SPDC forces do not draw a line between children and adults when they commit human rights abuses. Children living within Karen regions of Burma are frequently the victims of forced labour, detention, torture, shootings, forced relocation, village destruction, displacement, landmines and all other forms of human rights violations documented throughout this photo set. They are deeply and sometimes permanently affected by abuses committed against them as individuals, against other members of their family or the family as a whole, and against their village community.

In the struggle between the Burmese state, determined to militarise and control the lives of the population, and the civilians evading and resisting this domination, children are not bystanders. On the state side, they are forcibly recruited to form a large part of the SPDC Army, while on the civilian side, they are active participants in the survival, evasion and resistance of their families, while some of them become soldiers in resistance groups. Recognising this, SPDC forces do not draw a line between children and adults when they commit human rights abuses. Children living within Karen regions of Burma are frequently the victims of forced labour, detention, torture, shootings, forced relocation, village destruction, displacement, landmines and all other forms of human rights violations documented throughout this photo set. They are deeply and sometimes permanently affected by abuses committed against them as individuals, against other members of their family or the family as a whole, and against their village community.

Many of these human rights abuses tend to affect children more than they do adults, because of children's greater physical and emotional vulnerability and the smaller degree of control that they are able to exert over their own lives. Their health is much more likely than that of adults to fail under harsh conditions; their education can easily be disrupted with lasting effects; and their dependency on other family members makes them more vulnerable to abuses on others. Whether living in SPDC-controlled areas where they are subject to forced labour and the systematic repression and impoverishment of their families, or displaced in the hills where they face malnutrition, disease, landmines and the possibility of being shot on sight, their development as children is often cut off, and they are forced at a very early age to take on full adult responsibilities and more.

The photos below have been divided into seven sections: Violence Against Children (9.1) , Children and Forced Labour (9.2) , Children and Internal Displacement (9.3) , Orphans (9.4) , Health (9.5) , Education (9.6) , and Child Soldiers (9.7) . Additional information regarding the situation of children can be found in KHRG reports on individual regions. For the purposes of this report, 'children' are considered to be all people under 18 years of age.

9.1 Violence Against Children

SPDC commanders do not appear to have a policy of singling out children for violence. However, as part of the civilian population children are generally treated the same as adults, as potential or real 'enemies of the state' to be brought under direct and complete control. If villagers are being detained, therefore, children are detained along with adults (see photo 8-13 ), and if an SPDC column is shooting villagers on sight, they show no hesitation in shooting children (see photos 5-33 to 5-40 , 9-1 to 9-2 , and 5-67 to 5-72 ). In many shooting incidents documented by KHRG, it is clear that the soldiers were more than close enough to know for certain that they were firing on children. Landmines, by their nature as indiscriminate killers, also maim and kill many children in Karen regions (see photos 11-19 and 11-32 to 11-36 ). The use of children for forced labour and their enlarged role in supporting the family due to military oppression (see Sections 9.2, Children and Forced Labour , and 9.3, Children and Internal Displacement , below) increase their vulnerability to military abuse, shooting, and landmines. It is worth noting that the children in photos 11-25 to 11-26 and 11-50 were wounded by landmines when they were trying to find food for their families, while the girls in photos 11-37 to 11-39 were wounded by a claymore mine while doing forced labour as porters. For these and the many other children wounded indiscriminately by military abuses, their wounds will last a lifetime (see photos 9-1 to 9-2 ).

9.2 Children and Forced Labour

Forced labour is usually demanded from villages by quota, either a certain number of people per village, or one person per household. If for example 10 people are demanded from a village of 30 houses, then the village head chooses 10 families which must each send a person, and the next time a different 10 families will take their turn. If the demand is for one person per house, then each family must send someone without exception. Either way, when a demand comes, the family must either send a person or hire someone else to go in their place. Multiple and overlapping demands for forced labour and materials compete with the work which needs to be done in the fields or elsewhere for family survival, forcing families to divide the work among themselves. At busy times in the farming cycle or their other livelihoods, adults take on the work for family survival, while the 'less important' forced labour often falls to the children. This is particularly true when forced labour requires a large number of villagers, like road labour, preparing and delivering large quantities of thatch, or portering; for short-term labour where the family's turn seldom comes (like set tha messenger labour), children are involved less often. Some people would chastise parents for subjecting their children to forced labour in this way, but in their view the child is dependent on the family, so family survival must come first. The fault here lies not with the parents, but with those who demand forced labour.

When adults go for forced labour, they often have no choice but to take their infant and toddler children along with them. Similarly, in Karen villages children as young as 6 or 7 are already caring for their younger siblings, so when these older children go for forced labour their baby or toddler siblings often accompany them, and even take part in the work; this is why children as young as 4 or 5 can be seen hauling or breaking rocks for road work in photos 6-115 to 6-118 .

