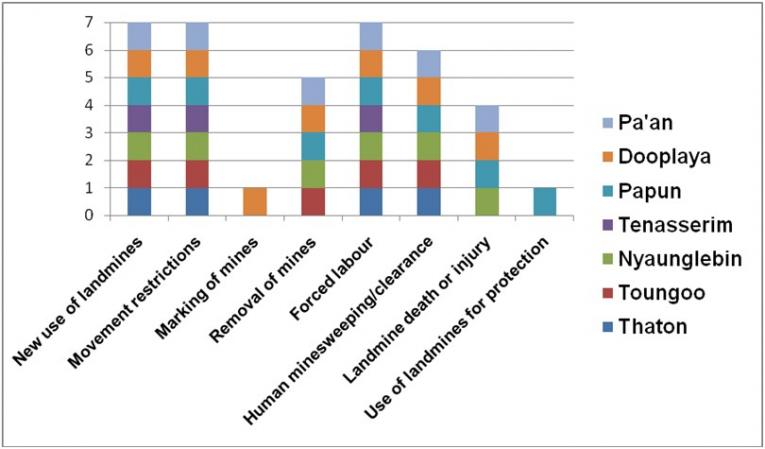

Analysis of KHRG's field information gathered between January 2011 and May 2012 in seven geographic research areas indicates that, during that period, new landmines were deployed by government and non-state armed groups (NSAGs) in all seven research areas. Ongoing mine contamination in eastern Burma continues to put civilians' lives and livelihoods at risk and undermines their efforts to protect against other forms of abuse. There is an urgent need for humanitarian mine action that accords primacy to local protection priorities and builds on the strategies villagers themselves already employ in response to the threat of landmines. In the cases where civilians view landmines as a potential source of protection, there is an equally urgent need for viable alternatives that expand self-protection options beyond reliance on the use of mines. Key findings in this report were drawn based upon analysis of seven themes, including: New use of landmines; Movement restrictions resulting from landmines; Marking and removal of landmines; Forced labour entailing increased landmine risks; Human mine sweeping, forced mine clearance and human shields; Landmine-related death or injury; and Use of landmines for self-protection.

I. Introduction and executive summary

|

"I have known about the farms that we don’t dare to go across. We don’t dare to go along the riverbank or cross the farms. Also we don’t dare to go to collect vegetables in the forest, because people planted ta su htee hkaw htee [in Karen literally: ‘hit hands hit legs’, meaning landmines]. We still don’t dare to go, we only stay in our garden. We just cut the mango tree branches. … We just want this problem to be solved in peace. … I mean taking out those landmines for us so we can work on our farms. We want to request that." Kw---, (female, 33), village head, Thaw Waw Plaw village,Noh Kay village tract, T’Nay Hsah Township, Pa’an District (Interviewed April 2012)[1] |

|

"In the past, soldiers planted landmines when they stayed here but people weren’t hit by them. I thought people travelled back and forth every day along this path, I went along it and I was hit by the landmine on the way home. … I was seven months pregnant. I didn’t know the reason why those people [my nephew and aunt] cried a lot because I thought the landmine blew up very far away. I was wrong because actually it hit my leg when I looked at my leg." Ma Nu---, (female, 33) Noh Kyaw village, Noh Kay village tract, T’Nay Hsah Township, Pa’an District (Interviewed April 2012)[2] |

Eastern Burma is one of the most landmine contaminated places in the world,[3]putting civilians' lives and livelihoods at risk and undermining their effort to protect against other forms of abuse. Villagers frequently voice concerns or raise issues related to living with the threat of landmines, but they are not the passive victims of an indiscriminate weapon: villagers employ a range of strategies to avoid dangerous mined areas and otherwise address their concerns. The strategiesvillagers employ in response to the threat of landmines are also not always sufficient, however, and there is an urgent need for humanitarian mine action that accords primacy to local protection priorities and builds on the strategies villagers themselves already employ in response to the threat of landmines. At the same time, local perspectives on landmines are not uniform. Depending on the local dynamics of abuse and the actor employing landmines, civilians may also view landmines as a potential source of protection. In these cases, there is an equally urgent need for viable alternatives that expands self-protection options beyond reliance on the use of mines.

