Flight and displacement takes on many different forms in rural Karen areas. In SPDC-controlled villages, people find they can no longer survive adequately due to the demands for forced labour, the extortion, and the regime of restrictions they face in their daily lives, and leave their village for areas where the SPDC has less control. People in remoter areas are issued forced relocation orders and either move to the relocation site as ordered, or move into hiding near their village. Hill villagers find they can no longer farm because a new road lined with SPDC Army camps is pouring SPDC troops into their area, so they move into the higher hills. People already living in hiding in the forests have to flee to remoter areas when SPDC columns come too close. Villagers in forced relocation sites, cut off from access to their land, find they cannot survive and flee back to the area of their home village.

Flight and displacement takes on many different forms in rural Karen areas. In SPDC-controlled villages, people find they can no longer survive adequately due to the demands for forced labour, the extortion, and the regime of restrictions they face in their daily lives, and leave their village for areas where the SPDC has less control. People in remoter areas are issued forced relocation orders and either move to the relocation site as ordered, or move into hiding near their village. Hill villagers find they can no longer farm because a new road lined with SPDC Army camps is pouring SPDC troops into their area, so they move into the higher hills. People already living in hiding in the forests have to flee to remoter areas when SPDC columns come too close. Villagers in forced relocation sites, cut off from access to their land, find they cannot survive and flee back to the area of their home village. These are only a few examples.

When Karen villagers become displaced, they usually do not go far because they want to retain access to their fields and to familiar terrain. Sometimes the initial move is simply to the farmfield hut. People continue trying to plant and harvest, though covertly, and keep their rice supplies hidden in the forest. If SPDC troops become more active in their area, however, they may have to choose between a very mobile life near their fields, or moving further away from the SPDC presence. This forces them to find new land to plant, possibly to switch to a crop less visible than rice, and to diversify their livelihood, usually becoming more dependent on forest foods and cash crops. Obtaining rice becomes a major logistical dilemma. Some find they can no longer manage their survival, or encounter a disaster like the destruction of a crop or the loss of a family member, and must decide whether to continue the struggle or flee the area entirely.

Photos in the other sections of this report document the factors leading villagers in Karen regions to become displaced; the photos in this section illustrate the dynamics of displacement itself. This begins in Section 10.1, Life on the Run , by showing villagers on the move: the preparation for flight, the participation of family members in transporting their food, belongings, and each other, the separation and reunification of families and villages, and the ways villagers establish shelter and survival while keeping one step ahead of the SPDC columns sent to capture or kill them. Section 10.2, Food and Survival , then examines how displaced villagers change and diversify their livelihoods in the struggle to establish food security, and how they can survive for years under conditions which would appear to make survival impossible. Section 10.3, Health , continues by looking at the threats to displaced villagers' health and lives and how they deal with these: the exposure to diseases like malaria and dysentery, the lack of medicines and medical help due to the SPDC blockade against medicines entering the hills, the attempts to save the lives of landmine victims and critically ill villagers, and the sporadic assistance given by KNLA medics and mobile medical teams. Section 10.4, Education , looks at the disruption of education brought about by displacement, but more importantly at the villagers' intense efforts to continue schooling their children even when facing much more urgent threats to survival. What can appear initially as quixotic and misplaced efforts to teach children in the forest turn out to be important strategies to maintain the dignity, continuity, and community solidarity which are essential to long-term survival 'on the run'. Finally, Section 10.5, Flight to Thailand , looks at the factors which can lead people to the difficult decision to abandon their land, and the difficulties they face along the way.

The photos in this section were taken in Toungoo, Nyaunglebin and Papun districts in northern Karen State, Pa'an and Thaton districts in central Karen State, and Dooplaya district in southern Karen State. Most are from the northern districts, where the terrain makes it possible for tens of thousands of villagers to live in hiding and continue evading SPDC control. Some of the photos show villagers from southern Karenni (Kayah State) who have fled to these northern Karen districts to evade SPDC control. In Thaton, Pa'an and Dooplaya districts, SPDC control is more pervasive and there are fewer areas to hide, so villagers sometimes have little choice but moving to a forced relocation site or trying to escape to Thailand. Though numbers are impossible to accurately establish, the number of Karen villagers known to be displaced in the areas shown in these photos is in the hundreds of thousands.

10.1 Life on the Run

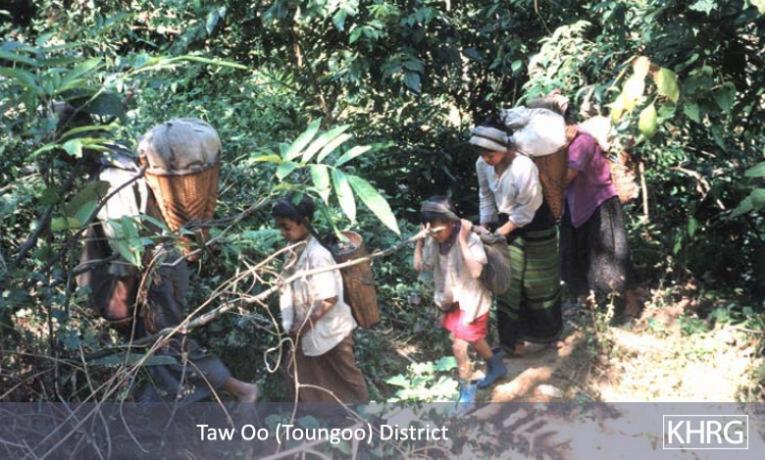

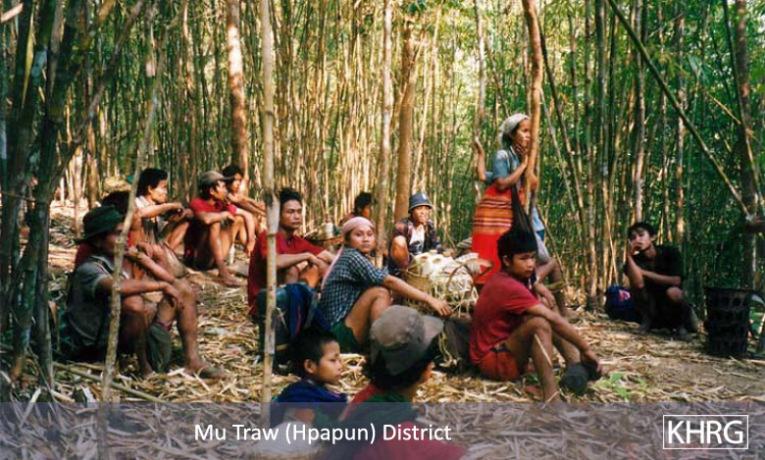

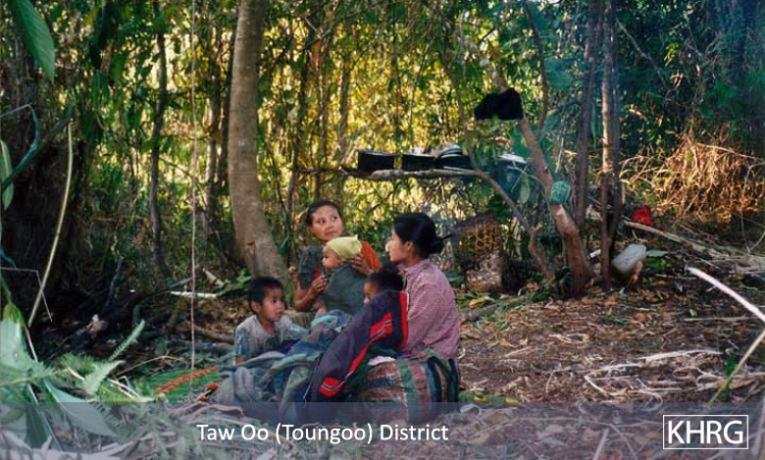

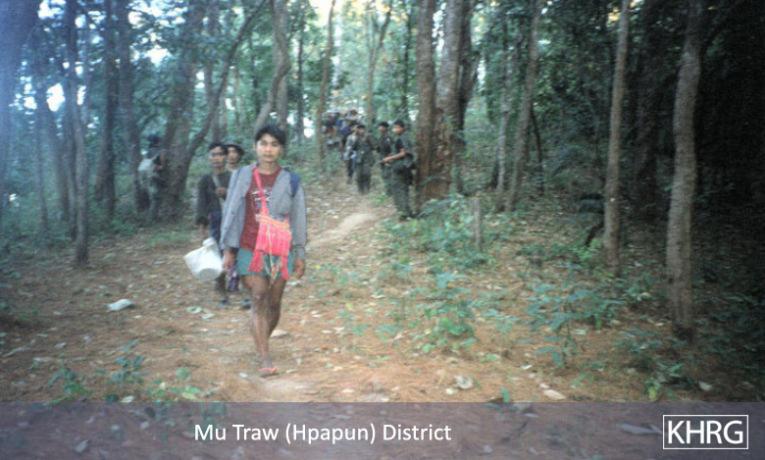

The photos below show people in the act of fleeing villages or on the move between IDP hiding sites to keep ahead of SPDC columns and beyond the reach of military control, and some aspects of how they survive this 'life on the run'. Their flight can be triggered by any number of factors. People flee to escape forced relocation orders (see photos 10-28 to 10-29 and 10-32 to 10-34 ); forced labour orders or roundups (photos 10-16 to 10-20 , 6-138 to 6-139 , 10-78 to 10-79 , 6-23 to 6-24 , and 10-107 to 10-113 ); arrest as 'relatives of Karen soldiers' (photos 10-102 , 4-14 , and 10-106 ); after villagers have been arrested, beaten, tortured or killed (photos 10-84 , 8-3 to 8-5 , 10-99 , and 2-20 ); when SPDC columns have come to destroy their villages (photos 1-7 to 1-12 , 10-5 to 10-6 , 10-30 to 10-31 , 10-43 to 10-46 , and 10-116 to 10-117 ); or when the presence of roads and SPDC Army camps has made life in their village no longer viable (photos 10-7 to 10-11 , 10-12 to 10-15 , 10-22 , 10-24 , and 10-88 to 10-93 ). Thousands of people over a large geographic area can be affected in a single SPDC operation, as demonstrated by the forced relocation campaign in southern Karenni (Kayah State) in early 2004, when Karenni villagers fled into northern Karen state and were pursued by SPDC columns, leading to additional displacement of northern Karen villagers (see photos 10-62 to 10-68 ).

