Tatmadaw forces continue to deliberately target civilians, civilian settlements and food supplies in northern Papun District. On February 25th 2011 shelling directed at communities in Saw Muh Bplaw, Ler Muh Bplaw and Plah Koh village tracts in Lu Thaw Township displaced residents of 14 villages as they sought temporary refuge at hiding sites in the forest. After villagers fled, Tatmadaw troops looted civilians' possessions, burned parts of settlement areas and destroyed buildings and food stores in Dteh Neh village. No civilian deaths or injuries were reported to result from this shelling; local village heads confirmed that all villagers affected managed to flee to safe locations during the shelling, many because of warnings received through a locally-developed system to alert community members of attacks. This report is informed by KHRG photo documentation, as well as interviews with and written testimony from a total of nine village heads, village tract leaders and village officials from communities located or hiding in the affected area. An additional 41 interviews conducted during February and March 2011 in Lu Thaw Township were also drawn upon.

In February 25th 2011, villagers from a total of 14 villages in Saw Muh Bplaw, Ler Muh Bplaw and Plah Koh village tracts in Lu Thaw Township, Papun District, temporarily fled shelling by a column of soldiers from Tatmadaw Light Infantry Battalion (LIB) #252, according to local sources that spoke with KHRG.[1] One source also reported that Tatmadaw soldiers fired small arms at civilian residences during the attacks, which KHRG confirmed with photographic evidence. Following sustained mortar fire, Tatmadaw troops entered Dteh Neh village in Saw Muh Bplaw village tract after residents had fled, and burned down at least one house and two rice barns, stole villagers' animals, destroyed agricultural equipment, poured out stores of paddy grain, and ransacked and dismantled five houses.

Tatmadaw LIB #252, under the control of Battalion Commander Thein Zaw, is currently based at a hilltop camp near Plah Koh village, on the Kyaukkyi to Saw Htah vehicle road, approximately two hours on foot from the location of the attacks. Soldiers from Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA) 5th Brigade are also active in the area. According to local sources, prior to the attack on February 25th, no clashes between the KNLA and Tatmadaw had recently occurred in the area. The attacked area hosts a number of communities that are in hiding and actively evading Tatmadaw forces in the hills east of the Pwa Ghaw – Kler Lah vehicle road, between Plah Koh, Saw Muh Bplaw and Ler Muh Bplaw village tracts.[2]

KHRG spoke with village leaders from Gklaw Bpaw Kee, Ta Baw Kaw Der, Dteh Neh, Ler Kleh, Plah Koh and Htee Moo Kee villages, as well as with the Saw Muh Bplaw village tract leader; all of these sources were present in the affected area during the attacks, and confirmed that residents fled from these villages as soon as mortar fire began. Saw H---, 37, the Saw Muh Bplaw village tract leader, additionally confirmed that villagers fled from Bplar Law Dteh, Dteh Boh Bplaw, Htee Baw Kee, Khaw Lah Htah, Dteh Boh Htar, Kyaw Ghaw Loo and Htaw Htee Kee villages in his village tract, as soon as shells began falling in the area.

"Suddenly, the SPDC Army [Tatmadaw soldiers] came and attacked. We heard a lot of shelling. Immediately, we parents had to find our families and fled during the shelling… When we fled, we couldn't carry any food or anything. We just had to flee like that [empty-handed]. It's fine if we are safe."

- Saw K--- (male, 26), Plah Koh village, Lu Thaw Township (March 2nd 2011)

The following table provides an overview of locations in which shelling and displacement were reported to KHRG, as well as details on the source of information about each location:

|

Village

|

Village Tract

|

Incident

|

Reported by

|

|

|

1

|

Plah Koh

|

Plah Koh

|

Shelling audible; villagers fled

|

Saw K---, 26, Plah Koh village head; Saw H---, 37, Saw Muh Bplaw village tract leader[3]

|

|

2

|

Ler Kleh

|

Plah Koh

|

Field huts shelled; villagers fled

|

Saw N---, 40, Ler Kleh village head

|

|

3

|

Hsaw Gker Der

|

Plah Koh

|

Tatmadaw soldiers camped nearby on February 24th; village shelled; villagers fled

|

Saw W---, 54, Htee Moo Kee village head; Saw R---, 51, Ta Baw Kaw Der village official;[4] Saw H---, 37, Saw Muh Bplaw village tract leader