This report focuses on information gathered between January 2011 and May 2012, documenting the challenges and responses of communities in landmine contaminated areas across seven geographic research areas in eastern Burma. The enduring crisis of landmines means that concerns raised prior to the reporting period continue to devastate communities today, even in places where conflict has subsided. Villagers are seeking their own solutions, but they are also explicitly requesting outside support. On May 12th 2012, some 37 residents of a village in Noh Kay village tract, Pa’an District

[4] submitted their names and requested that KHRG make known the fact that landmines are preventing them from accessing a total of 13 flat paddy fields and 23 cash-crop plantations. These villagers requested that KHRG share publicly their names and village name in order to encourage urgent de-mining of this area.[5] Eight residents of a neighbouring village in the same village tract who were interviewed by KHRG also described being unable to access agricultural areas and explicitly requested mine removal.[6] On the very same day that this information was provided to KHRG, a community member in the area reported that two more landmines had just exploded, injuring two livestock animals. Since the beginning of 2012, this village tract and two others have recorded the detonation of at least 36 landmines, killing or injuring five villagers and 31 livestock animals.[7]

In order to encourage strong action to address villagers’ landmine concerns that is also cognisant of the complex local dynamics of abuse in eastern Burma, this report aims to inform stakeholders of the range of specific landmine concerns expressed by villagers, as well as the self-protection strategies they use to address these and other related human rights concerns. Strong mine action should build upon the strategies villagers living amongst landmines already employ. In cases where villagers believe that a mine presents less harm in their community than military or economic activities, focus should be on providing villagers with viable alternatives to protect themselves beyond the use of landmines. Humanitarian actors must also recognise the interrelated nature of abuse in eastern Burma, and address the fact that landmine removal may facilitate other forms of abuse, where it serves to enable the pursuit of military or economic activities undertaken to the detriment of rural ethnic communities.

For the purposes of this report, seven KHRG staff analysed English translations of a total of 603 oral testimonies and written pieces of human rights documentation received between January 2011 and May 2012,[8], as well as 141 sets of images. 119 of the documents raised concerns or dealt with issues related to the use of landmines in eastern Burma, 55 of which have also been published on the KHRG website in their entirety. Relevant excerpts from all 119 of these documents are included in Section III: Source Documents.

Key findings

-

Landmines were deployed by government and NSAGs in all seven KHRG research areas and ongoing mine contamination continues to place civilians’ lives and livelihoods at severe risk. No significant mine action has been undertaken and landmine removal by armed actors has been incomplete, unsystematic and not necessarily motivated by a desire to protect civilians.

-

Local perspectives on landmines are not uniform and, depending on the geographic area and the actor employing landmines, civilians viewed the use of landmines as a threat to their safety and/or potentially as a source of protection.

-

Humanitarian mine action must be undertaken as soon as possible and must include consultation that accords primacy to the priorities and concerns of communities living with the threat of landmines.

-

Villagers employ a variety of self-protection strategies designed to address the risks presented by landmines. While local responses alone are insufficient to protect villagers in many cases, humanitarian mine action will be most effective where it builds on these already existing strategies. Government, funding bodies and NGOs should continue to support actors that can consistently access populations at risk to help them better address their own landmine concerns.

-

Landmines present added risks to villagers facing other forms of abuse, including forced labour and displacement. This must be taken into account during any discussion of refugee repatriation. Military and civilian officials must immediately cease forced labour demands and take active steps to prosecute offenders who continue to issue them.

Executive summary

Based on an assessment of KHRG field information received during the reporting period, this report identifies trends of different types of landmine-related events and issues in seven geographic research areas in eastern Burma, which stretch across four of the country’s 14 states and regions: all or portions of Mon and Kayin states and Bago and Tanitharyi regions. Divided into seven parts, Section II: Analysis, below, presents KHRG’s documentation and analysis on each of the following themes:[9]

A. New use of landmines;

B. Movement restrictions resulting from landmine contamination;

C. Marking, fencing and removal of landmines;

D. Human mine sweeping, forced mine clearance and human shielding;

E. Forced labour entailing increased landmine risks;

F. Landmine casualties (death or injury);

G. Landmine use as a self-protection strategy.

Section II: A indicates that, throughout the reporting period, new landmines were deployed by both government and NSAGs in all seven KHRG research areas, while Section II: B illustrates concerns raised by affected communities about ongoing landmine contamination as a threat to their safety, a barrier to free movement and an obstacle to the pursuit of livelihood activities.

Section II: C raises villagers’ concerns that armed actors were unwilling or unable to remove mines. Where landmines were removed by government and NSAG forces, documented occurrences of this were ad hoc, sporadic and not necessarily motivated by a desire to protect civilians. In some cases, armed forces or groups were unable to systematically remove landmines, because they could not recall the locations of all mines planted or because multiple armed actors had mined a given area. In Noh Kay village tract in Pa’an District, for example, a cooperative effort by local Tatmadaw Border Guard and KNLA forces to remove landmines in was called off after one Border Guard soldier among the party was injured by a landmine.