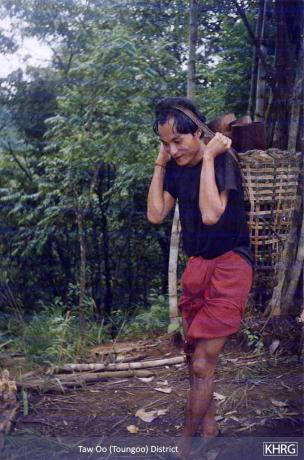

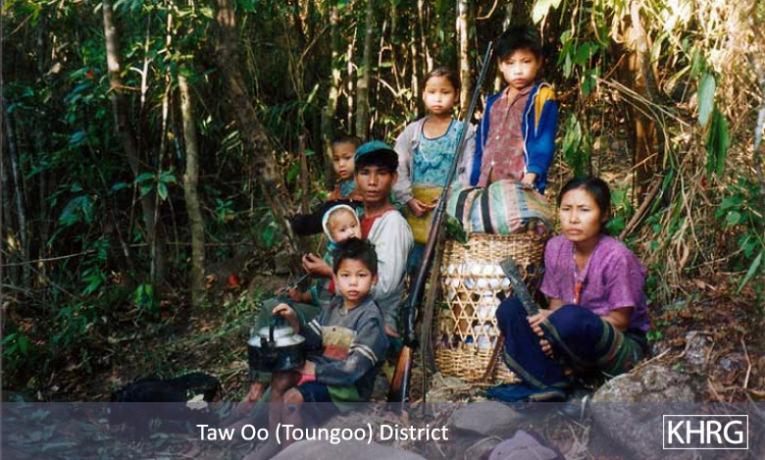

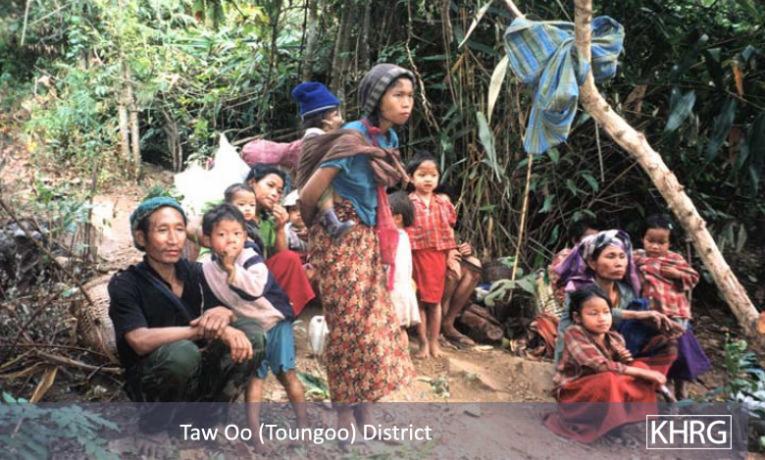

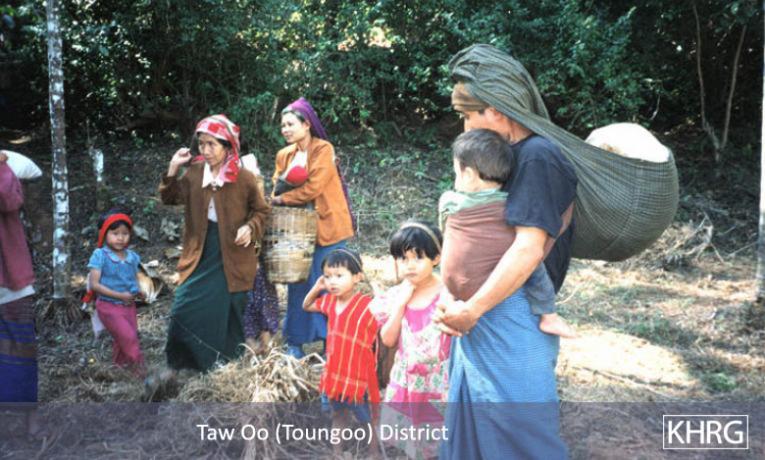

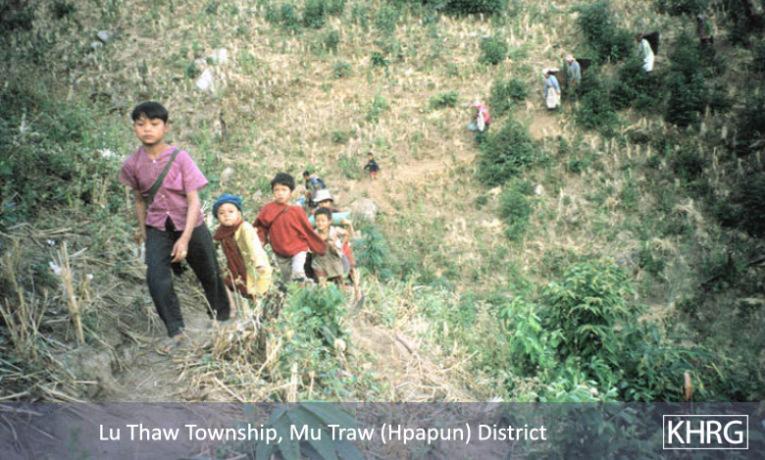

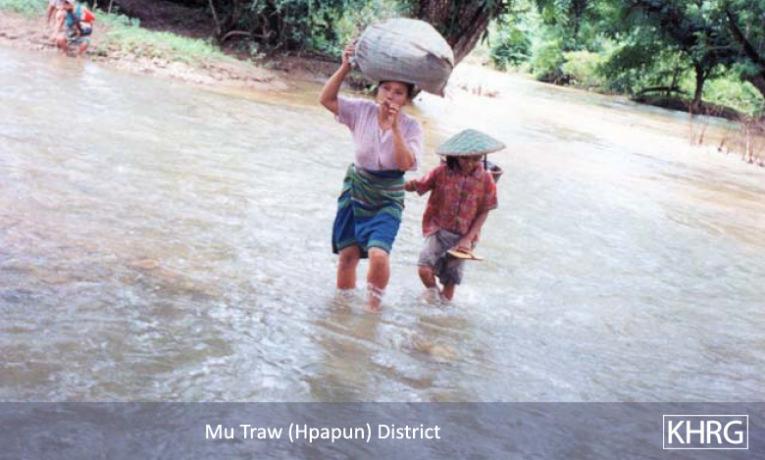

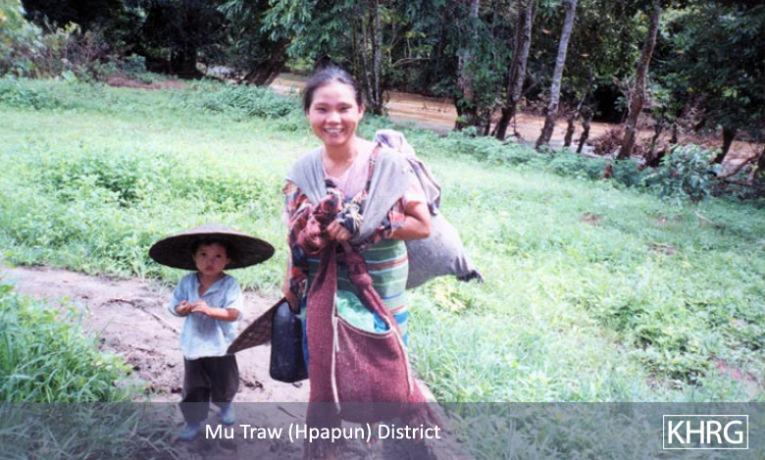

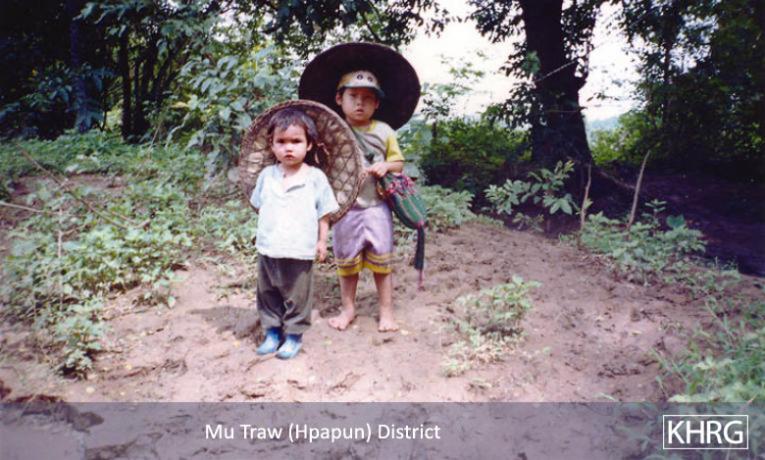

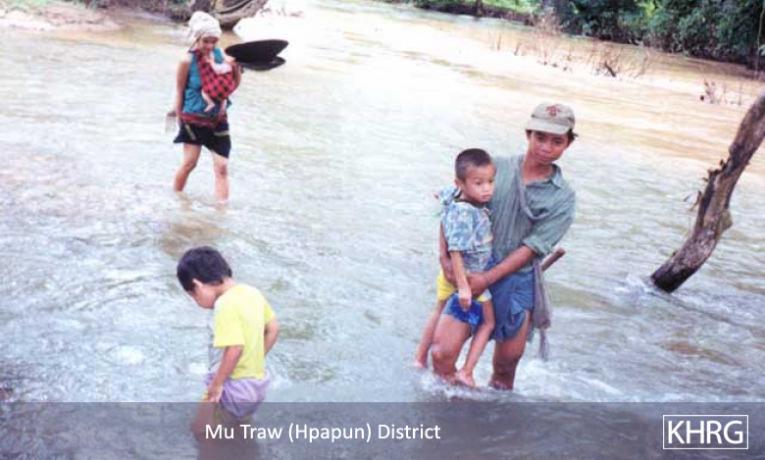

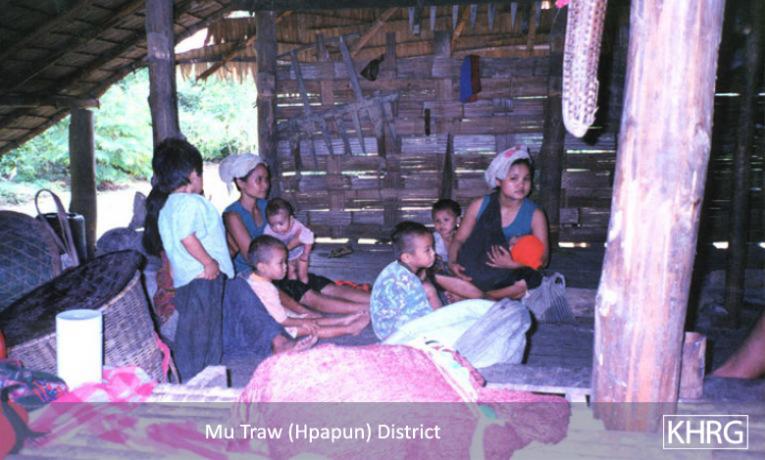

As can be seen in many of the photos below, everyone takes part in transporting needed food and belongings when on the move, even small children. Families and neighbours try to stay together, but families often become separated and must look for each other. When SPDC troops came to Naw K---'s village to threaten the villagers, most of the village men were away and the women had to transport everything into hiding, including the children (see photos 10-123 to 10-128 ). With the need for mobility, elderly and disabled villagers often become separated from the rest (see photo 1-4 ), or are left hidden somewhere while the others move on ahead, like the two elderly women in photo 10-61 .