|

|

4

|

Htee Moo Kee

|

Ler Muh Bplaw

|

Village shelled; villagers fled

|

Saw H---, 37, Saw Muh Bplaw village tract leader; Saw L---, 30, Dteh Neh village head

|

|

5

|

Gklaw Bpaw Kee

|

Saw Muh Bplaw

|

Shelling audible; villagers fled

|

Saw T---, 40, Gklaw Bpaw Kee village head

|

|

6

|

Bplar Law Dteh

|

Saw Muh Bplaw

|

Village shelled; villagers fled

|

Saw L---, 30, Dteh Neh village head; Saw H---, 37, Saw Muh Bplaw village tract leader

|

|

7

|

Dteh Neh

|

Saw Muh Bplaw

|

Village shelled; villagers fled; one house and two rice barns burned; animals stolen; food stores and field equipment destroyed

|

Saw L---, 30, Dteh Neh village head; Saw N---, 40, Ler Kleh village head; Saw R---, 51, Ta Baw Kaw Der village official; Saw H---, 37, Saw Muh Bplaw village tract leader

|

|

8

|

Ta Baw Kaw Der

|

Saw Muh Bplaw

|

Village shelled; villagers fled

|

Saw P---, 24, Ta Baw Kaw Der village head

|

|

9

|

Dteh Boh Bplaw

|

Saw Muh Bplaw

|

Village shelled; villagers fled

|

Saw T---, 40, Gklaw Bpaw Kee village head; Saw H---, 37, Saw Muh Bplaw village tract leader; Saw W---, 54, Htee Moo Kee village head

|

|

10

|

Htee Baw Kee

|

Saw Muh Bplaw

|

Village shelled; villagers fled

|

Saw L---, 30, Dteh Neh village head

|

|

11

|

Khaw Lah Htah

|

Saw Muh Bplaw

|

Village shelled; villagers fled

|

Saw H---, 37, Saw Muh Bplaw village tract leader

|

|

12

|

Dteh Boh Htar

|

Saw Muh Bplaw

|

Village shelled; villagers fled

|

Saw H---, 37, Saw Muh Bplaw village tract leader

|

|

13

|

Kyaw Ghaw Loo

|

Saw Muh Bplaw

|

Village shelled; villagers fled

|

Saw H---, 37, Saw Muh Bplaw village tract leader

|

|

14

|

Htaw Htee Kee

|

Saw Muh Bplaw

|

Shelling audible; villagers fled

|

Saw H---, 37, Saw Muh Bplaw village tract leader

|

According to the sources detailed in the table above, soldiers from Tatmadaw LIB #252 left a hilltop camp in Plah Koh on February 24th and camped in the Saw Gker Der area of Plah Koh village tract. The next morning, on February 25th at approximately 7:30 am, troops began to fire mortars into civilian areas and agricultural workplaces in the vicinity of Ler Kleh in Plah Koh village tract, Htee Moo Kee in Ler Mu Bplaw village tract and Dteh Bpoh Bplaw, Dteh Neh and Ta Baw Kaw Der in Saw Muh Bplaw village tract. Mortar fire continued for approximately one hour, during which time the head of Htee Moo Kee village, Saw W---, 54, estimated that more than 100 mortars were fired. According to the KHRG field researcher who documented this incident, the attack specifically targeted agricultural workplaces, field huts[5] and field equipment; items destroyed by mortar fire include a tractor valued at 22,000 Thai baht (approximately US $725) belonging to Saw R---, 51, a resident of Ta Baw Kaw Der village.

"The SPDC Army [Tatmadaw soldiers from] LIB #252, led by Battalion Commander Thein Zaw and based in Plah Koh army camp, on the hill, left from their camp on February 24th 2011 and slept one night during their trip beside Hsaw Gker Der village. At around 7:30 am on February 25th 2011, they came and fired [mortars] at Hsaw Gker Der villagers' field huts. The villagers had to flee during the shelling suddenly, because they didn't get the news [warning] in advance. The SPDC Army shelled a lot of mortars, and until now the villagers have had to stay in fear and don't dare to go and do their livelihoods."