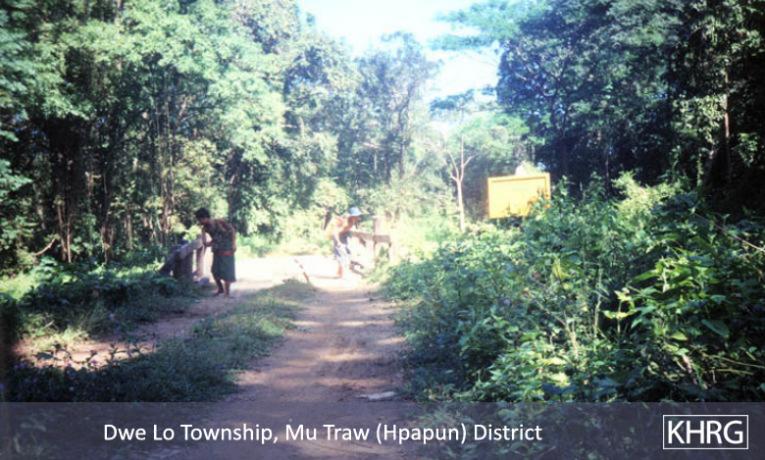

When large numbers of forced labourers are demanded, so many children are involved that village schools often close down. For example, when villagers in Thaton district had to gather stone for over two months from April to June 2004 to build a road for the SPDC, children often formed over half the workforce, especially because this work occurred when ricefields had to be prepared, ploughed and planted (see photos 6-115 to 6-118 and 6-119 to 6-122 ). Children are regularly involved in forced labour clearing the scrub along roadsides (see photos 6-25 to 6-34 , 6-168 to 6-171 , and 9-7 ), preparing and delivering thatch to SPDC and DKBA camps (see photos 6-227 , 6-228 to 6-236 , and 6-248 to 6-250 ), and even girls as young as 11 are forced to do the difficult and dangerous work of portering Army supplies (see photos 9-6 and 6-44 to 6-46 ).

In most cases the children must do the same work as the adults, though if small they may get a smaller load or slightly less gruelling job. They sometimes have to sleep in the open at the worksite (see photo 6-152 ), exposing them to malaria. Portering and road work also exposes children to landmines. The girls in photos 11-37 to 11-39 were among a group of villagers forced to porter supplies along a road the SPDC suspected was mined, and ended up badly wounded when one of the group triggered a tripwired KNLA claymore mine.

Though much forced labour is done without on-site military supervision, the SPDC is fully aware that children are doing much of the work. The 12 year old girls in photos 9-4 and 9-5 were paid by an SPDC officer for the work they did rebuilding roads in Papun District, so he clearly knew who was doing the labour. Past KHRG interviews and written SPDC order documents have shown that SPDC commanders only object to children doing forced labour if it results in the work not being completed on time.

9.3 Children and Internal Displacement

The greater burdens imposed on families by living under military control force children to take on a much larger role in helping to ensure their family's survival, and this role is magnified even further when the family becomes displaced. On the move, children help carry the food and belongings the family will continue to need, and bigger children sometimes carry their smaller siblings. Adults travelling alone can move more than twice as fast as families with small children, yet unlike the elderly, children are never knowingly left behind. Many of the photos below show the extra effort parents are willing to go to for the sake of their children (see for example photos 10-123 to 10-128 ), even when they know that the whole family may be captured by SPDC soldiers as a result. While living a mobile life in hiding, children's food and shelter needs are always prioritised (see photos 1-13 to 1-16 ) and taken care of by the extended family. Their education suffers, but adults place priority on keeping some form of rudimentary schooling going no matter how difficult the circumstances (see Section 9.6.1, Education for Displaced Children ). At the same time, they become more central to the family's survival by participating in farming and other livelihoods (photos 1-22 and 10-134 to 10-138 ), fishing, and foraging.

All of these activities expose them dangerously to shooting or capture by SPDC patrols (see Section 9.1, Violence Against Children ) and landmines (see photo 9-14 ). Small children easily become malnourished, particularly if their parents fall ill or are killed. Lack of access to medical care makes every illness a threat (see Section 9.5, Health ), and wounds, whether from landmines or jungle thorns, can be fatal due to bleeding or infections. Yet amid all of this they remain children, trying to carry on with play (see photos 10-12 to 10-15 and 9-9 ), school, and family life. Even play can now be dangerous, as it is for the children in photo 9-10 playing in the burned and possibly mined ruins of their destroyed village. Some families try to take their children to Thailand, where they know there are relatives and schools in refugee camps, or even send their children ahead with other families while they try to continue surviving near home. However, even if they reach the border children are not safe against forced repatriation by Thai troops (see photos 10-162 to 10-163 ), or from the difficult and sometimes dangerous life of refugees (see photos 10-182 to 10-194 ).

9.4 Orphans

Every time a villager dies, whether tortured to death by SPDC soldiers, killed by a landmine during forced labour, or killed by illness due to the SPDC blockade on medicines entering the hills, the lives of many people are affected – first and foremost those of his or her children. Compensation is almost never paid in such cases, and insurance is unknown in rural Burma. The surviving parent must find a way to support the children alone, sometimes with the help of other families. Making this more difficult, despite the loss of a parent the family is still considered one household for forced labour purposes, and must therefore still fulfil SPDC forced labour quotas (see Section 9.1, Violence Against Children , above) – meaning the children will now have to do even more forced labour in addition to supporting the family. If no parents are left the orphans fall into the care of the extended family (see photos 9-17 , 9-20 to 9-21 , 5-52 to 5-57 , and 9-25 ). This usually means grandparents, uncles, or aunts, though if the orphans are small this makes survival even harder for elderly couples or families who may already be struggling to survive. The baby in photo 9-22 no longer has any close relatives surviving, and fell into the care of the village community as a whole after SPDC troops beat his father to death.

After losing one or both parents, the elder children become the main providers for their younger siblings and sometimes for the surviving parent. After her father was tortured to death, 13 year old Ma M--- had to leave school to help her mother (see photo 4-13 ). Already three years an orphan, the 12 year old boy in photos 9-18 to 9-19 has become adept at many kinds of labour in order to support his widowed mother and younger siblings. Pa G---, newly orphaned at age 12 ( photo 5-47 ), now faces the same situation. Even more than other children in the villages, the orphans must learn to act as adults very early.

9.5 Health

The burdens of forced labour, extortion and other demands in SPDC-controlled areas, the deliberate undermining of village food security in hill areas which the SPDC is trying to depopulate, and the lack of access to sufficient food and clean water in forced relocation sites, are all leading to widespread malnutrition among children in Karen State, and this in turn makes them more vulnerable to illnesses, infections, and other complications.