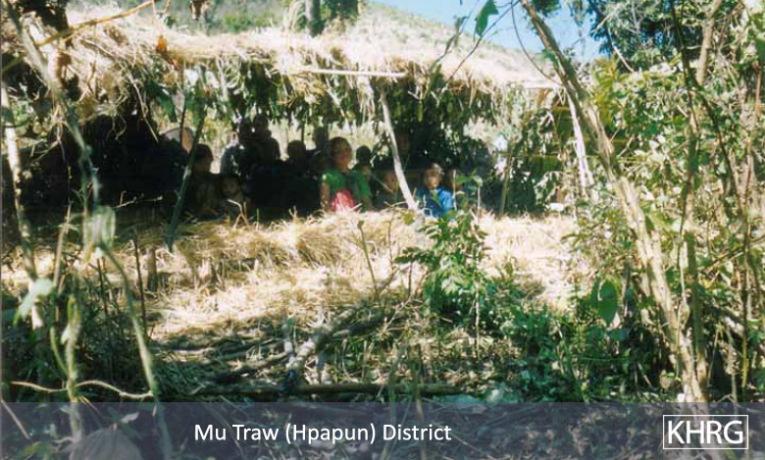

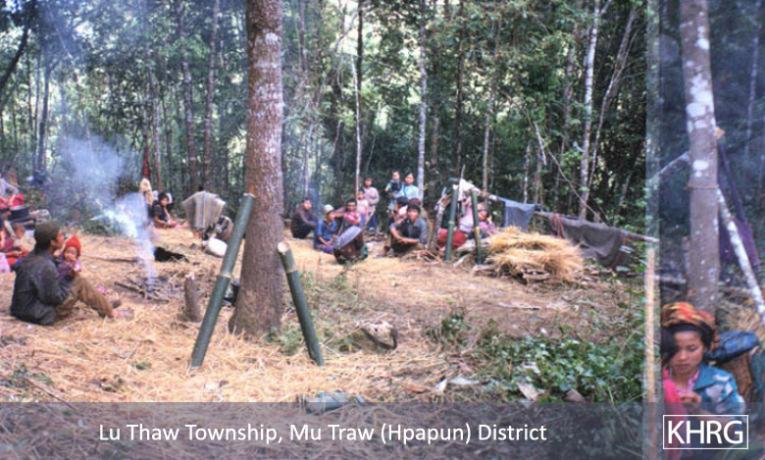

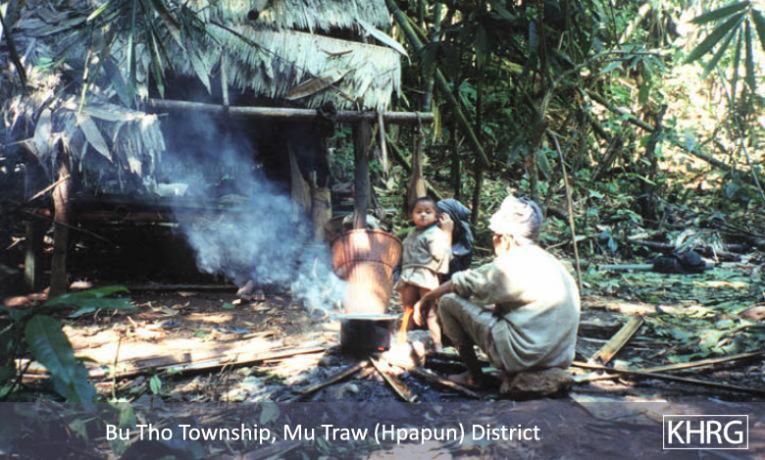

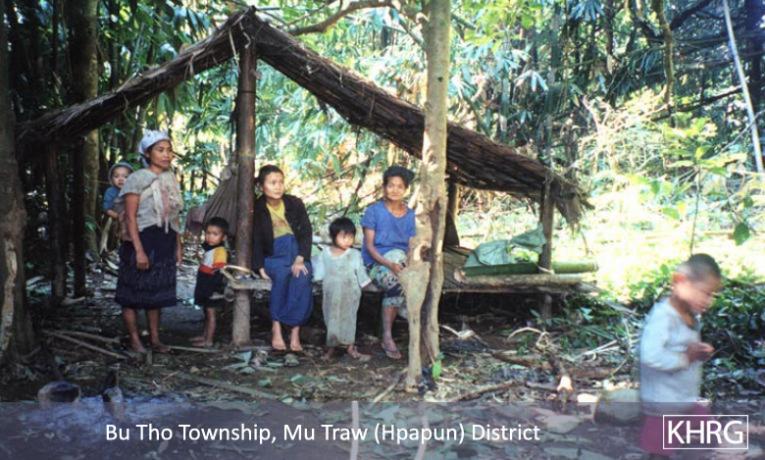

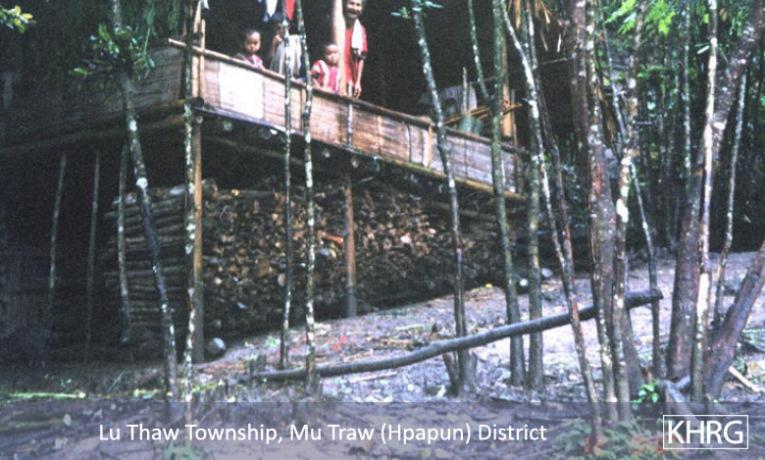

These photos also document some aspects of how villagers survive in these circumstances. For many, their experience of evading SPDC columns extends over the past two decades, so upon leaving their village they are usually very fast to organise and establish shelters, arrange shared food supplies, rudimentary schools and religious worship (see photos 1-7 to 1-12 and 1-13 to 1-16 ). Rather than panic and hunger, organisation and solidarity are the norm. Schools and religious activities are set up as quickly as possible because these provide continuity to village life and focal points for community togetherness while isolated in the forest; and children are still allowed the opportunity to play (see photos 9-9 and 10-15 ). Alternative foods readily available in the forest are prepared, and rice soup is used as a way to make the rice supply last longer (see photo 10-87 ).

In most cases displacement is not a matter of moving a long distance from the village and staying in a new area, but moving to people's farmfield huts or hidden sites near their village, returning to the village occasionally or even living there when SPDC columns aren't around (see photos 10-1 and 6-138 to 6-139 ). People remain constantly ready to move when SPDC columns approach, and return when they leave the area. For most displaced Karen villagers, displacement is not a shift to a different location so much as a shift to a more fluid and mobile lifestyle within their home area (see photos 10-16 to 10-20 and 10-103 ). Photos 10-131 to 10-133 show the type of terrain which surrounds many Karen villages, and the villagers' familiarity with its geography, flora and fauna make this ideal ground for living without being detected. Sometimes IDP hiding sites become well-established and almost like villages themselves (see photo 10-101 ). It is when the SPDC presence becomes constant and pervasive that people are forced to leave the area completely, and this is when things become most difficult because they lose access to their fields and to familiar land and streams.

As long as SPDC forces continue trying to depopulate the area, the villagers are at constant risk of being shot or executed by SPDC columns, especially when they return to their villages and fields (see photos 10-57 to 10-58 , 5-13 , 5-20 to 5-22 , and 5-26 to 5-27 ). Some have been shot at many times over their years of on-and-off displacement (see photo 5-74). Landmines are also a constant threat (see photo 9-14 ). Villagers act to reduce these threats by establishing two-way communication with KNLA units in their area, giving information on events in and around their village in return for information on SPDC movements. This is facilitated by long-standing relationships between village leaders and local KNLA officers, who do not rotate between regions like SPDC officers do, and by the fact that many villagers have relatives in the KNLA. When SPDC columns are in hot pursuit, villagers sometimes call in the KNLA for protection (see photos 10-40 to 10-42 , 10-56 , and 10-57 to 10-58 ). Some KNLA units have even given IDPs homemade landmines to use in protecting their hiding sites, though as photo 11-44 shows this can create more suffering than protection.

For many villagers the cycle of flight, rebuilding, and flight again has been ongoing for most of the past twenty years, since SPDC troops first tried to extend state control into their region. SPDC columns force them to flight, then seek out and destroy their hiding sites (see photos 10-59 to 10-60 ). With time, they may be able to gradually re-establish their village when SPDC officers change (see photo 10-1 ) or when the column focuses on another area, only to have their rebuilt homes burned and destroyed again. Photos 10-115 and 10-119 to 10-121 show villages which have been repeatedly burned over recent years, and the same Karenni villagers who fled to Karen State to escape forced relocation in 2002 (see photo 10-122 ) had to flee to Karen State to avoid forced relocation again in 2004 (see photos 10-62 to 10-68 ). Rank and file SPDC soldiers may sometimes feel remorse for this, as shown by the note scrawled in an abandoned village in photos 10-28 to 10-29 ; but the officer's note shown in photos 10-80 to 10-81 calling on displaced villagers to submit to the SPDC indicates that there is little likelihood that forced displacement will end soon.

10.2 Food and Survival

Rice is the staple food in Karen villages, and after it is harvested and dried it is kept in small storage barns. These were traditionally scattered around the village, but decades of military looting and abuse has changed the tradition and rice barns are now hidden deep in the forest. The SPDC calculates that if villagers can be cut off from their food supply they will have no option but to move into state-controlled areas and submit to the regime. SPDC forces trying to clear people out of areas therefore deliberately target food supplies, taking or destroying whatever rice the villagers have in their village, looting the village of livestock (see photos 7-82 to 7-84 ), seeking out and destroying rice storage barns in the forest (see photos 10-139 , 7-17 , 7-24 to 7-25 , and 7-27 to 7-29 ), and sometimes landmining the ruins of rice barns in case villagers return to see what they can salvage (see photos 11-20 to 11-24 ). Fruit, betelnut and other cash crop plantations are also destroyed (see photo 7-18 ). To prevent the villagers who go into hiding from producing a crop, SPDC battalions hunt out and destroy their hiding sites (see photos 2-31 to 2-36 and 7-35 to 7-36 ), but they actually spend more of their time trying to cut off the villagers' ability to produce food. This is done by sending columns in February and March to find hill fields where the bush has been cut for planting but not yet burned off; by prematurely burning these fields, they prevent a proper burn later and the villagers cannot plant a decent crop (see photos 7-20 to 7-23 ). In September and October columns are sent again, this time to uproot rice which is ripening before the harvest (see photos 7-32 and 7-33 to 7-34 ); sometimes they cannot uproot it all, so they lay landmines before leaving. Harvest time in November to December is usually when the most soldiers come (see photos 1-28 to 1-32 ), because then they can spot groups of villagers in the golden hillside fields from a long distance, making it easy to capture or shoot them (see photos 5-23 to 5-25 , 5-31 to 5-32 , and 5-33 to 5-40 ). Moreover, if villagers have to flee right at harvest time, the crop will go to seed or be taken by insects and animals.

People who move from their home areas to SPDC-controlled areas or forced relocation sites are usually cut off from their home fields, which rapidly degenerate (see photos 7-59 to 7-60 ). Most of them have to find ways to survive by doing paid day labour for farmers or others, supplemented by foraging whatever they can. Combined with the regular forced labour now demanded of them, many find it too difficult to survive and end up fleeing back into their home areas despite the risks.

Those who refuse to relocate become displaced in their home area. Initially they try to harvest the crop currently in the fields and to retrieve whatever rice they have stored around the village (see photos 1-5 to 1-6 , 1-17 to 1-19 , 1-28 to 1-32 , and 1-44 to 1-51 ). Some manage to keep using the rice in their hidden barns, but if these are found by SPDC forces there may be little left that can be salvaged. These sources can only provide food for a limited time. Many people have to abandon their fields because they are too near SPDC camps or roads (see photos 7-39 , 7-49 , and 7-43 ). Roads are extremely dangerous to cross or to move along because of the likelihood of being sighted by SPDC patrols, and this frequently leads to people being cut off from their fields, other family members, and access to medical help (see photos 6-133 and 7-40 to 7-41 ). If SPDC troops operate more than sporadically in the area, the home fields may have to be abandoned (see photos 7-37 and 7-45 to 7-46 ).

Displacement thus forces people to change their ways of farming rice and also to find alternative forms of livelihood. If it is no longer possible to cultivate large hillside fields due to SPDC troop activity, villagers may clear small patches within several fields and divide their crop between these small patches. As rice fields are still exposed, villagers have to work quickly when SPDC columns are not nearby (see photos 1-22 and 7-61 to 7-62 ), sometimes harvesting by night or with KNLA guards. Many begin cultivating small-scale cash crops which can be grown at hidden locations in the forest, like cardamom (see photo 7-44 ). People also increase their reliance on forest foraging, drawing on their knowledge of local forest products (see photo 9-8 ). The villagers in photos 10-134 to 10-138 have switched their livelihood and now produce roofing thatch to sell. To exchange cash crops or money for much-needed rice, people sneak into SPDC-controlled villages to buy rice and carry it back into the forest (see photo 7-63 ). The riskiness of this is illustrated by photos 5-58 to 5-60 , where villagers taking betelnut to market with a KNLA escort were attacked by SPDC troops and shot. An alternative, though also dangerous, is to arrange with traders in SPDC-controlled villages to hold temporary 'jungle markets' where displaced villagers can exchange cash crops and money for rice, dry goods, medicines and other needs (see photos 7-55 to 7-57 ).

