and other material. Eventually he could no longer carry his load because his legs had become swollen and his feet were blistered. When he could no longer walk, the soldiers surrounded him, poked him with their guns and kicked him with their boots. One of his molars on the right side was broken during the beating. When he fell unconscious they left him in the forest. Note his emaciated condition in Photo #A75. [Photos: KHRG]

Photos #D28, D29: When the villagers of xxxx village, Papun District returned to their village on November 30th 2001, they found a convict porter lying dead on the paddy in Saw N---’s hut. The porter had been carrying for Tactical Operations Command #333, LID #33. When a KHRG researcher saw him, the porter looked as though he had been kicked repeatedly because his side was very bruised and his face looked as though it had been punched multiple times because it was swollen in many places. The sole of his foot was burned and had burst. A few chillies were found beside him and the villagers thought that he may have eaten them because he was so hungry before he died. By the time he was found he had been dead for three days. [Photos: KHRG]

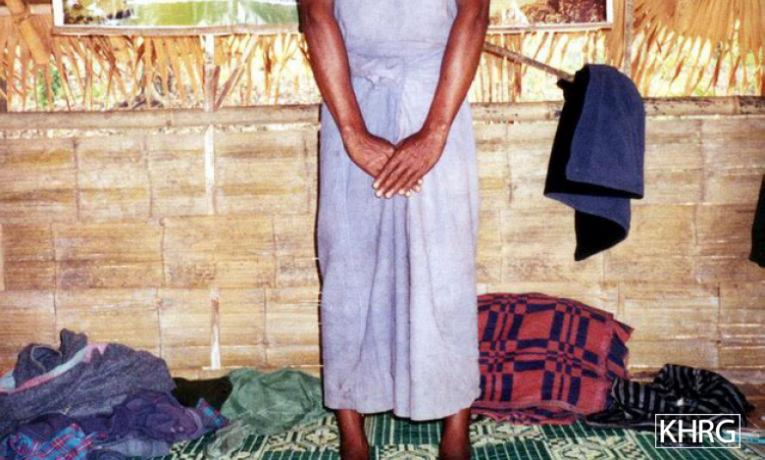

Photo #A76: P---, a 27 year old Karen farmer from xxxx village in Irrawaddy Division, was arrested and put in prison for drinking alcohol and returning home at night. He was then sent to an Army unit in Nyaunglebin District as a convict porter. He was later able to flee. Photo #A77: These six convict porters escaped from Tactical Operations Command #333, LID #33 in early December 2001. They no longer had any food when they fled and were unable to walk. They are T---, 25 years old, W---, 23 years old, S---, 30 years old, M---, 35 years old, T---, 30 years old and K---, 22 years old. Some of them had to porter for two months and some for one month before they fled. They all had to carry loads of about 20 viss [32 kgs / 72 lbs]. They fled because they could no longer carry the loads. The soldiers had only fed the porters rice with a little salt in it. Some of the porters had malaria and some had pains in their chests and were vomiting blood because the SPDC soldiers had kicked them and stomped on them. All six porters said that many other porters had been killed. [Photos: KHRG]