Section II: D describes how, in three of the research areas, government forces responded to landmine threats by forcing civilians to sweep for, remove or otherwise shield them from landmines. Section II: E outlines the ways in which civilians facing other forms of abuse, such as demands for forced labour in service as porters, guides or messengers were also subject to an increased risk of death or injury from landmines, where compliance required them to work in close proximity to troops or travel in unfamiliar areas. As of May 2012, forced labour orders from military and civilian officials continued to be issued in at least four KHRG research areas[10] and no prosecution of offending officials has yet been reported.[11]

Section II: F outlines landmine casualties described in KHRG field documentation in four research areas. Treatment data provided by local community-based health organisations meanwhile confirmed additional new landmine casualties in all seven research areas during the reporting period. Displaced villagers, returning refugees or villagers travelling in unfamiliar areas while complying with forced labour demands were subject to increased risks of death or injury from landmines. These increased risks underscored the way that local knowledge of mine-affected areas continued to be a key tool for villagers seeking to protect themselves from harm, although even detailed knowledge or cooperation from the armed actor responsible for the landmines was not always sufficient.

Section II: G explains that, in one research area, villagers described landmines as a source of protection that impeded attacks by government troops and facilitated access to agricultural areas. The viewpoint of individual villagers was in all cases shaped by the specific local dynamics of abuse and the villager’s own opinions about the protective intent of the actor employing the landmines, whether government, NSAG or gher der home guards.

Throughout all seven sections, particular attention is paid to the strategies villagers adopted to respond to their landmine-related concerns. Strategies included: removing, deactivating or marking landmines; sharing information regarding areas known to be mined; pursuing alternate livelihoods activities outside of mined areas; using alternate travel routes or methods of travel; and requesting armed actors to remove old mines or refrain from planting new ones. Landmine victims and their families sought and received medical assistance, food and financial support from other villagers and from non-state actors, including local community-based health and humanitarian organisations.

Methodology

Field Research

KHRG has gathered testimony and documented individual incidents of human rights violations in eastern Burma since 1992. Research for this report was conducted by a research network of community members working with KHRG, some drawing salary and other material support, and some working as volunteers. KHRG trains local people from all walks of life and a variety of backgrounds to document the issues that affect their community. KHRG’s recruitment policy does not discriminate on the basis of ethnic, religious or personal background, political affiliation or occupation. We train anyone who has local knowledge, is motivated to improve the human rights situation in their own community and is known to and respected by members of their local communities. Recognising that in all cases, no one is truly ‘neutral’ and everyone has competing viewpoints and interests, KHRG seeks always to filter every report through those interests and to present evidence from as many sources and perspectives as possible.

Community members who submitted information contained in this report were trained and equipped to employ KHRG’s documentation methodology, including to:

• Gather oral testimony, by conducting audio-recorded interviews with villagers living in eastern Burma. When conducting interviews, local people working with KHRG are trained to use loose question guidelines, but also to encourage interviewees to speak freely about recent events, raise issues that they consider important and share their opinions or perspectives on abuse and other local dynamics.

• Document individual incidents of abuse using a standardised reporting format. When writing or gathering incident reports, local people working with KHRG are encouraged to document incidents of abuse that they consider important, by verifying information from multiple sources, assessing for potential biases and comparing incidents to local trends of abuse.

• Write general updates on the situation in areas with which they are familiar. When writing situation updates, local people working with KHRG are encouraged to summarise recent events, raise issues that they consider important, and present their opinions or perspectives on abuse and other local dynamics in their area.

• Gather photographs and video footage. Local people are trained by KHRG to take photographs or video footage of incidents as they happen when it is safe to do so or, because this is rarely possible, of victims, witnesses, evidence or the aftermath of incidents. Local people are also encouraged to take photographs or video footage of other things they consider important, including everyday life in rural areas, cultural activities and the long-term consequences of abuse.

• Collect other forms of evidence where available, such as letters written by military commanders ordering forced labour or forced relocation.

Verification

KHRG trains community members to follow a verification policy that includes gathering different types of information or reports from multiple sources, assessing the credibility of sources, and comparing the information with their own understanding of local trends. KHRG information-processing procedure additionally involves the assessment of each individual piece of information prior to translation in order to determine quality and facilitate follow-up with community members where necessary.