The difficulties involved require that every family member become actively involved in food production, which also means that every family member is exposed directly to being shot on sight, stepping on landmines, and other dangers. Some families have already lost family members, which only puts a greater burden on the others (see for example photos 5-31 to 5-32 , and Sections 8.3 [ Women, Livelihoods and Displacement ] and 9.4 [ Orphans ]). Villagers also take measures to make food supplies last longer, such as eating rice porridge instead of steamed rice (see photo 10-141 ), and rely heavily on forest foods they would eat less in the village, like bamboo shoots, banana trees, and various roots. Some of these, like klih roots, are semi-toxic and require a lot of processing and would not generally be eaten in the village, but become foods of last resort in the forest. For those who cannot produce enough, others always share what they can. Karen relief teams also move through these areas with aid to improve food security (see photos 7-85 to 7-87 ), but they are under-resourced and can only reach a minority of IDPs on a regular basis.

10.3 Health

Once they are displaced, villagers are much more exposed to dangers such as illness, landmines, and being shot by SPDC soldiers, yet they have very little access to health care. IDPs generally cannot seek medical help in SPDC-controlled towns and villages, either because there is too much danger of arrest or because the treatment is far too expensive (see photo 8-16 ). If they are in hiding in the hills, medical help from SPDC-controlled areas cannot come to them because the SPDC enforces a blockade against medicines and medical help going into areas they are trying to depopulate. Most displaced villagers therefore only have access to traditional remedies, which often prove insufficient (see photos 8-20 , 8-10 to 8-12 , 10-146 , 8-18 to 8-19 , and 9-25 ), or sometimes to KNLA and Karen relief medics (see text below).

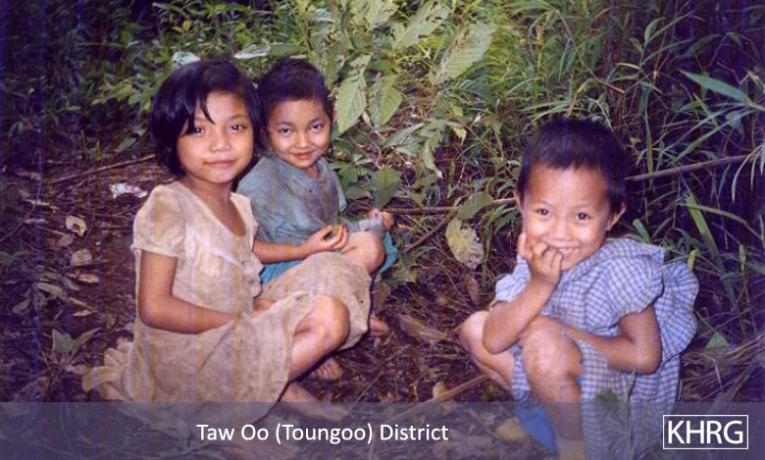

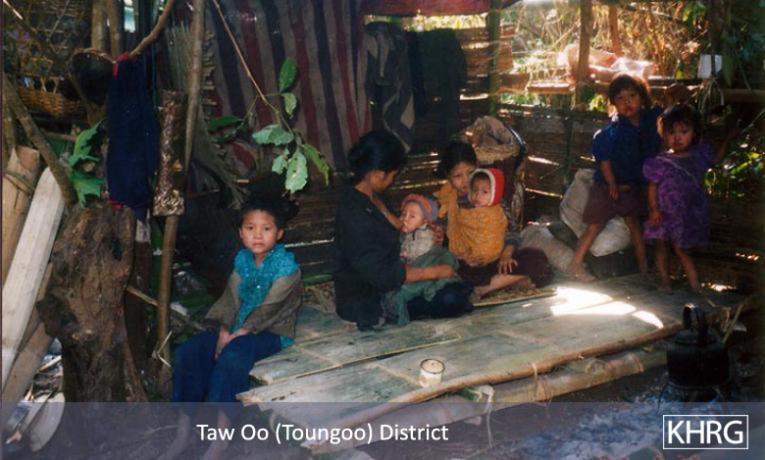

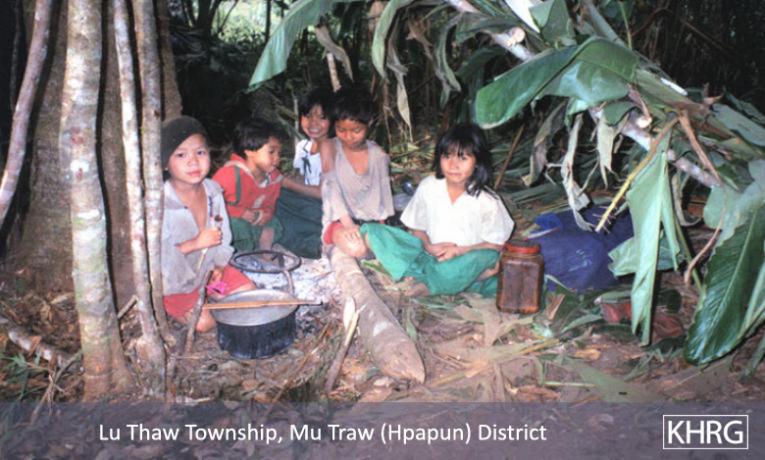

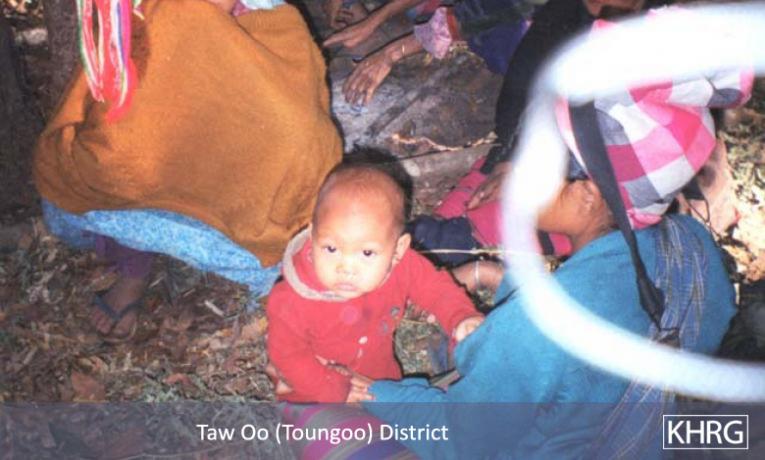

Disease and malnutrition kill more displaced Karen villagers than are killed by SPDC troops. Once displaced it is difficult to obtain a stable supply of food good enough to avoid malnutrition, and if people are in a forced relocation site or far from their village they are forced to rely on unknown and often unclean water supplies. Displaced villagers are exposed to malaria, dysentery, typhoid, tuberculosis, dengue fever, encephalitis and a host of other illnesses, infections and parasites, and often also fall prey to oedema, goitre, and other conditions brought on by dietary deficiencies. Frequently forced to sleep in the open, they are very vulnerable to mosquito-borne illnesses like malaria, dengue and encephalitis. Children (see photos 10-3 to 10-4 ), the elderly, and pregnant and nursing women (see photos 8-10 to 8-12 ) are the hardest hit groups. Many women fall ill because they are weakened by the multiple burdens of producing and foraging for food, caring for children, and being on the move, increasing their vulnerability to all of the threats already mentioned (see photos 8-8 and 8-9 ). Many mothers give birth in the forest in unsanitary conditions and with little or no help (see photos 8-15 , 8-17 , and 8-24 to 8-25 ). Maternal and child mortality and morbidity are both extremely high (see photos 8-13 and 8-18 to 8-19 ).

There is also the constant danger of being shot by SPDC columns (see Section 5, Shootings and Killings ) or stepping on landmines (see photos 11-11 and 11-12 to 11-15 , and other photos in Section 11 [Landmines] ). Landmines are laid by all armed forces in these areas and are seldom removed. KNLA forces are the only ones to try to inform the villagers of which pathways are mined, but the information they provide is insufficient and many villagers still detonate their mines. Villagers who survive shootings or stepping on mines carry the resulting disabilities for their entire lives, particularly because proper treatment is unavailable (see photos 11-48 to 11-49 and 5-77 ); while more still suffer the effects of previous forced labour (see photo 10-147 ) and other SPDC abuses.

Apart from traditional remedies, the only treatment available to most Karen IDPs comes from KNLA medics or mobile medical teams sent by local relief organisations (see photos 10-143 , 10-144 to 10-145 , 8-8 , 9-23 , 8-9 , 9-24 , 10-149 to 10-150 , and 10-151 to 10-153 ). These medics cannot always reach IDPs in all areas (see photos 8-14 and 11-48 to 11-49 ) and their presence is sporadic, so people with serious wounds such as landmine victims must usually be carried for several days to reach a medic, dodging SPDC columns and landmines all the way (see photos 11-16 to 11-18 and 11-47 ). Even if they can be reached before the patient dies, these medics are often short of medicines and dressings. Photos 11-16 to 11-18 , for example, show an amputation being performed without anaesthetic on a Karenni landmine victim, who had already been carried several days from southern Karenni (Kayah State) to northern Karen State to reach medical help.

10.4 Education

Education is highly valued in Karen communities, not for material reasons but as a way of preserving culture and language, reinforcing identity, and strengthening dignity and community solidarity. Despite the fact that completing school in a Karen village brings few or no career or material advantages, people put a lot of effort and resources into village schools and see them as a focal point of community life (see photos 10-157 to 158 and 9-30 ). When communities become displaced, schooling is not abandoned to make way for more immediate survival needs; instead, it is treated as more important than ever, and efforts are made to immediately establish rudimentary schools even while people are still living on the bare ground of the forest under banana leaves (see photos 10-154 to 10-156 , 1-52 to 1-55 , 10-7 to 10-11 , and 9-26 ).

Displaced villagers in hiding are usually widely scattered in groups of a few families, so they sometimes arrange to set up a single school somewhere and send their children there (see photos 9-35 and 10-160 to 10-161 ). Most of these schools are at primary level, because the local teachers available have no more than primary education themselves (see photo 9-37 ). They have only whatever notebooks, pencils and chalk the parents can afford to buy (see photos 9-29 , 9-30 , and 9-33 ). Students wanting to continue to middle and high school must either travel to one of the few KNU higher-level schools located in areas where there is little SPDC activity (see photos 9-27 to 9-28 ), or go to a refugee camp in Thailand. Some parents send their children to refugee camps for the school season, while remaining in hiding themselves near their home village; the students then return to help their parents during the March to May school holidays. Some children, however, are needed constantly to help their families produce enough food to survive and cannot attend even primary school (see photo 9-34 ), or have to quit before finishing because of some disaster like the loss of a family member (see Section 9.4 [Orphans] ).

Recognising the importance of village schools to Karen identity and village solidarity, the SPDC tries to destroy them and refuses to allow any schooling to exist outside the state-controlled system. Non-state schools are burned if found (see photos 1-52 to 1-55 ), whether in villages or in IDP hiding sites. Whenever SPDC columns are nearby the villagers have to close their schools, so some of them can only remain open sporadically (see photos 9-27 to 9-28 , 9-29 , 9-31 , 9-32 , 9-36 , and 9-38 ). Yet despite the risks, villagers have stated to KHRG that education will remain a priority for them if only to prevent the SPDC from succeeding in its attempt to dehumanise them and destroy their communities.

10.5 Flight to Thailand

Most Karen villagers feel a very strong bond to their village and their land, and would suffer almost any deprivation rather than leave it. Sometimes, however, they can be pushed into a state where they no longer think they can survive. This can be caused by the construction of an SPDC camp too near their fields, the sudden destruction of their entire food supply, the loss of family members due to disease or violence, or other disasters, which sometimes operate in combination or with cumulative effect. For some people this occurs while they are still in their village (see photos 10-174 to 10-181 ), for others while they are evading SPDC forces by living in the forest (see photo 10-173 ); it can be sudden (see photo 3-3 ), or a gradual accumulation of suffering over years (see photos 10-162 to 10-163 ). When this point is reached, most people opt to flee across the border rather than submit to SPDC control, forced labour and impoverishment by moving into state-controlled areas. When possible, their flight is temporary (see photos 10-164 to 10-169 and 10-170 to 10-172 ), but if SPDC forces establish a consistent presence in their home area they may not be able to return.