- Saw R--- (male, 51), Ta Baw Kaw Der village, Lu Thaw Township (March 2nd 2011)

According to reports from the local village heads that spoke with KHRG, no villagers were injured or killed during the shelling and all managed to flee their villages and take refuge at temporary hiding sites in the forest. While many villagers had to flee without warning, three villagers interviewed by KHRG following the attacks on February 25th described how people in their communities, or they themselves, moved to safety because of warnings received from other villagers. The village head of Gklaw Bpaw Kee, a village in Saw Muh Bplaw village tract from which residents fled during the shelling, described how other community members came to warn him of the attack while he was in his hill field outside the village. He explained that, even though the villagers were unable to find him at that time, they fired three warning shots from a gun to communicate that Tatmadaw troops were firing mortars near the village.[6]

"The SPDC Army [Tatmadaw soldiers] based in Plah Koh army camp came to operate and fired [mortars] at the Dteh Neh area. They saw some of the villagers' huts and fired at them many times. I didn't know any news about this, as it happened [the morning after] I had gone to my hill field for the night. So, my villagers worried about me very much and went to find me. They didn't reach me, but they went near my hill field and warned me by firing a gun three times. Therefore, I knew that the SPDC Army had come to fire at the villagers in the village. Then, I fled back immediately to my village and didn't see any villagers. I was very afraid and went to find my villagers, and then I saw them in the forest."

- Saw T--- (male, 40), Village head, Gklaw Bpaw Kee village, Lu Thaw Township (March 2nd 2011)

Many communities use self-protection strategies like those described by villagers interviewed by KHRG after the attacks on February 25th. Strategies used by villagers and documented by KHRG include: sharing information via radio communications; monitoring troop movements and maintaining general states of alertness to signals of attack; posting lookouts; and establishing agreed-upon signals to warn communities of impending attacks. Prior to the attacks on February 25th, for example, residents of at least Saw Muh Bplaw village tract had noted evidence of Tatmadaw movements, and returned to warn their community. In other locations, as described by Saw T--- above, residents fired an agreed-upon warning of three musket shots to warn residents beyond shouting distance.

"When it came into the morning we went to cut trees [to prepare our paddy field]. We had cut down only three trees and then… we heard from far away… people shot to let us know, so we came back to our house… They shot to let us know the situation wasn't good… They shot three times so we'd understand."

- Saw T--- (male, 40), Village head, Gklaw Bpaw Kee village, Lu Thaw Township (March 2nd 2011)

It is important to note that alarms and early warning systems also often entail civilians cultivating relationships with non-state armed groups that are in a position to share military intelligence useful for communities seeking to avoid attack.[7] In the case of attacks on February 25th, however, villagers appear to have used strategies that were wholly local and independent, without receiving warning from any external source.

"I didn't hear about it from the Karen National Union [KNU]. The villagers came back and informed us [that the Tatmadaw was active nearby] when they saw the path that the SPDC Army [Tatmadaw soldiers] had used during their patrol."

- Saw L---, 30, Village head, Dteh Neh village, Saw Muh Bplaw village tract, Lu Thaw Township (March 1st 2011)

In the case of attacks on February 25th, alarms and early warning systems were employed to prevent death and injury to civilians, who are deliberately targeted by Tatmadaw troops in upland areas. Not all communities received warnings, however; residents of Hsaw Gker Der, for example, told KHRG of having to flee suddenly and without warning. In a separate incident, a few days earlier on February 18th 2011, Saw B---, 45, was shot and killed by Tatmadaw troops, near Si Day village in Kay Bpoo village tract, farther north along the Pwa Ghaw to Kler Lah road. Saw B--- was carrying a rifle or musket for hunting small game at the time; Saw M---, the Kay Bpoo village tract leader, reported that Tatmadaw soldiers took the gun from him, along with his watch, food and some money, after he was shot. According to another villager interviewed by KHRG, Saw B--- was a member of his village's 'gher der' home guard,[8] and was gathering information about Tatmadaw troop movements along the section of the Pwa Ghaw to Kler Lah vehicle road that passes near his village at the time he was killed. KHRG has yet to confirm further details of this incident, including whether Saw M--- was directly participating in hostilities at the time he was killed. Three other residents of Kay Bpoo village tract interviewed by KHRG in 2011 mentioned that Tatmadaw forces have been active in Kay Bpoo village tract along the Pwa Ghaw to Kler Lah road since January 2011, as rations have been transported rations using both trucks and convict porters.

"Villagers haven't got injured [in Kay Bpoo] but they shot one villager yesterday [recently]. The villager's name is Saw B---. He's a Si Day villager. He's 45 years old. He's single. … They [the soldiers who shot Saw B---] took several things. As we know, they took a watch, some money, a gun for shooting animals and snacks."