Hospitals and medical clinics, however, are inaccessible to most rural children. Care and medicines at town hospitals and village clinics are far too expensive for most people to be able to afford them, partly because corrupt doctors inflate the prices. The local clinics which smaller villages are ordered to build at their own expense usually sit abandoned, because the medics sent from town have disappeared never to be seen again. In SPDC-controlled villages, children therefore receive medical attention either from traditional healers using forest medicines, or sometimes questionable 'injections' and pills prescribed by local medicine sellers.

For children in villages beyond direct SPDC control the situation is worse, because the SPDC blockades medicines and medics from reaching Karen hill regions, and has outlawed even the possession of medicines in many of these areas to prevent medicines reaching IDPs and Karen forces. These blockades do not kill many Karen soldiers, who have their own supply lines, but they are killing many IDPs and hill villagers. The eleven year old boy in photo 9-25 lost both parents to illness because of the SPDC medical blockade. Karen villagers in the hills are forced to rely on traditional forest remedies, animist practices, and traditional healers, which can be helpful but often prove insufficient (see photos 10-3 to 10-4 ). 'Modern' medicines, dressings and treatment are only available from mobile medics (see photos 9-23 and 10-151 to 10-153 ) – sometimes KNLA medics, sometimes travelling medical teams from local IDP assistance organisations – but their presence is sporadic and they themselves are usually short of medicines (see photo 9-24 ), because most international organisations refuse to give aid to Karen groups seen as having 'political connections'. Ironically, these same international organisations do give money and aid to organisations controlled by the SPDC, like the Myanmar Maternal and Child Welfare Association, reflecting the hypocrisy of their claims of 'humanitarian neutrality' and 'apolitical humanitarian aid'.

Attempts by SPDC columns to force villagers out of hill areas have a dire effect on maternal and infant mortality and morbidity. When villagers have to stay on the move to avoid these columns, infants cannot be properly cared for (see photos 8-10 to 8-12 ) and women giving birth must do so in unsanitary conditions with no outside help. Unable to flee when the columns approach, women giving birth or with newborns but sometimes remain behind to face the soldiers alone (see photo 2-30 ). Children with disabilities also have difficulty fleeing with the other villagers, so their parents remain behind with them to face the soldiers (see photo 10-148 ). The lack of sufficient nutritious food resulting from a life on the move and SPDC destruction of rice supplies lead to maternal and infant malnutrition (see photos 8-21 to 8-23 ), and many children die before age five. Those who survive beyond that age must then face the threats of SPDC violence against children and forced labour which were discussed in earlier sections.

9.6 Education

Schools in Karen regions can be divided into state-controlled schools and non-state schools. State-controlled schools exist in most SPDC-controlled villages. They are built by the unpaid labour of villagers and at their expense, but the SPDC sets the curriculum and forbids any language but Burmese being taught. Some of the teachers are sent by the SPDC education department, while others are hired locally. Students must pay fees and provide all their own materials, so many children either cannot attend or drop out early. Non-state schools are outlawed by the SPDC, but they exist in villages remote from direct SPDC control. These are set up by villagers to teach their own children, staffed by rotating local volunteers or low-paid village teachers who receive some support from the villagers. Villages establish these schools because they cannot afford to pay for state-controlled schools; they need the children to help at home and there is no state-controlled school nearby; they do not dare send their children to SPDC-controlled villages due to the risk of forced labour; they do not accept the SPDC school curriculum and want their children to become literate in their own language; or any combination of these reasons. Most of these schools only reach primary level, because the teachers themselves may have had only primary-level education. If the SPDC finds these schools, they are destroyed. Another form of non-state school is established when villagers go into hiding to avoid SPDC abuse, and set up rudimentary schools in IDP hiding places to continue education for their children. In some areas, the KNU has helped to set up middle and high schools which teach a Karen curriculum using Sgaw Karen as the main medium of instruction. Primary school runs from Kindergarten to 4 th Standard (Grade 4); middle school from 5 th to 8 th Standard, and high school from 9 th to 10 th Standard. Post-secondary education is only available at universities and colleges in the cities, or by distance education from the main towns.

Village and IDP schools are discussed below in Section 9.6.1, Education for Displaced Children , and state-controlled schools are discussed in Section 9.6.2, Education in SPDC-controlled Villages .

9.6.1 Education for displaced children

When SPDC forces attempt to clear villagers out of an area, village schools are one of the main targets for destruction – probably because village schools are a symbol of villagers' ability and desire to organise outside the state system, and because they form focal points for community and Karen identity and solidarity. Village schools are therefore burned by SPDC columns (see photos 1-52 to 1-55 and 9-31 ). The villagers, however, carry their commitment to education into their displacement, such that one of the first priorities of displaced villagers is to continue schooling their children. Their motivation for doing this is not material or utilitarian, because in remote rural areas schooling is not seen as a ticket to material success; in Sgaw Karen there is even a saying, "Go to school, eat rice. Don't go to school, eat rice." Yet Karen villagers still see schooling their children as essential to the continuation of their identity, culture, language, and sense of community, which are needed if they are to retain hope in their struggle against state oppression. This is why schooling, though it would not appear immediately essential to survival, is continued by displaced villagers the moment they can stop in one location for more than a day or two. Village teachers, or volunteers with some education themselves, immediately assess the number and ages of children, plan and begin teaching, usually on the ground with a makeshift blackboard (see photos 10-154 to 10-156 , 1-52 to 1-55 , 9-37 , and 9-26 ). The teachers may have no more than primary education themselves, and the students only have whatever notebooks and pencils they managed to bring with them. Yet this provides the entire community with a sense of continuity, dignity, and solidarity despite the difficulties of survival as IDPs (see photos 10-7 to 10-11 , 10-160 to 10-161 , 9-30 , and 9-33 ), and forms a centre of community activity which helps buoy the spirits of everyone (see photos 10-157 to 10-158 ).