Fleeing to Thailand is difficult and dangerous. In most areas, the terrain is mountainous and polluted with landmines, the villages along the way may have already been destroyed eliminating the possibility of any help, and fleeing villagers caught by SPDC columns are treated as active rebels (see photos 5-67 to 5-72 ). Once the border is crossed, the refugees must find their way to one of the few remaining refugee camps undetected, because if they are caught by Thai soldiers, paramilitaries, police or forestry officials en route they are summarily and forcibly repatriated (see photos 10-162 to 10-163 ). Finally, those who reach refugee camps often have to hide from Thai camp guards and become 'unregistered' refugees during periods when the Thai government has declared that no new refugees are to be allowed – which is usually when it is seeking to improve ties and trade with the SPDC. Though international NGOs provide food and medical care in the refugee camps, the camps are overcrowded, food is strictly limited by order of the Thai government, and growing food, working outside the camp, and foraging are restricted or prohibited, as part of a Thai policy to encourage refugees to repatriate by making life in the camps unattractive. The camps are also situated in areas vulnerable to cross-border attack by SPDC forces, and some are in areas prone to floods and landslides which periodically kill some of the refugees (see photos 10-182 to 10-194 ). Life for Karen refugees should therefore not be seen as safe, secure, or happy. The vast majority of them would certainly prefer to return home, but their decision not to do so despite all the pressure applied by Thai authorities and UNHCR only demonstrates the difficulty of the situation they have fled.

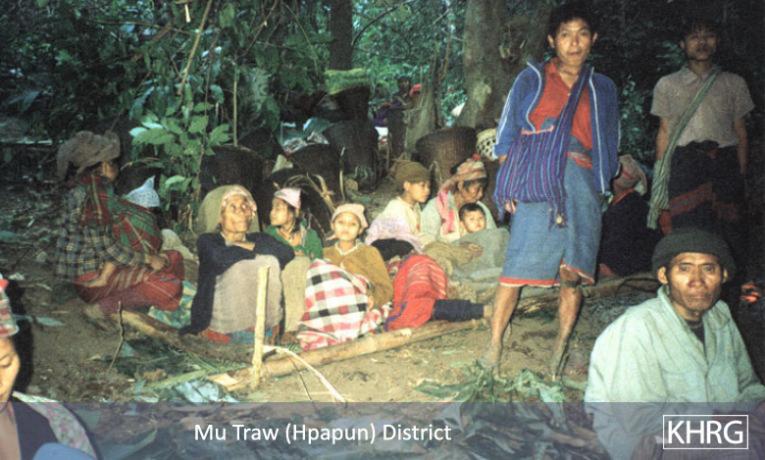

Photo #10-1: Villagers from N--- village in Dweh Loh township, Papun district build new houses in their original village site in February 2005. For several years they have moved between this site and hiding sites in the forest to avoid SPDC forced relocation orders, but early in 2005 they were told by the local SPDC Army commander that they would be allowed to stay in the original site once again. Such orders, however, are unreliable and can change as soon as the commanding officer changes. [Photo: KHRG researcher] Photo #10-2: Villagers from S--- village, Tantabin township, Toungoo district, hiding in the forest the night of January 17 th 2005. They fled their village because Commander Chan Nyein Tha and his soldiers from SPDC IB #73 Column 1 came to the village, arrested two villagers there and killed them. [Photo: KHRG researcher]

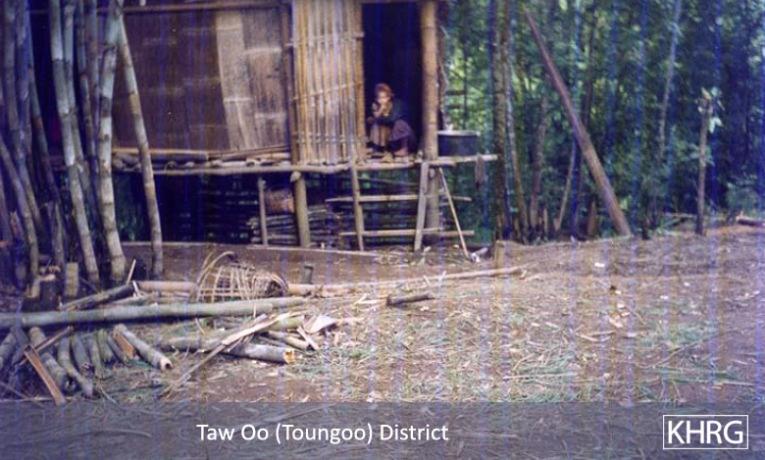

Photos #10-3, 10-4: Villagers from M--- village in Toungoo district, who fled to the forest on December 18 th 2004 when a column from SPDC LIB #590 (Battalion Commander Ko Ko Oo commanding) based at Tha Aye Hta marched through several villages in the area. The village headman said they would have faced detention and forced labour if they had stayed, so all villagers fled. Photo #10-3 shows a temporary hut in the forest, and photo #10-4 shows a girl from the village who has been suffering for days from high fever. [Photos: KHRG researcher] Photo #1-4: On November 19 th 2004 a KHRG researcher encountered Saw P---, age 75, along a path in the forest in Shwegyin (Hsaw Tee) township, Nyaunglebin district. He said he was searching for his family because when an SPDC Army column approached their village they fled and became separated. Families usually flee approaching columns in this region because SPDC troops usually detain villagers as porters or suspected rebels, so family separation is often a problem. [Photo: KHRG researcher]

Photos #1-7, 1-8, 1-9, 1-10, 1-11, 1-12: Several days after the burning of Klaw Lu village (see above), the SPDC column was still in the area so the villagers remained hidden, cooking rice only at night so smoke from cookfires would not give them away. Photos 1-7 and 1-8 show some of the children settling in for the night. Photo 1-9 shows 60-year-old Pi K--- and her husband. They have no children and were unable to carry rice themselves while fleeing, so they had no food and had to share that of others. In photo 1-10 , a Christian pastor who was visiting the area when the villages were invaded gathers the Christian villagers in the forest for a worship service. Naw P---, 46 ( photo 1-11 ), fell sick in the forest and was cared for by other villagers. Naw D---, age 75 ( photo 1-12 ), is blind; when the villagers fled one of her sons (shown here) carried her while the other carried food. All of these photos were taken on November 20 th and 21 st 2004, within three days of the arrival of the SPDC column in the area. [Photos: KHRG researcher]

Photos #1-13, 1-14, 1-15, 1-16: By November 21 st 2004, three days after SPDC LIB #589 had entered the area, the villagers from Klaw Lu, K'Hee Day and Khaw Hta were weaving thatch for roofing ( photo 1-15 ) and building shelters. Saw G---, 40, was building a shelter along with his pregnant wife ( photo 1-13 ); he said their house in Khaw Hta had been burned by LIB #589. Small children and pregnant women were given priority for the first shelters built. [Photos: KHRG researcher]

Photos #10-5, 10-6: In late 2004 a group of Karenni villagers fled southwestern Kayah State because their houses were burned and looted by SPDC LIB #428 and the KnSO [Karenni Solidarity Organisation, a former battalion of the Karenni resistance which broke away and now works with the SPDC (for more information see Enduring Hunger and Repression [KHRG #2004-01, September 2004]) , and are now displaced in northern Karen State. These photos show Naw K---, her 3 children, and her hut in the forest of northern Papun district in October 2004. Her husband was shot dead by a combined column of SPDC LIB #428 and KnSO soldiers in Kayah State. They crossed into Karen State and sought refuge in Kaw Lu Der village tract of Papun district, but SPDC troops looted their belongings again there, so this is their second hiding place. Even here they are not safe, as Karen villagers in this area are shot on sight by SPDC columns. [Photos: KHRG researcher]

Photos # 10-7, 10-8, 10-9, 10-10, 10-11: Internally displaced villagers in eastern Toungoo district, September 2004. These people fled villages near the Toungoo-Mawchi vehicle road near the Karen/Kayah State border due to the heavy SPDC military presence along the road. Naw M---, age 31 ( photo 10-8 ) lost her husband when he was arrested and killed by SPDC IB #26. Naw S---, age 19 ( photo 10-9 ), fled after troops from Light Infantry Division 55 burned her village. The photos show the area in the forest where they now stay in makeshift shelters. Photos 10-10 and 10-11 show the makeshift primary school they have established for their children in a nearby farmfield hut. Establishing makeshift schools is often one of the first priorities of displaced villagers because it maintains a sense of dignity, community and continuity. [Photos: KHRG researcher]

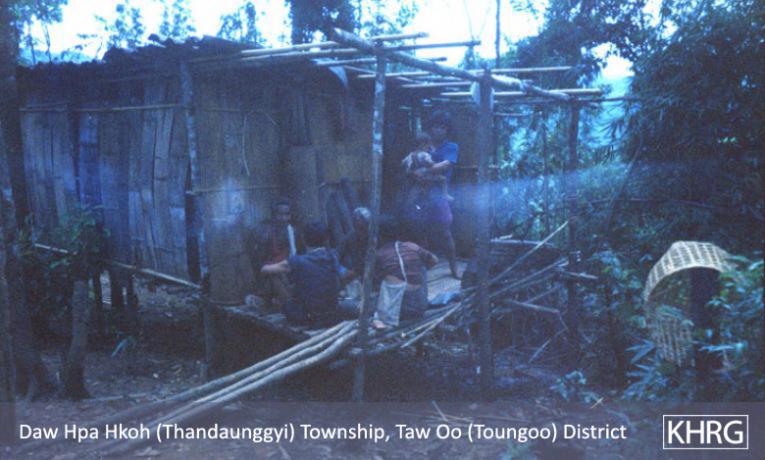

Photos # 10-12, 10-13, 10-14, 10-15: Displaced villagers from Sho Hser village, along the Toungoo-Mawchi vehicle road on the Karen/Kayah State border, in August 2004. They had to flee their village due to increasing SPDC militarisation of the area along the road, and now live in hiding here in the forested hills. Photos 10-12 and 10-13 show some of their forest shelters. In photo 10-14 , a man carries drinking water from the stream in several hollow segments of bamboo. For children, the need to play still continues ( photo 10-15 ). [Photos: KHRG researcher]

Photos #10-16, 10-17, 10-18, 10-19, 10-20: Photo 10-16 shows part of K--- village in Tantabin township, Toungoo district, in August 2004. Villagers here say that whenever SPDC patrols approach their village they have to flee into the forest to avoid being taken for forced labour or otherwise detained. As a result they have difficulty farming, breeding livestock, and travelling around the area. Photos 10-17 and 10-18 show them heading through the forest in January 2004, one of the many times they have had to flee. In February 2004 they were still hiding in rough shelters in the forest (photos 10-19 and 10-20 ) because SPDC troops were still active around their village. Though living in their village part of the time, they consider themselves displaced. [Photo: KHRG researcher]

Photo #10-21: Naw S---, 40, and her 9 year old son Saw B--- are from S--- village in the hills of Tantabin township, Toungoo district, but due to SPDC militarisation around their village they now live in hiding in the forest in this simple hut. This photo was taken in August 2004. [Photo: KHRG researcher]

Photo #10-22: A section of the road from Pwa Ghaw to Saw Hta in Papun district ( see map ), which SPDC forces bulldozed through the forest to give them a firmer foothold in the Papun hills. Since its completion in 2000, this road has made life much more difficult for villagers and displaced people in the area. Those with fields near the road route have had to abandon them, and those needing to cross the road to reach fields or food supplies take a risk of being shot on sight by SPDC patrols that frequently move along the road. As a result the entire area near the road has been largely depopulated. There is speculation that this road is also intended to facilitate SPDC militarisation of the Salween River to protect construction of the planned Salween dams. [Photo: KHRG researcher]