- Saw M---, 40, Kay Bpoo village tract leader, Lu Thaw Township, Papun District (March 9th 2011)

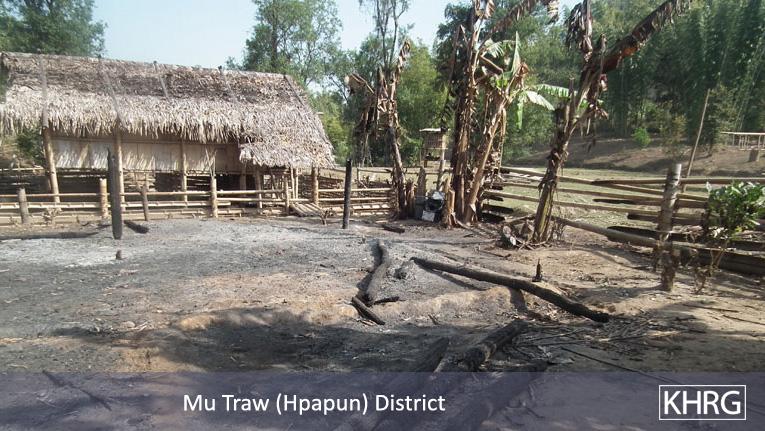

While villagers were able to effectively avoid injury during the attack on February 25th, the head of Dteh Neh village reported that troops from LIB #252 subsequently entered, looted and destroyed civilians' houses and possessions in Dteh Neh village; five other local village heads in Saw Muh Bplaw village tract offered reports that confirmed the details or location of this incident. The Dteh Neh village head reported that one house was burned down, two rice barns were destroyed and villagers' animals were taken and eaten by Tatmadaw soldiers. Other sources reported that the soldiers had destroyed five other houses and agricultural equipment after entering Dteh Neh. According to the KHRG field researcher who conducted interviews and photo documentation in Dteh Neh village, paddy grains were also poured out of a rice store which contained 120 tins of paddy (1254 kg. / 2765 lb.), and Tatmadaw soldiers made holes in or otherwise purposefully damaged food and water storage containers and kitchen implements. Photographs taken the next day by a KHRG researcher depict systematic repetition of the same types of acts: walls kicked in and centre-posts pulled down, house-by-house; animal enclosures and gardens shot at or hacked with machetes; food supplies thrown on the ground and trod over with boots; cooking implements burned or beaten out of shape.

"As these villagers are displaced villagers, they had to flee in fear suddenly during the shelling. Then, the SPDC Army [Tatmadaw soldiers] came to burn down a villager's hut and destroyed two rice barns. They also took villagers' animals to eat and went back to their army camp immediately. … They shelled over 30 mortars. … They ate seven ducks of M--- and one goat belonging to D---'s mother. … They burned Ht---'s mother's paddy. … They burned 90 big tins of paddy (941 kg. / 2074 lb.). … They also burned paddy kept in a rice barn. They burned one rice barn owned by N---'s mother. … It was more than 10 or around 20 big tins of paddy (105 – 209 kg. / 230 – 461 lb.). … They took all the rice owned by K--- and also took a lot of other property. They [the damaged property] will cost over 50,000 [baht]. … They destroyed all the buildings to keep the ducks or other animals [pens] by firing bullets. They also broke all pots, pans, plates, and so on."

- Saw L---, 30, Village head, Dteh Neh village, Saw Muh Bplaw village tract, Lu Thaw Township, Papun District (March 1st 2011)

"They patrolled around villages inside the Dteh Boh Bplaw area. At first they didn't enter any villages, but then when they entered [a village] they burned one house, along with everything in the house, including one rice mill. They also destroyed villagers' houses, poured out stored paddy grains and destroyed mattocks. Everything they saw, they destroyed it all. The place [where they burned a house] is called Dteh Neh. … In that house, there were lots of things. The house owner sold many things in that house [shop] so many kinds of things were burned with the house. Under the house, one rice mill was burned and they also shot many times at the rice mill. … The person who had his house burned is Saw Pe---. … The owner [Saw P---] notified us that the total value was 58,000 baht (approximately US $1,910). … They destroyed a total of four houses, including one house [that was] burned. For the other three, they destroyed those too, and also one chicken pen. … Before they entered the villages, they shot many times and didn't kill or catch villagers, because the villagers were also aware of it. Villagers and children all fled to safety."