Villagers who manage to establish themselves in hiding sites scattered throughout their home area sometimes cooperate to establish a school in some hidden central location for all of their children, and build a semi-permanent structure to house it (see photos 10-160 to 10-161 , 9-35 , and 9-38 ). These schools are plagued by a lack of education materials (see photos 9-27 to 9-28 , 10-157 to 10-158 , and 9-33 ). Photo 9-30 shows one such primary school set up by villagers in Dooplaya District after they fled an SPDC forced relocation site where they were not allowed to have a school. Though the poverty of the displaced children is clear in the photo, their parents are determined to keep them in school. In some areas where teachers are available, villagers have managed to set up middle or high schools with KNU support (see photos 9-27 to 9-28 ). These schools teach a curriculum established by the KNU education department, with Sgaw Karen as the main medium of instruction.

All of these schools, however, are subject to the same situation as the displaced communities themselves; children sometimes cannot participate when they need to support their families (see photo 9-34 ), and the schools are frequently closed or abandoned when SPDC columns enter the area (see photos 9-27 to 9-28 , 9-29 , 10-160 to 10-161 , 9-32 , 9-33 , and 9-36 ). The teacher at the hidden school for displaced villagers shown in photo 9-32 , for example, said that her school can only remain open for an average of one week each month due to the degree of SPDC military activity in the area.

9.6.2 Education in SPDC-controlled villages

Many Karen villages have state-controlled schools. The construction of these is ordered by local SPDC officials without consulting the villagers. If money is provided by the state it is all purloined by the officials, and the villagers are ordered to supply all needed materials and build the school without pay (see photos 9-42 to 9-43 ); sometimes they are even forced to pay additional 'construction fees' to add to the profit of the officials. These orders can be highly erratic, particularly when officials want the school to be an ostentatious showpiece for their own prestige. For example, photos 9-48 to 9-49 show a school which villagers were ordered to build, only to be told when they were half-finished that they must build a more elaborate school on a different site. After the villagers have done all the work and paid all the costs, the schools are proclaimed as 'government' schools set up out of SPDC generosity (see photos 9-39 , 9-41 , and 9-50 ), and plaques are mounted giving credit to Army and SPDC officials (see photos 9-42 to 9-43 ).

Some teachers are sent from towns by the SPDC education department, while others are hired from the local population. The villagers must pay most of the salaries and support the teachers with rice, and students must pay school tuition fees and buy all education materials themselves. Sometimes the teachers sent from town disappear on some pretext and never return. In the past, some of these have been discovered to have paid bribes to town officials to continue paying their salary as if they were still at the village school. The school curriculum is set by the SPDC, including an SPDC version of history which glorifies Burmese kingdoms and the Army and portrays non-Burman ethnic groups as backward and undeserving of political representation. The medium of instruction is Burmese. Karen languages are not taught, and some schools even forbid students from speaking them (see photos 9-51 and 9-52 ). If children want to become literate in their own language, they must do so at home. The purpose of the schools is stated as "Morality, Discipline, Education" – in that order (see photos 9-42 to 9-43 ).

Many children cannot attend these schools because their families cannot pay the tuition fees, or because they are needed to perform their family's quota of SPDC forced labour so their parents can still produce food for the family (see photos 9-40 , 9-44 , and 9-47 ). Teachers, even those sent from town, sometimes flee the village when SPDC authorities are demanding forced labour, causing the school to close down (see photo 10-159 ). Photos 9-45 to 9-46 show the 2003 school closing ceremonies in one village tract of Papun District, held a month early because SPDC columns in the area were capturing people for forced labour. This is not unusual. Even as the ceremony occurred, the children of one village couldn't attend because they were being detained in their village by SPDC troops.

|

"In Commemoration" Bilin Township, Meh Na Tha village tract, K--- village self-help primary education school. This new school was built under the supervision of Light Infantry Division #66 headquarters and Light Infantry Battalion #5. With the cooperation of K--- village this school was finished. 1365 Thadin Kyut full moon Morality, Discipline, Education |

9.7 Child Soldiers

The SPDC, DKBA, and KNLA all recruit boy children to their ranks. In 2002, the Human Rights Watch report 'My Gun Was as Tall as Me': Child Soldiers in Burma estimated there to be 70,000 child soldiers in the SPDC Army, making up twenty percent of all SPDC soldiers, while the DKBA and the KNLA had roughly 500 child soldiers each. None of these armies appear to have taken action to stop child recruitment since then. By any estimate, it is clear that the SPDC is by far the worst offender in recruiting child soldiers, and testimonies show that it is also the worst in its treatment of child soldiers.

Most SPDC soldiers are forcibly conscripted. In central Burma, recruiters are paid incentives for each recruit obtained, and they target children as the easiest recruits. Tricks are used such as threatening boys that they will be sent to prison for failure to possess a National Identity Card if they don't join the Army (see photo 12-9 ). They are then conscripted as 'volunteers', and their age is inscribed as 18 because official Army rules set this as the minimum (see photos 12-7 to 12-8 ). If too young to stand training, they are held for long periods in Su Saun Yay ('gathering place') camps until considered ready (see photo 12-13 ). According to former child soldiers, they are beaten and otherwise abused during their four months of training, and any who try to escape are publicly tortured. Once assigned to active units, child soldiers often have trouble keeping up with older soldiers and are regularly beaten as a result. Officers steal part or all of their salaries (see photo 12-11 ). Some are used for road labour and other non-military work (see photos 12-7 to 12-8 and 12-9 ), while others become errand-boys for officers. They are beaten when they make a mistake (see photo 12-12 ) or when their officers get drunk (see photos 12-4 to 12-6 ). They are also used to round up villagers for forced labour, destroy villages, and take part in combat. Most of them are never allowed any contact with their families, who in most cases never find out what has happened to their son from the moment he disappears from his home (see photos 12-11 and 12-7 to 12-8 ).