Photo #10-23: When this photo was taken in June 2004, these women and children from S--- village in Than Daung township, Toungoo district, had just fled into the forest to escape SPDC troops. Here they have gathered in the rudiments of one of the first shelters they are building. [Photo: KHRG researcher] Photo #10-24: These villagers from B--- village, Bu Tho township, Papun district left their village after SPDC troops set up a camp along the vehicle road nearby in April 2004. With the camp on the road, they said that they can no longer dare travel to town to get food or work farmfields anywhere near the road. In Karen hill areas, roads increase mobility for the Army but decrease it for villagers. [Photo: KHRG researcher] Photos #10-25, 10-26, 10-27: Families fleeing B--- village in Tantabin township, Toungoo district, when SPDC LIB #117 (Battalion Commander Aung Thein Oo commanding) began patrolling their home area in February 2004. Photo 10-25 shows a family resting during their flight, surrounded by all the belongings they could carry. In photos 10-26 and 10-27 , the villagers have reached a temporary hiding site and are beginning to settle in. [Photos: KHRG researcher]

Photos #10-28, 10-29: These photos show a message of remorse written in charcoal on an abandoned villager's house by an SPDC soldier from the unit that forced them to relocate. When IB #39 ordered K--- village in Toungoo district to relocate, the villagers fled into the hills instead and had not yet returned when this photo was taken in February 2004. On the abandoned house of a girl he clearly liked, this soldier wrote: "To Ma C---, full of remembrance I have written this note. When I arrived at little sister's [your] village, I imagined little sister. [I] Remember the place where [I saw you] wearing [your] skirt. But I'm sorry that we can't do anything. I am sorry. That is all. IB #39, H---." Photo 10-28 shows the entire note; photo 10-29 focuses on the second half more clearly. [Photos: KHRG researcher]

Photos #10-30, 10-31: Karen villagers in Than Daung township, Toungoo district, fleeing on January 24 th 2004 after SPDC Light Infantry Division #55 troops had burned their village at Htee Hsa Per. They had to grab whatever they could and run as the troops entered the village. See also photos 10-32 through 10-34 . [Photos: KHRG researcher] Photos #10-32, 10-33, 10-34: In January 2004, SPDC troops from LIB #509 (under Light Infantry Division #55) burned and forcibly relocated several villages in Than Daung township, Toungoo district (see photos 10-30 and 10-31 ). Rather than wait for their turn, the people of nearby T--- village fled their homes into the forest. Photo 10-32 shows part of the village just after its abandonment. Saw P---, 61, and his wife ( photo 10-33 ) and mothers with small children ( photo 10-34 ) were among those living on the ground under forest lean-to's in these photos taken in January 2004. [Photos: KHRG researcher]

Photos #10-35, 10-36, 10-37, 10-38: On January 15 th 2004, a column from SPDC IB #94 moved into the area of H--- village in Than Daung township, Toungoo district, so the villagers fled to the forest en masse . [Photos: KHRG researcher] Photo #10-39: A mother with a newborn infant takes a rest while fleeing into the forest with other villagers on January 16 th 2004. She is from K--- village in Tantabin township, Toungoo district. [Photo: KHRG researcher] Photos #10-40, 10-41, 10-42: Villagers fleeing K--- village in Lu Thaw township, Papun district, on January 21 st 2004 as an SPDC Army column from Light Infantry Division #55 enters their area. In photo 10-40 an elderly villager struggles with a load, while the KNLA officer on the radio behind him monitors the column's movements to make sure the villagers don't walk into an ambush. Photo 10-41 shows a group of villagers resting in the forest along their way, and in photo 10-42 they have reached a shelter in the fields camouflaged by rice straw. Meanwhile, the SPDC column saw and killed villager Saw Kloh Po Heh from the neighbouring village of K'Leh Loh (see photos 10-43 through 10-46 below). [Photos: KHRG researcher]

Photos #10-43, 10-44, 10-45, 10-46: Villagers flee K'Leh Loh village in Lu Thaw township, Papun district to escape an approaching column of Light Infantry Division #55 in January 2004. The column entered their village, burned their paddy storage barns, looted their houses, and killed villager Saw Kloh Po Heh. [Photos: KHRG researcher]

Photos #10-47, 10-48, 10-49, 10-50, 10-51, 10-52, 10-53, 10-54, 10-55, 10-56: Villagers throughout Lu Thaw township of Papun district fled their villages as mobile SPDC columns sought to catch them in their villages in January 2004. The people of K--- village fled on January 8 th (photos 10-47 and 10-48 ); from L---, M---, and T--- villages also on January 8 th (photos 10-49 through 10-51 ); from P--- village, on January 11 th ( photo 10-52 ); from K--- village on January 18 th ( photo 10-53 ); and from H--- village on January 18 th (photos 10-54 and 10-55 ). Photo 10-56 shows some of the displaced villagers who have gathered at one hiding site arriving to meet with local KNLA officers to get information on SPDC movements and to request medicine for the sick. [Photos: KHRG researcher]

Photos #10-57, 10-58: These internally displaced villagers live in an area of Papun district where three columns of SPDC Light Infantry Division #55 are active. On January 18 th 2004, they went to collect some of their food stored back at their home village of T---. On the way back to their hiding site, a patrol from SPDC Light Infantry Division #55 sighted them and opened fire on them, forcing them to drop many of their loads and run. A cattle trader with the group had a walkie-talkie and contacted the KNLA for help, so a KNLA unit went and met them at L--- and escorted them the rest of the way. Along the path the KNLA soldiers had to remove several SPDC landmines. These photos show the villagers on the way back, with KNLA soldiers guarding alongside the path. [Photos: KHRG researcher] Photos #10-59, 10-60: Villagers from K--- village in Lu Thaw township, Papun district, on the run in January 2004 because of intense activity by SPDC Light Infantry Division #55 in their area. They were already displaced in the forest, but on January 6 th an SPDC column approached their hiding site and they had to flee again; that night was very cold and they had to huddle in the forest with no protection but blankets ( photo 10-59 ). Photo 10-60 was taken 11 days later on January 17 th , after they had been forced to move yet again to a new hiding place. [Photos: KHRG researcher]

Photo #10-61: Naw K---, age 95 (left), and Naw L---, age 80 (right), are both from K--- village in Lu Thaw township, Papun district. They cannot walk well anymore, so the villagers left them hidden in the ricefields before fleeing themselves higher into the forests in January 2004. Left alone like this, the two women say they have trouble cooking for themselves. This photo shows them in their hiding place on January 17 th 2004. [Photo: KHRG researcher]

Photos #10-62, 10-63, 10-64, 10-65, 10-66, 10-67, 10-68: In January 2004, the SPDC launched a full military offensive in southern Karenni (Kayah) State, using the informal ceasefire with the KNU as protection for their southern flank so they could attack forces of the KNPP (Karenni National Progressive Party) and forcibly relocate Karenni civilians into SPDC-controlled sites. SPDC LID #55 was moved in to the area along the recently completed Toungoo to Mawchi vehicle road which passes through Toungoo District. The offensive spilled over into Toungoo and Papun Districts of Karen State after the SPDC soldiers pursued Karenni villagers who sought to avoid internment in relocation sites by fleeing into northern Karen State. As SPDC units swept through the area, many Karen villagers also fled their villages. In photo 10-62 , a group of Karenni villagers arrives at H--- in northern Papun district on January 5 th 2004 after having fled their village at Y--- in southern Karenni (Kayah) State due to SPDC military activity. The remaining photos show some of the group 3 days later, camped out in the forest of Papun district. So far from their home village and fields and in a region new to them, they said they had no idea where they would find food or which way to flee should SPDC troops come near. [Photos: KHRG researchers]

Photo #10-69: Karenni children on the run from SPDC Light Infantry Division #55 in the forest of northern Papun district on January 9 th 2004. [Photo: KHRG researcher] Photos #10-70, 10-71: Karenni villagers who fled SPDC militarisation in southern Kayah State into the forests of Toungoo district in Karen State in January 2004. [Photos: KHRG researcher]

Photos #10-72, 10-73, 10-74, 10-75: Villagers in Lu Thaw township, Papun district, on the run to stay beyond the control of SPDC Light Infantry Division #55. In photo 10-72 , people from L--- village take a rest while heading further into the hills on January 5 th 2004. Photo 10-73 shows people from K--- village on the move on January 5 th 2004, and photo 10-74 shows people of T--- village fleeing the next day. [Photos: KHRG researcher]

Photo #9-9: Children displaced from K--- village in Toungoo District in January 2004 display simple toys they have made from surgical gloves given to them by a Karen mobile medical team. Villagers displaced in the forests struggle not only for survival, but for a continuation of dignity and community, and they see education and play as crucial elements in this struggle. [Photo: KHRG researcher]

Photo #10-76: A family from T--- village in northern Papun district staying in their hillfield hut on December 24 th 2003, in the hope that they will not be found there by SPDC Light Infantry Division #55. [Photo: KHRG researcher]

Photos #6-138, 6-139: This villager from M--- village in Bu Tho township of Papun District, shown here making thatch to repair her roof, was ordered to perform forced labour for the SPDC on the Papun – Pah Heh vehicle road. The road is only used for military control of the area, and the work that the SPDC was expecting the villagers to perform would have taken at least one month to complete; time which the villagers needed for their own work. The villagers therefore did not go when summoned, so they must now live in fear and flee their village whenever an SPDC patrol nears for fear of being arrested. Photo 6-139 shows a section of the road that they were ordered to work on. This road, built by forced labour, runs north out of Papun through the Kaw Pu (Kaw Boke) Army camp to the Pah Heh Army camp (see map ). These photos were taken in December 2003. [Photos: KHRG researcher]

Photo #10-77: Village secretary Saw P---, 32, from B--- village in Than Daung township, Toungoo district, was a leader in his SPDC-controlled village until troops from LIB #509 (Battalion Commander Nyunt Win commanding) looted his belongings, shot and killed his poultry and detained him arbitrarily in December 2003. After that he fled into the forest, where this picture shows him over a month later. [Photo: KHRG researcher]

Photos #10-78, 10-79: After H--- village in Bu Tho township, Papun district, came under SPDC military control and had to begin complying with forced labour demands, young and old fled the village to escape. The 85-year-old man in photo 10-78 said despite his age he didn't want to face the Army's demands. These photos were taken in November 2003. [Photos: KHRG researcher]

Photos #10-80, 10-81: In early November 2003, a combined column of SPDC LIB #341 and IB #35 came to B--- village in Bu Tho township, Papun District. The villagers fled to avoid forced labour and arbitrary detention, and hid in the forest ( photo 10-80 ) until the troops withdrew days later. On their return they found the message shown in photo 10-81 written on their school blackboard by an IB #35 officer: "[We] Want to hold hands in unity. Karen and Burmese are not enemies. The situation is that [we] have arrived. Female teachers and male teachers, whenever the Army comes, Karen nationals themselves must develop the Karen region. [It] Can't be gained by bearing arms and fighting. Officer G--- [signature] IB #35." Ironically, as he wrote this messaage on the blackboard, his soldiers were slaughtering and eating all the livestock left behind by the villagers and looting their houses (see photo 7-79 in Section 7 ). No consultation is ever held with 'Karen nationals' on how to 'develop the Karen region'; instead, the Army simply issues orders for forced labour. [Photo: KHRG researcher]

Photos #10-82, 10-83: In photo 10-82 , villagers in H--- village, Bu Tho township, Papun district prepare their belongings before fleeing into the forest as a group on hearing that an SPDC Army column is approaching the area of their village. Later that day, photo 10-83 shows a woman from the village walking her baby at their forest hiding site, where they will remain until the column moves on. These photos were taken in November 2003. [Photos: KHRG researcher]

Photos #6-23, 6-24: Village men leaving M--- village in Dweh Loh township, Papun district in October 2003 to avoid being taken as porters. They had heard that a column from SPDC IB #57 was on the way to the village. In this district, such columns normally round up any village men they can catch and take them as porters, so these men will not return to the village until certain that the soldiers have left. [Photos: KHRG researcher]