- Saw H---, 37, Village head, Hsaw Paw Der village, Plah Koh village tract, Luthaw Township, Papun District (March 1st 2011)

"At 7:30 in the morning, the SPDC [Tatmadaw soldiers] suddenly came and fired [mortars] at villagers in their field huts. We heard a lot of shelling and we had to flee suddenly. The SPDC Army [Tatmadaw soldiers] shelled a lot of mortars. We were very afraid that the mortars would hit us. We couldn't bring anything when we fled. We just fled. This SPDC unit [Tatmadaw LIB #252] entered one villager's house and destroyed two rice barns, and went back."

- Saw N---, 40, Village head, Ler Kleh village, Plah Koh village tract, Luthaw Township, Papun District (March 2nd

2011)

The incidents on February 25th demonstrate that patterns of Tatmadaw practices previously documented by KHRG continue today as in the past; villages are shelled remotely, after which troop columns sometimes enter the recently abandoned villages to loot and destroy villagers' houses and possessions.[9] In particular, these recent events conform to a pattern of attacks which KHRG has documented in upland areas of Papun District, as well as in adjacent areas of Nyaunglebin and Toungoo Districts, since the termination of the 2005-2008 Offensive in northern Karen State. While no coordinated multi-battalion offensive on the area appears to have yet resumed, periodic attacks targeting civilians continue.[10] The use of temporary strategic displacement by villagers in the face of such physical security threats also continues to be widely utilised by communities in this area, as documented by KHRG, during both sustained multi-battalion offensives and during seasonal shelling and patrol operations.

This photo, taken on February 26th 2011, shows an area of Dteh Neh village still on fire the day after an attack by Tatmadaw LIB 252. Villagers fled mortar fire and, in their absence, Tatmadaw soldiers looted and destroyed civilian structures and possessions. [Photo: KHRG]

These photos, taken on February 26th 2011, show a crater from a mortar shell (above left) and used bullet cartridges (above right) lying on the ground around Dteh Neh village the day after the attack by Tatmadaw LIB #252; bullet holes and other evidence of small arms fire are also visible in support poles of houses (below left) and animal enclosures (below right). Local village heads reported that Tatmadaw soldiers deliberately fired small arms, as well as mortars, at and within civilian settlements. The head of Dteh Neh village, Saw L---, 30, reported that around 30 mortars were fired in the vicinity of Dteh Neh village, while the Htee Moo Kee village head, Saw W---, 54, estimated that a total of more than 100 mortars were fired. These conflicting accounts may be due to the different geographical locations of the villages. [Photos: KHRG]

KHRG spoke with village leaders from Gklaw Bpaw Kee, Ta Baw Kaw Der, Dteh Neh, Ler Kleh, Plah Koh and Htee Moo Kee villages, as well as with the Saw Muh Bplaw village tract leader; all of these sources were present in the affected area during the attacks, and confirmed that residents fled from these villages as soon as mortar fire began. Saw H---, 37, the Saw Muh Bplaw village tract leader, additionally confirmed that villagers fled from Bplar Law Dteh, Dteh Boh Bplaw, Htee Baw Kee, Khaw Lah Htah, Dteh Boh Htar, Kyaw Ghaw Loo and Htaw Htee Kee villages in his village tract, as soon as shells began falling in the area.

These photos, taken on February 26th 2011, show agricultural equipment damaged by Tatmadaw LIB 252. The photo above left shows a rice mill used to process raw paddy grain, belonging to Saw E--- in Dteh Neh village. According to Saw H---, the Saw Muh Bplaw village tract leader, Tatmadaw soldiers shot at the rice mill to destroy it; the photo above right shows a visible hole in the casing around the mill’s engine. The photo below right shows bullet holes in the engine of the rice mill belonging to Saw E---. In remote areas such as northern Lu Thaw, agricultural equipment has a value beyond market price; it will be exceedingly difficult for Saw E--- to replace the damaged property. The loss of essential agricultural equipment such as a rice mill, which is often relied upon by an entire village, can have an impact that reverberates throughout the community. [Photos: KHRG]