Some manage to escape, but even then there are few options open to them. If they try to return home they are usually caught, sent to prison for desertion, then a year later forced back into the Army (see photo 12-3 ). Many end up in the hands of Karen resistance forces, but the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), Unicef, and the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) have consistently refused to help in any way. Only since the beginning of 2005 has UNHCR begun to show some interest in assisting escaped child soldiers who reach Thailand, but they are hampered by an agreement between Thai and SPDC authorities specifying that Thai forces will hand any deserters back across the border to the SPDC. With no other options open to them, many escaped child soldiers end up crossing the border and working illegally in Thailand, or joining resistance armies even if they are still children (see photos 12-11 and 12-12 ).

Many children who join the KNLA and DKBA do so as volunteers, but both groups also do some forced recruitment. Villages are ordered to send a certain number of recruits, and some of those sent are usually children. Rather than sending them home, the armed groups accept them. Photo 12-10 shows one boy who was forcibly recruited to the KNLA in this way, and photo 12-15 shows two boys who were forcibly recruited to the Karen National Defence Organisation (KNDO), a KNLA-affiliated militia.

For further background on these issues, see also Abuse Under Orders: The SPDC and DKBA Armies through the Eyes of their Soldiers (KHRG #2001-01, March 2001).

Photos #9-1, 9-2: Twelve year old Saw S--- from T--- village, Toungoo District, displays a wound that SPDC soldiers inflicted upon him when he was only six. At that time, he and his family were internally displaced, living in a hut in their ricefield. SPDC Army soldiers found the hut, quietly approached it and opened fire. He was struck in the arm as his father attempted to carry him to safety. The bullet shattered the bone in his forearm, rendering his right arm unusable. For villagers living in the forest, any encounter with SPDC forces can be disastrous. Many are simply shot on sight with no questions asked. Photo 9-1 was taken in January 2004, while photo 9-2 was taken seven months later in August 2004. Photo #11-19: Naw K---, age 16, from H--- village in southern Karenni (Kayah) State, was walking her younger siblings across Karenni toward the Thai border so they could attend school in one of the Karenni refugee camps in Thailand in April 2004, but along the way she stepped on a landmine laid by the Karenni Solidarity Organisation (KnSO), a Karenni armed group allied with the SPDC. She was later brought to a KNU clinic in Papun district, where this photo was taken as she was recovering in May 2004. KnSO mines are also involved in photos 11-32 to 11-36 below . [Photos: KHRG]

Photo #8-13: Naw S---, age 29, is from K--- village in Lu Thaw township, Papun district. In January 2004, SPDC troops from IB #60 found her living in hiding in the forest. They arrested her and took her and her three children to their camp at Pwa Ghaw. She was heavily pregnant, but the soldiers gave her and her children no food or rest along the way or when they reached the camp. Village elders of the nearby SPDC-controlled village of Pwa Ghaw managed to have her released and gave her rice, water, and clothing, but she had a miscarriage and almost died. She stayed with the villagers for 7 days, and then they took her back to the place where her husband was staying. Living back in the jungle without medicines, she fell ill and two of her three children got sick and died. She then fled to Thailand with her only remaining child, and arrived in February 2004 at the refugee camp where this photo was taken. The artwork behind her, depicting peaceful village life, was done by children in the refugee camp. Photos #11-25, 11-26: This adolescent boy from Shwegyin town in Nyaunglebin District stepped on a landmine as he was going to collect dogfruit in November 2003, shortly before this photo was taken. [Photos: KHRG]

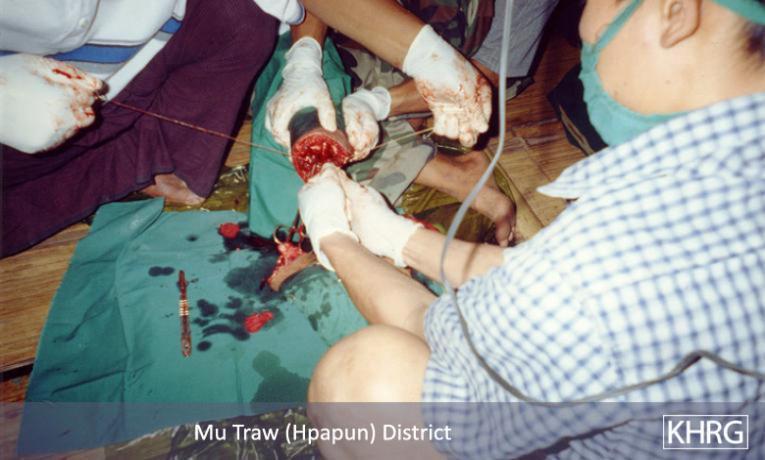

Photos # 11-32, 11-33, 11-34, 11-35, 11-36: On August 11 th 2003 Saw H---, a 17-year-old from B--- village in southern Karenni (Kayah) State, stepped on a landmine planted near his village by SPDC-allied Karenni Solidarity Organisation (KnSO) soldiers commanded by officer Hsa Wah. It was not until two months later that he reached this KNU clinic in Papun District, where this photo was taken. The medics decided his lower leg (shown in photo 11-32 ) could not be saved. The remaining photos show stages of the amputation, which is done with only the simple medical tools available and without general anaesthetic. Many of those who step on landmines die from loss of blood or shock long before they can be either taken to medical care or wait until it reaches them. KnSO mines are also involved in photo 11-19 above . [Photos: KHRG]