Photo #10-84: This photo taken on September 13 th 2003 shows an abandoned house in Khaw Klah village, Dweh Loh township, Papun district. A month earlier on August 9 th , SPDC soldiers from LIB #434 (Battalion Commander San Aung commanding) came to the village at 10 p.m. and took away the village head and several villagers. Some were reportedly executed, and the rest were still being detained without charge in Papun town when this photo was taken. Their families were given no access to them. Most of the other villagers fled to other villages, leaving only four of the village's 17 houses still occupied. The women in those four houses were waiting to discover the fate of their detained husbands, and then they planned to flee as well. [Photo: KHRG researcher]

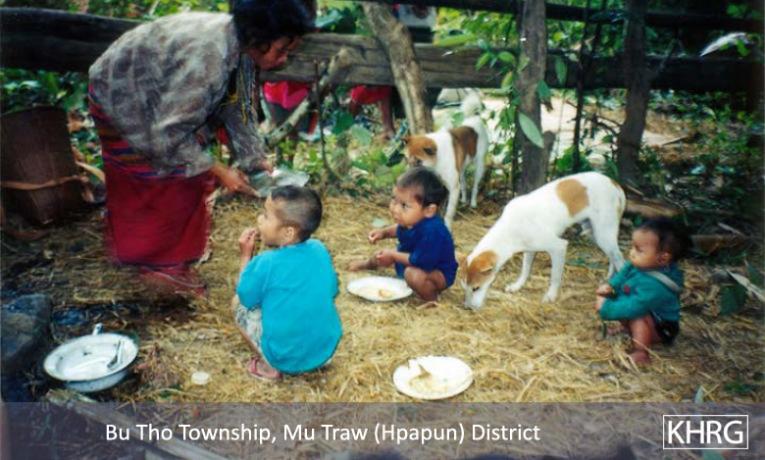

Photos #10-85, 10-86, 10-87: Villagers on the move in T'Nay Hsah township, Pa'an district, in September 2003. They are among a group of 180 people in 30 families who fled villages in T'Nay Hsah township after SPDC LIB #706 Column 2 (Major Kyaw Thu Ra Win commanding) and DKBA units from Brigades 333, 555 and 999 came to establish four new camps at Po Thwee Kyo, Wah Mi Kyo, Thay Daw Kyu Htoo and Tee Wah Klay beginning in July 2003. Villagers from ten villages in the area were forced to use their elephants to haul logs, build the camps, and carry ammunition and supplies to the troops, who also began looting livestock from the villages. Worst of all according to the villagers, they laid landmines which killed over 20 of the villagers' cattle and buffaloes and made the villagers afraid to walk to their fields or in the forest. Most of them therefore fled into the mountains or toward the Thai border. In photo 10-87 , an internally displaced mother and her children share a pot of rice porridge in an attempt to make their rice supply last as long as possible. [Photos: KHRG researcher] Photo #5-13: At 10 p.m. on August 9 th 2003, soldiers from SPDC LIB #434 (Battalion Commander San Aung commanding) captured a number of internally displaced villagers from K--- village in Dweh Loh township, Papun District. They accused the villagers of being KNU sympathisers and then executed some of them. This photo shows the widows of three of the men executed: from left to right, 24 year old Naw B--- who is eight months pregnant, Naw M---, 32, also heavily pregnant, and 23 year old Naw E---. Along with being displaced, they now have to provide for their children alone. This photo was taken in September 2003. [Photo: KHRG researcher]

Photos # 8-3, 8-4, 8-5: These women and their children from K--- village in Dweh Loh township, Papun district fled their villages in July 2003 after being beaten by SPDC officers. When LIB #598 troops came to their village, deputy battalion commander Thein Zaw punched Naw P--- ( photo 8-3 ) in the head and slapped Naw C--- ( photo 8-4 ) in the face. He hit Naw M--- ( photo 8-5 ) on the head with a piece of wood, then kicked her in the head after she fell. These photos were taken in the forest, where they had fled with their children. [Photos: KHRG researcher]

Photos #10-88, 10-89, 10-90, 10-91, 10-92, 10-93: To strengthen military control in Toungoo district and southern Karenni (Kayah) State, the SPDC has been rebuilding the Toungoo-Mawchi road and establishing Army camps along its route. In mid-2003, part of SPDC IB #124 (Battalion Commander Myo Thant Kyaw commanding) established their base at Wa Soe, along this road near the Karen/Karenni border, causing these villagers from Sho Ser village to flee into the hills. Photos 10-90 through 10-92 show them when they first went into hiding in June 2003. Seven months later in January 2004 they were still there, living in simple huts like the one shown in photo 10-93 . See also photos 10-94 to 10-98 . [Photos: KHRG researcher; the dates printed on the photos are wrong.] Photos #10-94, 10-95, 10-96, 10-97, 10-98: Villagers from Wa Soe, located along the Toungoo-Mawchi road, headed into the hills with whatever belongings they could carry when SPDC IB #124 established a camp at their village in June 2003 (see photos 10-88 through 10-93 ). In the forest, they built small hidden shelters like those shown in photos 10-96 through 10-98 . [Photos: KHRG researcher; the dates printed on the photos are wrong.]

Photo #10-99: People in H--- village, Bu Tho township, Papun district, preparing to flee in June 2003 after SPDC troops came and shot and killed one of their fellow villagers just outside the village. The SPDC column had also destroyed some of their rice storehouses hidden near the village, so they did not dare stay any longer. [Photo: KHRG researcher]

Photos #5-20, 5-21, 5-22: Saw Pa La Day, 50, from T--- village in Bu Tho township of Papun District was shot dead on sight by soldiers from SPDC Light Infantry Division #66 on May 30, 2003. His wife, Naw T--- ( Photo 5-22 , which has been damaged), must now raise their three young children alone. The SPDC has been trying to depopulate the hills of Bu Tho township since 1997 by burning villages and shooting villagers on sight. These photos were taken in June 2003. [Photos: KHRG researcher]

Photo #10-100: These villagers from P--- village, Bu Tho township, Papun district decided to leave in April 2003 and build a hut in the hills because the SPDC troops in their area always forced them to porter and stole their livestock. Here they are stopping on their way to eat some rice they brought along. [Photo: KHRG researcher]

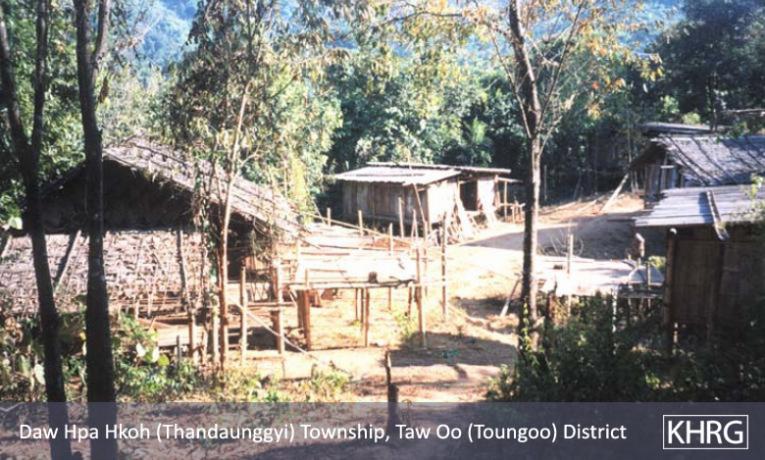

Photo #10-101: This IDP hiding site in northern Papun district was established years ago by people from several destroyed villages, and has now become a well-established site. This photo was taken in April 2003. [Photo: KHRG researcher]

Photo #10-102: Naw M---, 21, is from B--- village in Dweh Loh township, Papun district, which is close to a camp of SPDC LIB #434. Whenever there is fighting in the area, LIB #434 either shells the village with mortars or comes to arrest villagers, so they often have to flee at night. Naw M--- herself is married to a KNLA soldier, and this picture shows her climbing a mountain at night in April 2003 after SPDC soldiers tried to arrest her because there had been fighting not far from the village. If they had captured her they probably would have detained her and her child under threat of death until her husband surrendered. [Photo: KHRG researcher] Photo #2-20: At 11 p.m. on March 27 th 2003, a bomb exploded in the vehicle garage at the camp of SPDC LIB #434 in Bu Tho township, Papun district, destroying the garage and two vehicles. The Battalion responded by shelling the nearby villages without warning. Most of the women, children and elderly villagers ran into the bunkers they have dug beneath their houses for use in situations like these. Adolescent and adult men, however, were afraid to be caught in the village by SPDC troops and accused of planting the bomb, so most of them fled into the forest, including this group from S--- village. This photo was taken on April 2 nd 2003, when the men were still afraid to return to their village. The women must therefore care for the children and elderly in the village and possibly also send food to the men in hiding. If troops come to the village, they must face them even though they may be accused as 'wives of rebels' because their men are missing. [Photo: KHRG researcher]

Photos #5-26, 5-27: Saw M---, 23 years old from P--- village in Bu Tho township, Papun District was shot by SPDC Army soldiers from LIB #38 while in his farmfield hut near his village on March 12 th 2003. The bullet passed straight through his upper arm. He was lucky to escape with his life. After he fled into the forest the soldiers stole 30,000 Kyat, three silver coins, and a bag from his hut. Photo 5-27 shows the cotton swabbing that was packed into the wound being removed by a medic. [Photos: KHRG researcher]

Photo #10-103: An IDP hiding site in Saw Mu Plaw village tract, Lu Thaw township, Papun district in February 2003. There are 12 villages in this tract, but the SPDC destroyed all of them in 1997 and since then the villagers have had to live in hiding in sites like this, regularly moving when SPDC Army units are around. [Photo: KHRG researcher]

Photo #4-14: 35-year-old Naw E--- from P--- village in Ler Doh township of Nyaunglebin District was arrested, interrogated and beaten by soldiers from SPDC IB #60 because her husband works with the KNU. She is shown here with her three children, who had to flee with her in order to avoid further repercussions. This photo was taken in February 2003. [Photo: KHRG researcher]

Photo #10-104: Naw B---, age 75, left her village in Bu Tho township, Papun district and was living upriver from her village when this photo was taken in February 2003. She said SPDC soldiers were based 2 hours' walk from her village, and that despite her age and her blindness she feared they would arrest or abuse her. [Photo: KHRG researcher] Photo #10-105: The family of Naw P--- (right) hides in the forest of T'Nay Hsah township, Pa'an district, in February 2003. DKBA #999 Brigade had become active around their village, and they didn't dare stay and face the forced labour and other abuses. [Photo: KHRG researcher] Photo #10-106: This family in Bilin township, Thaton district, was accused by an SPDC officer of having contact with the KNLA, so ever since they have had to live poorly outside of their home village to avoid arrest. This photo was taken in January 2003. [Photo: KHRG researcher]

Photos # 10-107, 10-108, 10-109, 10-110, 10-111, 10-112, 10-113: On January 15 th 2003 SPDC troops from LIB #434 passed through villages in Bwa Der village tract of Bu Tho township, Papun district, on their way to replace another unit posted along the banks of the Salween River. In each village they passed they tried to catch men as porters and looted the villagers' belongings, causing these villagers from Kyi Thi Pu, Tee Doh Kwee Hta, Klaw Ko, Hsaw Weh, Bwa Der, Noh Kee and Th'Ree Hta villages to flee into the forest. They had been in the forest three days when these photos were taken. [Photos: KHRG researcher]

Photo #9-12: On January 15 th 2003 SPDC troops from LIB #434 passed through villages in Bwa Der village tract of Bu Tho township, Papun district on their way to a post on the Salween River (see also photos 10-107 through 10-113 ), causing villagers throughout the area to flee into the forest to avoid capture. These two children from N--- village were among those who became internally displaced persons when they fled with their families. [Photo: KHRG researcher] Photo #9-13: These children from G--- village in Papun District were forced to flee with their parents when SPDC Army soldiers entered their village early in 2003. They were still living in the forest when this photo was taken in February 2003. [Photo: KHRG researcher] Photo #10-114: Women villagers in Lu Thaw township, Papun district, head along the Pwoh Loh river in January 2003 to distance themselves from SPDC troops who had become active in their area. [Photo: KHRG researcher] Photo #9-14: An internally displaced child returning to his IDP site in Than Daung township in Toungoo District with water that he had just collected from a nearby stream in November 2002. IDPs must exercise extreme caution when doing this as the SPDC has been known to plant landmines on the paths that they know civilians use when going to buy food, collect water, or when going to their plantations. The area to the east of the Day Loh River, where this photo was taken, is known to suffer heavily from landmine contamination. [Photo: KHRG researcher]