This report does not seek to quantify a total number of landmine-related incidents across research areas; where provided, figures indicate only those occurrences that were described in KHRG field documentation. KHRG reporting is designed primarily to share the perspectives of individuals and communities, rather than to focus on incident-based reporting or to quantify a number of confirmed incidents. Rather, emphasis is placed on locating concerns raised by communities, rather than seeking to disqualify testimony; because community members may not always articulate things clearly or keep exact records of landmine-related incidents. In many cases, villagers raised concerns about issues not tied to a specific time or place, or described events which were not discussed elsewhere in KHRG documentation. This report seeks to emphasise the cumulative weight of the large data set analysed for this report, and the consistency with which landmine-related concerns were raised by communities across a wide geographic area.

Every piece of information in this report is based directly upon testimony articulated by villagers during the reporting period or by documentation and analysis written by other community members living and working in the same area. In order to make this information transparent and verifiable, all examples have been footnoted to either 55 published KHRG reports or 64 previously unpublished source documents, which are also available in Section III of this report. Wherever possible, this report includes excerpts of testimony and documentation to illustrate examples highlighted by KHRG. In all cases, the testimony comes from people who have themselves directly experienced issues including movement restrictions and physical security threats arising from the use of landmines in eastern Burma.

Analysis for this report

This report focuses on field information received between January and December 2011. Key updates relating to the use of landmines in 2012 were also included, however due to the sheer volume of information that KHRG regularly receives, all field information received since the beginning of 2012 has not yet been closely analysed. For example, during 2011 alone, community members working with KHRG collected a total of 1,270 oral testimonies, sets of images and documentation written by villagers, including: 523 audio-recorded interviews, 220 incident reports, 84 situation updates, 125 other documents written by villagers, 111 sets of photos and video amounting to a total of 12,517 images, and 207 written orders issued by civilian and military officials. Interviewees included both village leaders and persons not in positions of leadership, as well as men, women and youths. KHRG is committed to interviewing villagers from all ethnic groups within its research areas. The majority of villagers interviewed belong to different sub-ethnicities of Karen, however interviews were also conducted with other ethnic groups, including Burman, Pa’O, Mon, Chin, Karenni, Arakan and Shan villagers.

In order to systematically analyse data and draw conclusions regarding the use of landmines in eastern Burma, seven KHRG staff analysed English translations of a total of 603 oral testimonies and pieces of written human rights documentation received between January 2011 and May 2012, as well as 141 sets of images.[12] Of these, 119 described events, raised concerns or dealt with issues related to the use of landmines in eastern Burma. Relevant excerpts from all 119 of these documents are included in Section III: Source Documents below, namely 70 interviews and 49 other written reports received by KHRG since January 2011 and prior to the middle of May 2012, of which 55 have also been published on the KHRG website in their entirety.

KHRG analysed these documents for seven themes: The new use of landmines by government forces and non-state armed groups (NSAGs); Movement restrictions resulting from landmines; Marking and removal of mines; Human mine sweeping, forced mine clearance and human shields; Forced labour entailing increased landmine risks; Landmine-related death and injury, and; Use of landmines for self-protection. Special attention was given to note local strategies for addressing concerns related to all of these themes. The results of this analysis are summarised in Table A.1 below, while more detailed analysis of each theme makes up the bulk of this report in Section II.

Landmines are uniquely difficult to research, particularly when it comes to attributing the use of landmines to specific actors, for two reasons. First, unless an individual witnesses a specific actor place a landmine, it can be difficult to conclusively determine which actor is responsible for a given landmine. Nonetheless, local people are often able to identify with credible accuracy what actor is responsible for a given landmine based upon other factors, including their own often detailed knowledge of the activities and territory of specific armed actors, as well as statements made or information provided by such actors. Second, an individual’s own perspective on the legitimacy of landmine use by a given actor is likely to be impacted by whether they view that actor as generally a threat or a protector of their well-being. This, as well as personal security concerns, may also impact an individual’s willingness to speak about landmines or attribute their use to a specific actor. In response to obstacles such as this, community members working with KHRG are taught to, wherever possible, determine why villagers believe a certain armed actor was responsible and to seek out multiple sources of information. In this report, KHRG attributes the use of landmines to a specific actor only where there is a credible basis for identifying this perpetrator.