Photos# 11-37, 11-38, 11-39: On January 4th 2003, SPDC LIB #341 (Kyaw Mya Thaung commanding) ordered villagers from P--- and K--- villages to carry Army supplies from Hsaw Bweh Der to K’Hee Kyo Army camp in Bu Tho township of Papun District. These girls aged 12, 15, and 20 were part of the group, which had to leave Hsaw Bweh Der at 7 a.m. The soldiers who were supposed to accompany the villagers set out for K’Hee Kyo through the forest, but ordered the villagers to walk along the vehicle road, apparently suspecting that the road may be mined. Shortly before arriving at K’Hee Kyo camp one of the villagers hit a tripwire, detonating a claymore mine placed there by the KNLA. Nine of the villagers were wounded. Photo 11-37 shows Naw A---, age 12, who was hit by shrapnel in the shoulder, left arm, left wrist, and under her breast; medics were later unable to remove the shrapnel, and a month later she said it still made her dizzy often. Beside Naw A--- in photo 11-38 is Naw B---, 15 (left), who was wounded in the bladder; both girls are shown in school uniform. Photo 11-39 shows 20 year old Naw M---, who sustained shrapnel wounds to her left thigh. Four others were injured more seriously and were sent to the SPDC hospital in Papun town. The use of villagers as human minesweepers is a common SPDC tactic throughout all areas of Karen State. [Photos: KHRG researcher]

Photos #5-33, 5-34, 5-35, 5-36, 5-37, 5-38, 5-39, 5-40: On October 30 th 2002, a number of villagers from S--- village in northern Lu Thaw township, Papun District, went to harvest the paddy from their hill field at T---. SPDC forces have been trying to depopulate this hill area since 1997 by destroying villages, crops and food supplies and shooting villagers on sight, but thousands of villagers still survive here. At 3:30 pm as the villagers were collecting their harvest, soldiers from LIB #235 crept up on them and opened fire. One of the villagers, 25 year old Saw Ray Bee Wah, was shot dead, and at least five other villagers were injured in the shooting. Photos 5-33 , 5-34 , and 5-35 show Naw L---, 15, who was shot just below her left elbow. Photos 5-36 and 5-37 are of eight-year-old Naw M---, who was shot in the abdomen, the bullet barely missing her kidney. Photos 5-38 and 5-39 show the gunshot wound in the leg of Saw T---, 38. Fortunately for him, the bullet passed right through his leg without hitting the bone. Photo 5-40 shows Saw T---, 20 years old, who was shot in the forearm, having his wound cleaned by a Karen medic. Medics in the area can do little but clean the wounds due to the lack of medicines and clinic facilities. Saw P---, a 32-year-old villager not shown here, was also wounded. The reason so many people were hit is that they must harvest in open hillside fields with no cover, while SPDC troops can creep up in the forest to the very edge of the field without being detected. In these circumstances there is no doubt that they knew they were firing on civilians and children. These photos were taken in November 2002. [Photos: KHRG]

Photos #5-67, 5-68, 5-69, 5-70, 5-71, 5-72: These photos follow on from photos #D4-D7 in KHRG Photo Set 2002A . After being ordered to relocate along with other villages in Kya In township of Dooplaya district in April 2002, a group of villagers from Tee Law Bler tried to flee to Thailand. On April 28 th 2002 soldiers of SPDC IB #78, Battalion Commander Myo Htun Hlaing commanding, found them sleeping in farmfield huts not far from their village, surrounded the huts and opened fire, killing ten and wounding nine more. Six of those killed were children, four of them under the age of ten. All of those who survived the incident later arrived at Noh Po refugee camp in Thailand. Photo 5-67 shows U K---, 44, with his two surviving children, nine-year-old Saw N--- (left) and twelve-year-old Naw K--- (right). Photos 5-68 and 5-69 show the injuries to Saw N---'s arm from the shooting. The bullet penetrated his upper arm, shattering the bone. Photos 5-70 , 5-71 , and 5-72 show Naw K---'s wounds to her right forearm, and the homemade splint she was using. Their father told KHRG researchers: "We fled before the Burmese [soldiers] arrived. I fled with my wife and children to our field hut. We planned to go to Noh Po [refugee camp] in the morning, but before we could, they came and attacked us in the night time. It was about 10:00 or 12:00 [o'clock] when they attacked us. They shot at my hut and my brother's hut. They continued shooting for about five or six minutes. ... Three people in my family died and two were wounded. My wife was wounded but died 12 days later. Ten days after she was wounded she gave birth [the baby did not survive], but two days she later also died. ... I don't know why they wouldn't allow us to leave [to the refugee camp]. Maybe they thought that we would leave our children in Noh Po and would go back to fight them. I think that they are afraid that other people and other countries would learn about them so they didn't allow us to leave." His wife Naw Pee Lee is shown in photos #D5 and D6 in KHRG Photo Set 2002A . [Photos: KHRG]

Photo # 11-50: 46 year old Saw K--- from N--- village in Than Daung township of Toungoo District lost his son to an SPDC landmine. Major Aung Ko Lin, battalion commander of IB #53, acting under the direct orders of Captain Thet Oo, Operations Commander of Southern Regional Military Command's Strategic Operations Command #3, planted many landmines along the banks of the Klay Loh River in early 2002. Saw K---'s son Saw Si Si Htoo was only 14 when he was killed outright by one of these mines while fishing in the Klay Loh River on April 26 th 2002. [Photo: KHRG]