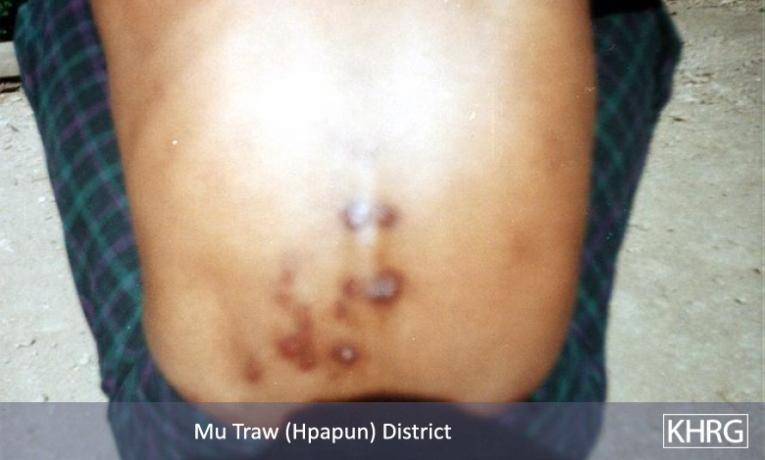

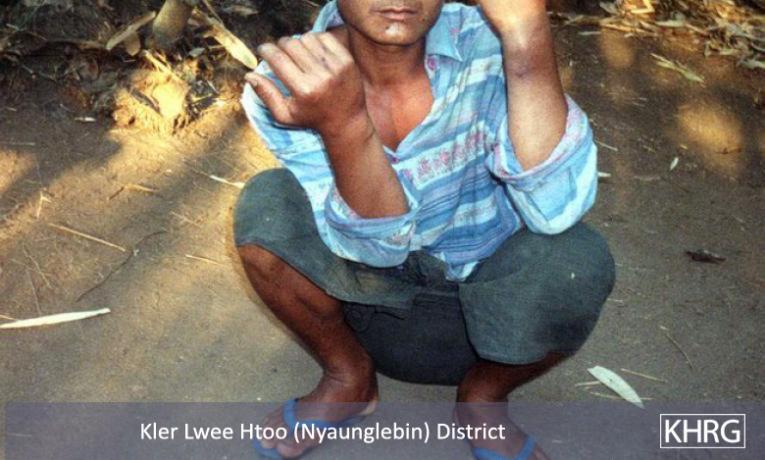

Photos #A78, A79, A80: T---, an 18 year old Burman from Irrawaddy Division, fled from the SPDC column he was carrying for as a convict porter in Papun District. He had gone fishing with his friends in the evening and was arrested because he was carrying a knife. He was then sent to a local military police office and then to Henzada Prison for three months. After being taken from the prison he was first sent to Toungoo and then came down to Shwegyin in Nyaunglebin District with LID #33. He portered for a combined column of IBs #4 and 76 and LIB #111. While carrying for them he was beaten nearly to death. He was hit on his backbone by the barrel of a gun. The wounds on his back, shoulder and head are clearly visible in photos #A78 and A79. He could not endure it anymore and fled when the column left Lay Wah village after burning it. He was still ill from his experience when these photos were taken. [Photos: KHRG]