Research areas

In order to classify information geographically, KHRG organised landmine-related information according to seven research areas: Thaton, Toungoo, Nyaunglebin, Tenasserim, Papun, Dooplaya and Pa’an. These seven research areas are commonly referred to as “districts” and are used by the Karen National Union (KNU), as well as many local Karen organisations, both those affiliated and unaffiliated with the KNU. KHRG’s use of the district designations to reference our research areas represents no political affiliation; rather, it is rooted in KHRG’s historical practice, due to the fact that villagers interviewed by KHRG, as well as local organisations with whom KHRG seeks to cooperate commonly use these designations. The seven districts do not correspond to any demarcations used by Burma’s central government, but cover all or parts of two government-delineated states and two regions. Toungoo District includes all of northwestern Kayin State and a small portion of eastern Bago Region, while Nyaunglebin District covers a significant portion of eastern Bago Region. Papun, Pa’an and Dooplaya districts correspond to all of northern, central and southern Kayin State, respectively. Thaton District corresponds to northern Mon State, and Tennasserim corresponds to Tanintharyi Region. In order to make information in this report intelligible to stakeholders more familiar with government designations for these areas, the maps in Figure 1 and Figure 2 include both the government demarcation system of states and regions, and the seven research areas, or “districts,” used when referencing information in this report. When transcribing Karen village names, KHRG utilizes a Karen language transliteration system that was developed in January 2012 in cooperation with fourteen other local Karen community-based organisations and NGOs to ensure the consistent spelling of place names.[13]

Censoring of names, locations and other details

Where quotes or references include identifying information that KHRG has reason to believe could put villagers in danger, particularly the names of individuals or villages, this information has been censored, and the original name has been replaced by a random letter or pair of letters. The censored code names do not correspond to the actual names in the relevant language or to coding used by KHRG in previous reports, with the exception of excerpts taken from previously published KHRG reports. All names and locations censored according to this system correspond to actual names and locations on file with KHRG. Thus, censoring should not be interpreted as the absence of information. In many cases, further details have been withheld for the security of villagers and KHRG researchers. Note also that names given by villagers have been transliterated directly, and may include relational epithets, such as mother, father, as well as terms that imply familiarity but are not necessarily indicative of a familial relationship, such as uncle or aunt.

Independence, obstacles to research and selection bias

Though KHRG often operates in or through areas controlled by armed forces and groups including the Tatmadaw, Tatmadaw Border Guard battalions and NSAGs, KHRG is independent and unaffiliated. Access to certain contexts has sometimes been facilitated by the Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA), particularly in cases where documentation activities required crossing vehicle roads or entering villages that the Tatmadaw had burned or were likely to be mined. Other groups were not willing to facilitate research by KHRG; Tatmadaw, Tatmadaw Border Guard and Democratic Karen Buddhist Army (DKBA) forces were the chief obstacles to safely conducting research in eastern Burma during the reporting period. Local people documenting human rights abuses did so with the understanding that they risked potential arrest or execution should perpetrators of abuse learn of their activities.

Because of the obstacles described above, it has only previously been possible for local people collecting testimony to interview civilians who are not likely to report documentation activities to authorities in a way that would place those people in danger. This does not represent a research constraint in areas where whole communities are in hiding, view authorities perpetrating abuse as a threat, and as such are likely to flee rather than risk encountering them. In other areas, however, security considerations mean that interviews cannot always be conducted openly. Civilians most likely to compromise the security of those working with KHRG may also be those who are most likely to present a positive view of the Tatmadaw, and express critical opinions of NSAGs that have been in conflict with Burma’s central government.

It is important to acknowledge that these limitations have restricted KHRG’s ability to make conclusions about all aspects of operations by opposition NSAGs or about potentially positive activities conducted by government actors. For this reason, this report avoids making conclusions that would be unsupported by the data set, including practices of government actors in areas where research was not conducted. Instead, this report focuses on sharing concerns raised by villagers that relate to events they experienced during the reporting period, and analysing those experiences in light of patterns previously identified by KHRG.

It is equally important to acknowledge that these research limitations do not call into question the veracity of documentation regarding practices by the Tatmadaw or other groups. While there is always a risk that individuals interviewed by KHRG might hold personal biases that cause them to provide exaggerated or inaccurate information, the verification practices described above are designed to prevent such inaccuracies from being reported by KHRG. Furthermore, the sheer volume and consistency of information gathered by KHRG during the reporting period, as well as over the last 20 years, minimises the potential for inaccurate or incorrectly identified patterns. Ultimately, the constraints faced by KHRG mean that there are unanswered questions about issues not present in the data set, on which further research needs to be conducted.