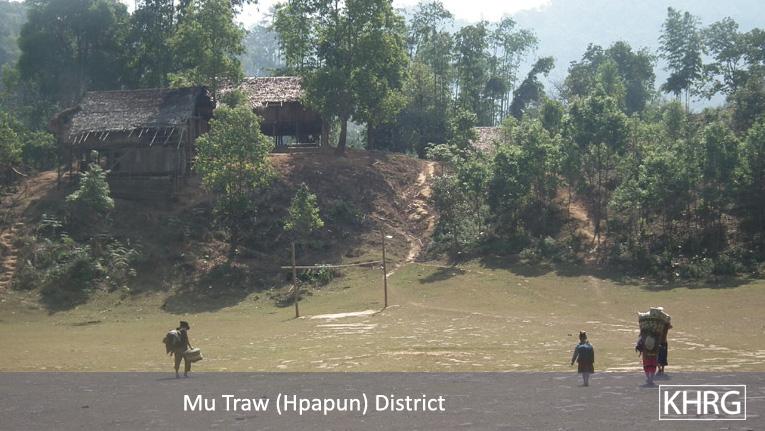

These photos, all taken on February 26th 2011, show villagers who fled shelling in the vicinity of Saw Hsaw Gker Der, Bplar Law Dteh, Plah Koh and Ta Baw Kaw Der villages on February 25th returning from a temporary refuge site to their homes. [Photos: KHRG]

In the photo on the left, taken on February 26th 2011 in Dteh Neh village, a large basket of milled rice has been punctured and overturned. The photo on the right, taken on the same day, shows paddy on the ground at another location in Dteh Neh where Tatmadaw also destroyed food stores. A large basket is a literal unit of weight measurement in eastern Burma; one large basket of unprocessed paddy weighs approximately 21 kg. (45 lb).; a basket of milled rice weighs 32 kg (70 lb.). A basket can be divided into two smaller units called big tins. A big tin of paddy weighs approximately 10.5 kg (23 lb.); a big tin of milled rice weighs 16 kg. (35 lb.). The KHRG researcher who documented the incidents described in this bulletin reported that at least one rice barn containing 120 big tins of paddy (1254 kg. / 2765 lb.) was poured out and destroyed in Dteh Neh village during the February 25th attack. Saw L---, the Dteh Neh village head, reported that two rice barns in Dteh Neh were burned, one of which contained 90 big tins of paddy (941 kg. / 2074 lb.) and one of which contained between 10 and 20 big tins of paddy (105 – 209 kg. / 230 – 461 lb.). [Photos: KHRG]

The photo on the right, taken on February 26th 2011, shows cooking pots damaged by Tatmadaw soldiers as well as paddy grains poured out by soldiers. The photo on the left, also taken on February 26th, shows empty containers used to store paddy grain and other comestibles. Villagers often use these containers to store hidden food caches in the forest in case of Tatmadaw attacks, as they protect food stores from animals and insects. In this photo, containers stacked near the rice mill pictured above have been smashed by Tatmadaw soldiers [Photos: KHRG]

The photo on the left, taken on February 26th 2011, shows an animal enclosure broken apart by soldiers from Tatmadaw LIB #252. Saw L---, the Dteh Neh village head, reported that animals were stolen and eaten during the previous day's attack on his village, and that animal enclosures were shot at and destroyed. Gardens were also deliberately damaged; the photo on the right, also taken on February 26th, shows banana trees in Dteh Neh chopped down by Tatmadaw soldiers. [Photos: KHRG]

These photos, all taken on February 26th 2011, show three distinct sites in Dteh Neh village burned by Tatmadaw troops on February 25th. Saw L---, the Dteh Neh village head, and the KHRG researcher who documented this incident both reported that one house and two rice barns were burned down in the attack. [Photos: KHRG]

The four photos above, all taken on February 26th 2011, show four distinct houses that were partially dismantled by Tatmadaw troops during the attack on Dteh Neh village the previous day; some of the walls have been torn off and bamboo poles used as roofing struts and floorboards have been pulled down and/or broken. In the photo on the bottom right, villagers’ possessions have been scattered and broken. Local village heads reported that soldiers from Tatmadaw LIB #252 systematically targeted villagers’ livelihoods in acts that went beyond looting, including the destruction of houses, field huts, agricultural and cooking equipment, food stores, animal enclosures and gardens. [Photos: KHRG]

Footnotes:

[1] This incident has also been recently documented by relief organisations and media groups. See: "Burma Army Shells and Burns Village in Northern Karen State," Free Burma Rangers, March 2011; "Heavy fire, landmines rock eastern Burma," Democratic Voice of Burma, March 2011. Free Burma Rangers reported that two buildings were burned; KHRG has since received additional information from the Dteh Neh village head and from the Saw Muh Bplaw village tract leader, who both reported that two rice barns and one house were burned. Note also that inconsistencies in name and place spellings in reports may be due to the use of different Karen to English transliteration keys during translation.