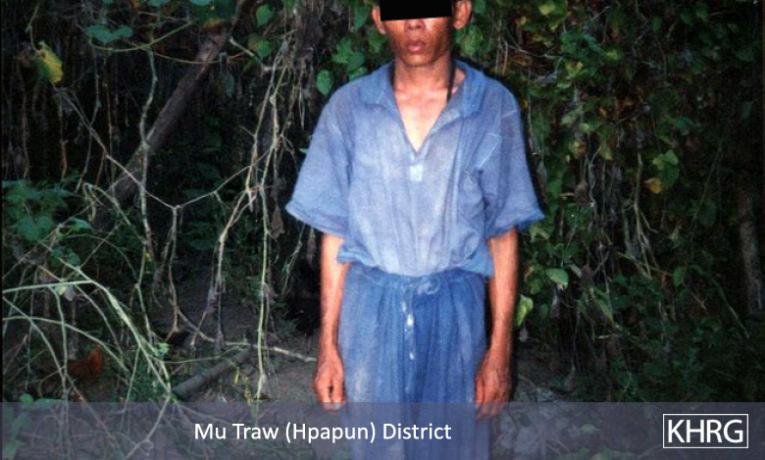

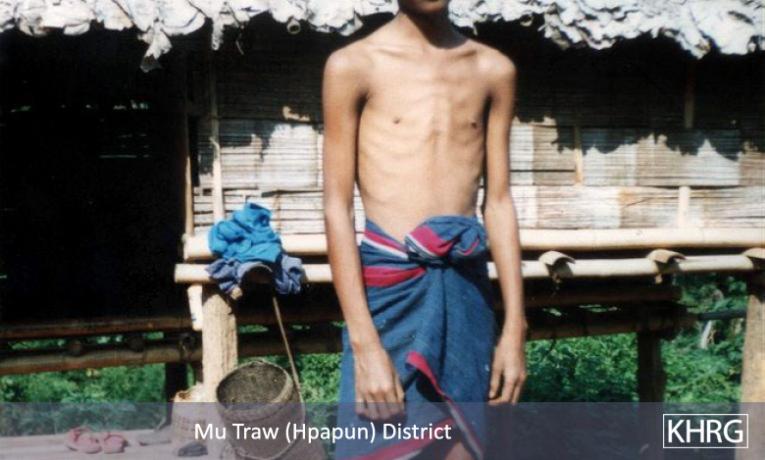

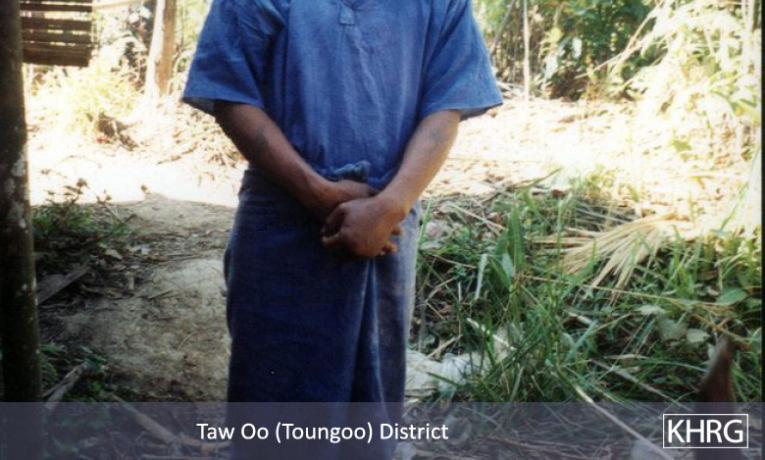

Photos #A81, A82: This convict porter, Z---, ran away from the SPDC column he was carrying for in Papun District when he could no longer endure the treatment. He has many woundsfrom the brutal treatment he received from the soldiers. The soldiers kicked him in the mouth causing him to lose two of his teeth. They also burned his neck and leg with fire (see Photo #A82 of his leg). Photos #A83, A84: SPDC porters who ran away from the column they were carrying for in Papun District. M--- (photo #A83) is a married Burman merchant from xxxx, Irrawaddy Division. T--- is a 30 year old married Burman farmer from xxxx, central Burma. Photos #A85, A86: M---, a convict porter, escaped from the SPDC Army column that he had been forced to porter for in Papun District in late 2001. Photo #A86 shows the wounds on his back from the rubbing of the basket he had to carry. Photo #A87: Z--- told a KHRG researcher that he ran away from the SPDC column he was forced to porter for in Papun District because he knew that if he continued he would die. He was almost dead when he was found by KNLA soldiers in the forest. He told them he had only the one life his mother gave him and that is why he ran away. This photo clearly shows his emaciated condition brought on by exhaustion, disease and poor diet. [Photos: KHRG]

Photos #D51, D52: This convict porter was found dead near Kyauk Tan village in Dooplaya District, about 15 metres from a path. He was apparently beaten to death by soldiers of LIB #546 under Column #1 Commander Kin Maung Yi on December 23rd 2001. His name is unknown. This photo was taken on December 30th 2001. Photo #A88: K--- is a 20 year Burman from xxxx village in central Burma. He was making jade bracelets when he was arrested and put in prison. He was then forced to porter for LIB #306. He ran away in Toungoo District in February 2002. He wandered for eight days before meeting KNLA soldiers. His health is no longer very good. When this photo was taken he was receiving treatment for gastritis, malaria, Hepatitis B and Edema. When he was found after running from the soldiers he could only eat dried fish and gram. This photo was taken on February 10th 2002. Photo #A89: These five convict porters escaped in early 2002 in Toungoo District. [Photos: KHRG]