Photos # 6-115, 6-116, 6-117, 6-118: On April 20 th 2004, Brigadier General Myint Aung, commanding officer of SPDC Military Operations Command #9 based in the Lay Kay Army camp in Bilin township of Thaton District, ordered the reconstruction of sections of the old colonial road running from Kyaik Khaw (Thein Seik in Burmese), to Wee Raw village, before turning north to follow the Donthami River to Lay Kay village (see Thaton district map ). Other sections of the road further north which have not yet been restored will pass through Htee Pa Doh Hta and Yo Klah villages, continuing to follow the Donthami River to the edge of Papun district, where it will turn east to Ka Dtaing Dtee village in Dweh Loh township of Papun District (see Papun district map ). Should this road be fully restored, it will provide a direct link between Thaton and Papun, giving the SPDC the ability to rapidly deploy troops anywhere along the road's length. Similar to what has happened in other road projects, Army camps will be established all along the road, leading to increased militarisation, forced labour, oppression and displacement of civilians throughout the region. According to a KHRG researcher working in the region, "Since the KNU and the SPDC have made the ceasefire [in January 2004], the suffering of the villagers has not reduced. Furthermore, the SPDC and DKBA soldiers have been repairing the car roads, so they have been forcing the villagers like slaves more and more." These photos show villagers from K--- village gathering the 300 piles of stone for the road that they were ordered to provide. Each pile of stone is one kyin – 100 cubic feet, measured as 10 feet (3 m.) square by 1 foot (30 cm.) deep. These villagers began work on the piles of stone on April 20 th 2004, but were still collecting stone two months later in June. Many parents send their children to do the work because the adults are needed in the farmfields or doing other work for family survival; this is why more than half of those in the photos are children. Alternatively, entire families including children come out to do the work in order to get it done faster so time will still be left for their farming and other work. Most of the children shown in these photos are aged between seven and thirteen years old, but even those as young as four or five (see photos 6-115 and 6-116 ) come along because they cannot be left home alone, and end up carrying rocks along with their older siblings. See also photos 6-119 through 6-122 below and photos 6-123 through 6-130 in Section 6 , which show other nearby villages also collecting stone for the same road. These photos were taken in May 2004. [Photos: KHRG]

Photos # 6-119, 6-120, 6-121, 6-122: Villagers from K--- village in Pa'an township of Thaton District performing forced labour for the SPDC on the Kyaik Khaw-Lay Kay car road. All of the villages lying on or close to the path of the road were ordered to collect stone that will later be used in the road's construction. Each village had to assemble 300 kyin of stone – one kyin being 100 cubic feet, measured as 10 feet (3 m.) square by 1 foot (30 cm.) deep – and place these square piles of stone neatly along the road route. According to the KHRG researcher who took these photos, "They [the villagers] have to build roads and bridges, stand sentry on the roads, and collect stones that are used in the road construction. The SPDC soldiers from Military Operation Command #9 commanded by Brigadier General Myint Aung are the ones who are forcing them to do this. They are based at Lay Kay Army camp and are forcing the villagers to collect the stone for the car road. Each village has had to collect 300 piles of stone. The villages west of the road are Maw Lay, Ka T'Daw Ni, P'Nweh Klah, Noh Nya Thu, Lah Ko, Ka Meh, Dta Bpaw, Ler Klaw and Lay Kay villages, while the villages to the east are Ei Heh, Kru Si, Noh Aw La, Pwa Ghaw, Kyaw Kay Kee, Dta Thu Kee, Noh Law Plaw, Noh Ka Day, Htee Pa Doh Kee, Meh Theh Pwoh, and Ha T'Reh villages. The villagers from all of these villages had to collect 300 piles of stone per village. The villagers need to work in the fields during May, but they didn't have time to work for themselves. The DKBA forced them to repair the car road, and the SPDC also forced them to repair the road and collect the stone. The villagers tried to cultivate their fields but the SPDC and the DKBA forced the villagers to do many things so they can't work their fields." Because it was a crucial time in the crop cycle, many of the workers were teenage girls and boys like those in photos 6-119 and 6-120 and younger children whose parents needed to be in the fields. Whenever work needs to be completed quickly or if there are not enough adults who are available to work, the village children must also pitch in and work alongside the adults. Photos 6-115 through 6-118 above and 6-123 through 6-130 in Section 6 portray other villages in the vicinity which were also ordered to work on this road. These photos were taken in May 2004. [Photos: KHRG]

Photo #6-227: Villagers from W--- village in Dweh Loh township of Papun District providing roofing thatch to the SPDC in February 2004. Captain Lu Maung Htat, an officer of Military Operations Command ( Sa Ka Ka ) #9, ordered the villagers to deliver the thatch to the Ku Thu Hta Army camp. Children are involved because the family needs to work efficiently to get all their work done, which includes multiple overlapping demands for forced labour along with their own work. SPDC officers never object to the involvement of children as long as the work gets done. [Photo: KHRG]