[2] For more information on this and other roads in Lu Thaw Township, and how they impact civilians' efforts to evade Tatmadaw attacks and survive with dignity in upland areas, see Self-protection under strain: Targeting of civilians and local responses in northern Karen State, KHRG, August 2010.

[3] Saw H--- lives in, and is the village head of Hsaw Paw Der village in Plah Koh village tract; he is also the Saw Muh Bplaw village tract leader.

[4] Saw R---, 51, is the Secretary of the Lu Thaw Township Organisational Department, as well as a resident of Ta Baw Kaw Der village who fled mortar fire in his village on February 25th 2011.

[5] Many villagers who keep farms or plantations in rural eastern Burma also build field huts to be able to stay near their agricultural projects during important points in the agricultural cycle, to protect crops from wild animals, and to reduce time spent travelling between their homes and their farms.

[6] For further discussion of self-protection strategies involving uses of weapons employed by villagers in Papun District, see: Self-protection under strain, KHRG, August 2010, pp. 82 – 100.

[7] The Local to Global Protection Project (L2GP Project) has critiqued one such system involving communications training and distribution of radio equipment by the Karen National Union (KNU) and other Karen organisations, the 'Care for Communities at Risk' programme, as allowing the KNU to more "fully penetrate civilian populations in the conflict zone, and thus control population movement." While based upon important concerns about the impact of non-state armed groups on civilians' freedom of movement, this critique requires conceiving of villagers in upland areas as a passive, homogenous population that can be 'penetrated' by an equally homogenous outside force. This denies the agency of individual villagers who make their own decisions about whether to participate in such a program, and obscures the dynamic nature of relationships between members of non-state armed groups and civilians who may have their own protection motivations for maintaining relationships with such groups, or individual group members. For the L2GP Project's full report, see Ashley South, Conflict and Survival: Self-protection in south-east Burma, Chatham House Asia Programme Paper 2010. Importantly, the L2GP's critique also appears to over-estimate the KNU's capacity to control population movements through communications or persuasion. During the 2005-2008 Tatmadaw offensive in the area, for example, the Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA) told village leaders in some parts of northern Lu Thaw that they would not be able to protect them and suggested they abandon the area. Underscoring the limits of KNLA control, many communities refused. For further discussion of these events, see Kevin Malseed, "Networks of Noncompliance: Grassroots Resistance and Sovereignty in Militarised Burma," KHRG Working Paper, April 2009; later published in: Journal of Peasant Studies 36:2, April 2009. A more pressing threat to freedom of movement for civilians in Lu Thaw are landmines placed by both the KNLA and Tatmadaw, particularly along roads, as well as Tatmadaw camps that make road usage or crossing unsafe. For discussion of these limitations to freedom of movement, see Self-Protection under strain, KHRG, August 2010.

[8] For more on 'gher der' home guard groups and direct participation in conflict by civilians, see Self-Protection under strain, KHRG, August 2010.

[9] For more on the deliberate targeting of civilians and civilian settlements by Tatmadaw patrols, see: Self-protection under strain, KHRG, August 2010, pp. 32-33; Village Agency: Rural rights and resistance in a militarised Karen State, KHRG, November 2008, pp. 120-125.

[10] Offensives are characterised by multi-battalion search and destroy operations against villages. Since 2008, KHRG has reported incidents of remote shelling or limited-range patrols in areas proximate to camps, in which soldiers will deliberately target and shoot villagers, and burn houses, food stores, field huts and/or fields, but not necessarily as part of a geographically broader, coordinated operation. This conforms to established Tatmadaw practices in shoot-on-sight areas, but not to the widespread, sustained operations associated with an offensive. For more on the targeting of civilians in Papun District, see "Attacks, killing and the food crisis in Papun", KHRG, February 2009; Self-protection under strain, KHRG, August 2010, pp. 32-33. For further details on the direct consequences of these attacks on villagers' livelihoods and food security, see "Starving them out: Food shortages and exploitative abuse in Papun District," KHRG, October 2009.