Photo #D60: The skulls and bones of two convict porters found by villagers in November 2000 in Saw Htee township of Nyaunglebin District. The porters were wearing the white sarongs of convict porters and had been carrying for LIB #367 and 368 commanded by Lt. Col. Ko Ko Aung. The lower left portion of the skull of one of the porters was destroyed suggesting that he was beaten to death. Knife marks were also found on a shin bone suggesting torture. The other body was unmarked. Villagers who found them before they had decomposed said that one of the bodies looked as though it had been beaten to death and the other was unmarked and had probably died of exhaustion or illness. [Photo: FBR]

Photo #A90: S--- was arrested on a train while selling snacks to the passengers. The police demanded money from him, but he could not pay so he was arrested. He was later sent to a battalion in Nyaunglebin District as a porter. He fled in February 2002. Photo #A91: M--- is a 27 year old Burman Buddhist from xxxx village in central Burma. He was working in a broker’s sales centre when he was arrested and put in M--- prison. He was then sent to porter with LIB #255 in Papun District. He later fled the unit and escaped when he could no longer endure the conditions. Photo #A92: M--- is a 45 year old Burman Buddhist farmer from xxxx township in central Burma. He was arrested in January 2002 when he was coming back from watching a video. He was then forced to carry for the Army. He ran away when he could no longer endure the conditions. [Photos: KHRG]

Photos #D61, D62: This is the body of Soe Lwin Oo, a 25 year old farmer from Kyaut P’Daung who was arrested, sent to prison and then taken as a convict porter by LIB #66 in northern Papun District. He fled the column and stayed in the jungle for 10 days. Villagers gave him some food and KNLA soldiers went to see him to invite him to come to their camp. He could no longer walk so the soldiers left him there. The next day, February 11th 2002, the soldiers went back to see him but he was already dead. These photos were taken at Kwee Doh Hta on February 13th 2002. Photo #A93: M---, a married Burman car driver from xxxx, Pegu Division, was arrested by military policemen who placed an illegal lottery ticket in his pocket. He was sent to prison and then on to LIB #255. While portering for the battalion the soldiers punched him in the nose and his nose bled. He ran away because he could not endure it anymore. Photo #A94: A---, 29 years old Burman, was a pedal trishaw driver in xxxx, Pegu Division. He was put in Pyi Prison for one year and six months for selling illegal lottery tickets. He wasthen sent to LIB #236 as a convict porter. He could not endure it anymore and fled. [Photos: KHRG]

Photo #A95: N--- is a 19 year old Burman farmer from xxxx town in central Burma. He was arrested for involvement in the illegal lottery and sent to Kathan Prison. He was then sent to LIB #251 in Papun District where he had to porter. He could not endure it anymore and fled in early 2002. Photo #A96: Convict porters Ko T---, Ko K--- and Ko A--- who escaped from the SPDC column they were portering for in Papun District in 2002. All three men were convicted for drug use and sent to Done Yit #1, an SPDC convict labour camp producing stone. When SPDC Army units needed porters, they were among prisoners taken to the frontline. Photo #A97: When convict porter K--- was no longer able to carry his load, SPDC soldiers tried to kill him by slashing his neck with a knife. He protected himself by putting up his hands which were slashed instead. The scars can be seen on his wrists in this photo. He then rolled himself down a mountainside and was left behind by the soldiers. This photo was taken in Nyaunglebin District in February 2002. Photo #A98: M---, a 47 year old Rakhine Buddhist farmer from xxxx township, Rakhine State, fled from the column he was forced to porter with on June 20th 2002. A soldier from LID #66 beat him with a stick two or three times a day when he could not carry anymore. When he could no longer endure it , M--- fled and was later found by the KNU. Photo #A99: M--- is 17 years old. He escaped from the SPDC Army column he was forced to porter for in August 2002. He was originally arrested by SPDC authorities and forced to join the Army. He was sent to #9 Army Training Centre, but escaped the next day. He was arrested again, this time for desertion and sent to prison for one year. He was eventually sent to the frontline as a porter. He told KHRG researchers he was beaten while portering. [Photos: KHRG]