Table 1: Geographical spread of landmine incidents, May 2012 – January 2011

Footnotes:

[1] For Kw---'s previously unpublished interview, see Section III: Source Document: 2012/May/Pa'an/4.

[2] Ma Nu--- (shown in the back cover photo, right) subsequently gave birth to a healthy baby girl. She stepped on the landmine during January 2012 and, although part of her right leg had to be amputated, she now walks using a prosthetic leg. Her previously unpublished testimony, received by KHRG in May 2012, is included below in Section III: Source Document: 2012/January/Pa'an/1.

[3] KHRG research areas include some of all or parts of government-delineated Kayin and Mon states and Bago and Tanintharyi regions. The Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor has noted that Kayin state and Bago region are suspected to contain the heaviest landmine contamination in Burma and have the highest number of recorded victims. The Monitor also identified suspected hazardous areas (SHAs) in every township in government-delineated Kayin state; in Thanbyuzayat, Thaton, and Ye townships in Mon state; in Kyaukkyi, Shwekyin, and Tantabin townships in Bago region; and in Bokpyin, Dawei, Tanintharyi, Thayetchaung and Yebyu townships of Tanintharyi region; see Country profile: Myanmar Burma, ICBL Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor. Similarly, Dan Church Aid (DCA) which currently operates mine-risk education (MRE) programs and a prosthetic clinic in eastern Burma, has noted that, while verifiable data is difficult to gather due to infrequency of access, Burma experiences some of the highest mine accident rates in the world. DCA also notes that no de-mining programs are currently being pursued as new mines continue to be deployed by both government and NSAGs; see DCA Mine Action: Burma/Myanmar.

[4] Thaw Waw Thaw village, Noh Kay village tract, T'Nay Hsah Township, Pa'an District.

[5] An uncensored list of these Thaw Waw Thaw villagers names is provided below in Section III: Source Documents: 2012/May/Pa'an/1.

[6] Interviews with these eight villagers are provided below in Section III: Source Document: 2012/May/Pa'an/2 – 9.

[7] For three previously unpublished incident reports written by a community member working with KHRG and describing landmine casualties in Noh Kay and Htee Klay village tracts, see Section III: Source Document: 2012/April/Pa'an/1 – 3. For photos of villagers and livestock injured by landmines since the start of 2012, see photos below in Section II: B Movement restrictions resulting from landmines and Section II: F Landmine-related death and injury.

[8] Due to the volume of information received by KHRG, an additional 916 documents were received by KHRG in the reporting period but have not yet been processed and translated from the original Karen and so were not included in analysis for this report. KHRG information-processing involves the assessment of each individual piece of information prior to translation in order to determine quality and facilitate follow-up with community members where necessary.

[9] Two of these themes, namely B. Movement restrictions resulting from landmine contamination and G. Landmine use as a self-protection strategy were identified by KHRG; the other five were identified by the International Campaign to Ban Landmines (ICBL) which, in March 2012, requested field information received by KHRG since January 2011 relating to landmine incidents fitting within one of those categories.

[10] KHRG has received as-yet-unpublished documentation of forced labour incidents in Pa'an and Thaton districts during March and April 2012. Published reports describing forced labour in Toungoo and Dooplaya districts during 2012 can be found on the KHRG website; see "Ongoing forced labour and movement restrictions in Toungoo District," KHRG, March 2012; and "Abuses since the DKBA and KNLA ceasefires: Forced labour and arbitrary detention in Dooplaya," KHRG, May 2012.

[11] Plans for the development of a strategy to eliminate all forms of forced labour in Burma by 2015 were made explicit in the 2012 Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) signed by both the International Labour Organisation (ILO) and the Government of Myanmar on March 16th. Media groups subsequently reported statements by ILO officials suggesting that senior Tatmadaw commanders have indicated offending soldiers would be prosecuted under the penal code, rather than within martial law; see "Soldiers using forced labour to be prosecuted," Democratic Voice of Burma, May 9th 2012. For the full text of the MOU, see ILO Governing Body 313th Session, Geneva, 15–30 March 2012GB.313/INS/6(Add.).

[12] Due to the volume of information received by KHRG, an additional 916 documents were received by KHRG in the reporting period but have not yet been processed and translated from the original Karen and so were not included in analysis for this report. KHRG information-processing involves the assessment of each individual piece of information prior to translation in order to determine quality and facilitate follow-up with community members where necessary.

[13] Note that this transliteration system differs from the previous system used by KHRG, and as such the spelling of location names may be different. Note also that organisations developing the system agreed to continue using the spellings in common-usage for districts and townships, even where they do not match the new transliteration system.