Photo # 11-44: Some internally displaced villagers living in the forests of Karen State either learn to make, or are more likely given, locally-made pipe mines from KNLA soldiers and use them to protect their IDP hiding sites. These are typically constructed from lengths of blue plastic plumbing pipe or bamboo packed with gunpowder, metal fragments, and dry cell alkaline batteries to charge a small simple detonator. The sound of an explosion can give IDPs advanced warning of an approaching SPDC Army column, while also slowing that column's approach. The use of mines, however, often backfires. Saw W---, a villager from Lu Thaw township in Papun District, was injured while laying one such landmine. This photo was taken in November 2002, when he was receiving treatment at a KNU clinic. [Photo: KHRG researcher]

Photo #9-15: When this photo was taken in late 2002, Naw S---'s family had already been living a mobile life playing 'cat and mouse' with SPDC forces for several years. Her home in T--- village, Lu Thaw township, Papun district is no longer safe, and the other villagers can provide no more than sporadic education for the children. [Photo: KHRG researcher]

Photos #5-45, 5-46, 5-47: On October 19 th 2002, soldiers from LIB #1 Column 2 (Battalion Commander Myo Myint commanding) saw 35 year old villager Saw Khin Maung Myint along the vehicle road and shot him dead on sight. He lived with his wife and two children in D--- village, Bu Tho township, Papun District. Photo 5-45 shows his final resting place where his friends came to bury him beside the car road a couple of days after his death. Photo 5-46 is of his wife, Naw D---, who is too heavily pregnant to be able to work in their hill field to provide food for her children. Instead, her younger brother Pa G--- shown in Photo 5-47 now has to provide for the family, though he is only 12 years old. [Photos: KHRG researcher]

Photo #10-115: Internally displaced villagers from Thaw Ngeh Der village in Ler Doh (Kyauk Kyi) township of Nyaunglebin District. As a part of the SPDC's ongoing campaign to depopulate the hills of Nyaunglebin District, on October 5 th 2002 soldiers from LIB #175 entered their village and burned it to the ground, while all the villagers fled into the forest. This is not the first time that this had happened; three and a half years earlier in May 1999, a column of soldiers from IB #48 and IB #26 had done the exact same thing, burning the village and all food supplies to the ground. Theirs was only one of a dozen such villages that were destroyed. Over the past twenty years many villagers in Karen regions have gone through repeated cycles of village destruction by SPDC forces, life displaced in the forests, and gradual re-establishment of their villages only to have them burned again. This photo was taken three days after the attack on their village, when the people were returning to the village to rebuild their homes. See also photos 10-116 and 10-117 . [Photo: KHRG researcher] Photos #10-116, 10-117: Children in Kyauk Kyi (Ler Doh) township, Nyaunglebin district, move through the forest with their families in October 2002 after SPDC units burned their farmfield huts and came to their villages. These children from Dta Kaw Der village were fleeing through the forest on October 9 th 2002 after SPDC troops had destroyed their village. See also photo 10-115 . [Photos: KHRG researcher]

Photo #10-118: This villager from T--- village in Than Daung township, Toungoo District has just received word of an advancing SPDC Army column heading in her direction, so she is gathering what few possessions she can carry as she prepares to flee into the forest. Her village to the east of the Day Loh River is labelled by the SPDC a Ywa Bone ('hiding') village, meaning it is not under direct SPDC control. If Ywa Bone villagers are seen by SPDC soldiers they can be arrested, tortured, and killed without any reason. This photo was taken in November 2002. [Photo: KHRG researcher] Photos #10-119, 10-120, 10-121: Villagers in Than Daung township, Toungoo district, building shelters in the forest in late 2002. Their villages were first destroyed by SPDC troops in 1997; they later returned to their villages, but in 2002 SPDC troops targetted them again and they had to move back into the forests. [Photos: KHRG researcher]

Photo #10-122: Karenni villager Saw R---, 41, and his children are from Baw Gho Der township in southern Karenni (Kayah) State but he says they have fled to northern Karen State several times over the years. When this photo was taken in late 2002, he said the SPDC had ordered his village to move to Mawchi town, but the villagers didn't trust them so they didn't obey. He told a KHRG researcher, "We have suffered a lot from SPDC persecution. They eat and burn our paddy, rice, food and poultry. They have killed some of us. We have to flee them and hide in the forest." [Photo: KHRG researcher; disregard the incorrect date stamped on the photo.] Photos #10-123, 10-124, 10-125, 10-126, 10-127, 10-128: Naw K--- (photos 10-123 through 10-126 ) transports her whole family and some of their belongings across the Thi Roh river in Papun district in August 2002. Two weeks earlier, SPDC soldiers from Light Infantry Division #44, Military Operations Command #2, LIB #9, had come to her village led by deputy battalion commander Myo Myint. They stayed in the village only a day, but threatened the villagers and told them, "After we leave, another unit will come." The villagers didn't wait to see, they left for the hills. Naw K--- had to do everything herself because her husband was not at home. The women from her village shown in photo 10-128 said that several of them had done the same; families were divided in the hurry to leave the village. [Photos: KHRG researcher]

Photos #5-61, 5-62: Fifty-five year old Saw T--- had to flee his village in Lu Thaw township, Papun District and live at an IDP hiding place in the hills because of SPDC campaigns to depopulate villages. On July 2 nd 2002, he and his 19 year old son Saw P--- were returning from visiting Saw P---'s grandmother at T---. When they were crossing the Pwa Ghaw – Saw Hta military access road (see map ) near the already destroyed village of S---, SPDC soldiers saw them and immediately shot at them with small arms and mortars. Saw T--- received numerous wounds to his head and legs as shown in the photos. His son was not as seriously injured and was able to go for help, returning later with villagers who carried Saw T--- to safety. Saw T--- told KHRG, "I am only a villager. I do not work against them [the SPDC], but they shot at my son and I. We were both injured. My son wasn't hurt so badly, so he went to get people to carry me." This photo was taken in early August 2002. [Photos: KHRG researcher]

Photo #9-16: Unable to continue enduring the conditions experienced in their villages any longer, many villagers adopt a life of uncertainty, living as internally displaced persons (IDPs) hiding in the forests. These children were photographed in July 2002 in their hidden IDP site in Lu Thaw township, Papun District. [Photo: KHRG researcher; disregard the date printed on the photo.] Photos #10-129, 10-130: Internally displaced villagers in Dooplaya District in mid-2002. The people in photo 10-129 fled after LIB #317 burned their village in Kya In township on April 17 th 2002. Those in photo 10-130 fled after LIB #83 had come to their village in February 2002 and ordered their village to move, taken some villagers as forced labour and killed others. [Photos: KHRG researcher]

Photo #5-74: Saw M---, age 57, says he has been internally displaced and on the run from SPDC troops for over ten years in the hills of Toungoo District near his home village of M---. During that time he has been shot at by SPDC troops several times. In 1995 he was fleeing from IB #26 when he was shot in his left hand. In 2002 he was shot at again, this time by soldiers from IB #92, but was lucky to avoid injury. This photo was taken in April 2003. [Photo: KHRG researcher] Photo #5-76: Naw G---, 70 years old, from K--- village in Toungoo District, lost her 25 year old son Saw Po Htoh in June 1999 when he was shot dead by soldiers from SPDC LIB #439. Living alone as an internally displaced villager in the forests of Toungoo District, she must struggle daily to find enough food to eat. This photo was taken in June 2004. [Photo: KHRG researcher]

Photos #10-131, 10-132, 10-133: These pictures show some some of the remote mountainous forests in the headwaters of the Bilin and Yunzalin rivers where villagers in Lu Thaw township of Papun district have fled to set up hidden shelters since 1997. [Photos: KHRG researcher; disregard the incorrect dates stamped on the photos.]

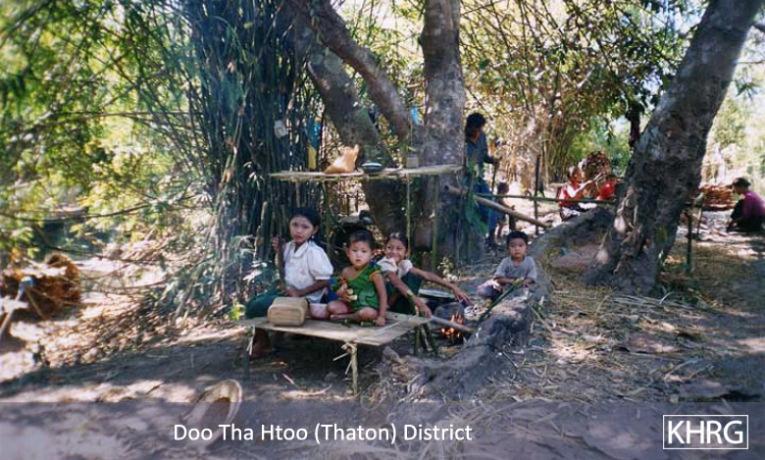

Photos # 10-134, 10-135, 10-136, 10-137, 10-138 These villagers in Thaton township of Thaton district left their villages to escape excessive demands for forced labour, money and goods from SPDC and DKBA forces in their area, and now live in the forest where these photos were taken in February 2005. To survive they make and sell roofing thatch. The girl in photo 10-135 has just set down a large basket used to gather leaves for thatch-making. The woman in photo 10-134 is shaving bamboo to make sticks for frames and ties to weave the shingles together, which is being done by the woman in photo 10-136. In most of the photos, piles of leaves and completed thatch shingles can be seen surrounding the villagers. Each day they must make hundreds of these shingles just to make enough to buy daily rice. It is also a dangerous living; if found living here in the forest by an SPDC or DKBA patrol, they would be rounded up and taken to an Army camp for an indefinite time doing forced labour. Photos # 1-5, 1-6 When LIB #589 came into the Yah Aw area of Shwegyin township and burned Klaw Lu village (see photos 1-1 through 1-3), everyone in Klaw Lu, K’Hee Day and Khaw Hta villages fled into the forest. Two days later on November 20th 2004, these photos show some of them after returning to their villages to retrieve some of their rice supplies so they can survive in the forest.

[Photos: KHRG researcher]

Photos #1-17, 1-18, 1-19: On November 22 nd 2004, villagers from K'Hee Day returned by night to retrieve some of the paddy they had harvested but not stored properly yet when they fled on November 18. Going back by day would be too dangerous because SPDC troops were still in their village, but they managed to retrieve and winnow this paddy from their field huts and take it back to their shelters in the forest. Large quantities of paddy still remained in the field huts, however, more than the villagers could retrieve. [Photos: KHRG researcher] Photo #1-22: On November 23 rd 2004, villagers from L---, in the same area of Shwegyin township as the villages already burned, hurry to harvest as much paddy as they can. They were afraid that the LIB #589 column would come to destroy their village and fields any day. Even so their children remained in school, only coming into the fields to help with the harvest after school ended each day. [Photos: KHRG researcher] Photos # 1-28, 1-29, 1-30, 1-31, 1-32: Photos 1-28 and 1-29 show villagers from Doo Pa Leh and Tee Blah villages, Shwegyin township, Nyaunglebin district, in hiding in the forest after their villages were burned by SPDC troops in late November 2004. After burning the villages the column remained in the area, so people could not return home. The column came just at harvest time, preventing villagers from completing their harvest. Photos 1-30 through 1-32 show a group of villagers who sneaked back to their fields in December to harvest what they could while SPDC troops were not around. Some of the crop had already been destroyed by wild pigs, deer, birds and squirrels. [Photos: KHRG researcher]