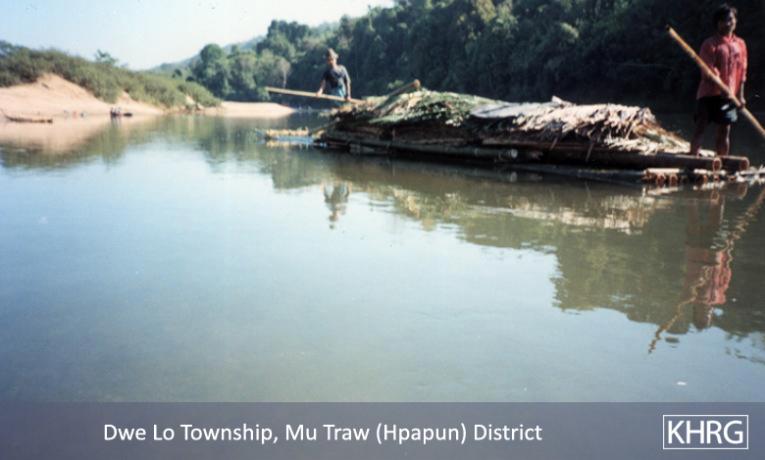

Photos # 6-228, 6-229, 6-230, 6-231, 6-232, 6-233, 6-234, 6-235, 6-236: Throughout January 2004, commander Zaw Lwin Htut of LIB #349 demanded large quantities of bamboo and roofing thatch from numerous villages in Dweh Loh township of Papun District. Each household in all of these villages was ordered to deliver six lengths of bamboo and five shingles of thatch to the Win Maung SPDC Army camp adjacent to the Wah Mu relocation site. Saw S---, 29, from P--- village told a KHRG researcher, " I had to go to send six pieces of bamboo and five shingles of thatch to the SPDC at Wah Mu. They are from LIB #349. The name of their commander is Zaw Lwin Htut. They didn't pay us; they forced us to work. If the people don't work they won't allow them to stay in the village. They said that people who don't go to do loh ah pay , portering, or set tha are not villagers [i.e. that they must be rebels]. If the people don't work they have to hire someone [itinerant labourers], and if they don't hire labourers then they have to leave." The villagers were not paid, nor were they provided with any tools or even food. Providing these materials is labour intensive. Photo 6-228 shows a villager from K--- village cutting fronds that will be used to make the thatch from his plantation of Loh (Cabbage Tree palm) trees. Bamboo must be cut in the forest, then split and shaved to make the frames for the thatch shingles. Photos 6-229 through 6-233 show people representing each house in K--- and M--- villages carrying their quota of thatch and bamboo to the Bilin river to be transported to the Army camp. At the riverbank the materials from several villages are laid out in piles so village leaders can count them (photos 6-234 and 6-235 ); if on arrival at the Army camp they are found to be one household short of the quota, the entire village will be punished. In photo 6-236 , one of many rafts sets out to deliver the materials to the Army camp. These photos were taken between January 8 th and 27 th 2004. Thatch is often demanded by Army camps to repair their own buildings, but when such large quantities are demanded it is possible that the SPDC officers plan to sell it for personal profit. Photos 6-237 through 6-240 in Section 6 and 6-248 through 6-250 below suggest that this may be the case, because they show that Wah Mu army camp demands large quantities of these materials from the villagers at least once every 3 months. [Photos: KHRG]

Photo #9-3: A group of children from P--- village in Dweh Loh township, Papun District await the return of their parents who were forced to supply roofing thatch to a nearby SPDC Army camp. This photo was taken in January 2004. [Photo: KHRG]

Photos #6-25, 6-26, 6-27, 6-28, 6-29, 6-30, 6-31, 6-32, 6-33, 6-34: Villagers in Tantabin township, Toungoo District during two solid weeks of forced labour. On April 1 st 2003, Operations Commander Khin Maung Oo of the SPDC's Southern Command ( Ta Pa Ka ) Strategic Operations Command #3 issued orders for 1,000 villagers from SPDC-controlled villages in the Kler Lah and Kaw Thay Der areas to porter supplies from Kler Lah to Tha Aye Hta Army camp, in order to stockpile enough rations and supplies at Tha Aye Hta in preparation for the coming wet season. Sein Than, commanding officer of IB #75 Company #4 based at Yay Tho Gyi Army camp in Kaw Thay Der, was responsible for rounding up many of the villagers for this labour. It is a six-hour walk from Kler Lah to Tha Aye Hta. For the first two weeks of April, approximately 1,000 villagers had to carry loads in shifts along this route, which is part of the Toungoo – Mawchi vehicle road (see map ). While some villagers carried, others were forced to work clearing the bush along both sides of the road to protect SPDC columns from ambush. These photos taken between April 7 th and 12 th show the villagers travelling up and down the road with loads of Army rations, tools for roadside clearing, and their own food and other supplies. The villagers shown here are from Kler Lah, Kaw Thay Der, Ler Ko, Klay Soe Kee, Wa Tho Ko, and Maw Ko Der villages. Women made up a large portion of the workforce, and there were also children (see photo 6-25 ). They had to bring all their own food and tools, and were paid nothing. The bamboo handles protruding from baskets in photo 6-30 are the handles of their machetes, and in photo 6-25 one man can be seen carrying a two-person saw over his shoulder for clearing trees. Photos of villagers doing clearance work could not be taken because this was done under the watch of SPDC soldiers. The truck in photos 6-31 and 6-32 is owned by 55-year-old villager Saw T--- from K--- village. He was ordered to transport 40 sacks [2000 kg. / 4400 lbs.] of rice from Toungoo town to the Army camp at Tha Aye Hta without payment, not even compensation for the cost of the petrol. In the photos, villagers portering loads are trying to hitch a ride on the truck. Photos 6-33 and 6-34 show a group of villagers bedding down for the night along the roadside, some using their baskets as pillows. [Photos: Tantabin township villagers, assisted by KHRG researcher]

Photo #9-4: On March 15 th 2003, SPDC LIB #434 commander Khin Maung Myint ordered the villagers of B--- village in Dweh Loh township, Papun District to repair the Papun – Ka Ma Maung car road. Many of the adults were busy preparing hill fields for planting season and were not free to go, so they sent their children to go in their place. Twelve-year-old Naw M--- was one of those who had to perform forced labour in her parents' stead. Villagers who had no children had to either go themselves or hire labourers to go in their place. However, at 1,000 Kyat per day for each labourer, this is beyond the means of most villagers. Those who went were forced to supply their own tools and food and were only paid 100 Kyat per day, less than a third of the lowest rate for day labour in Burma. Even so, it is rare for SPDC authorities to pay anything whatsoever for forced labour. Even if it is paid, labour compelled under duress is still considered forced labour and is a violation of international conventions (e.g. ILO Convention 29). Photo #9-5: Naw T---, a 12 year old villager from K--- village in Dweh Loh township, Papun District displays the 100 Kyat note that she was paid by SPDC authorities after performing forced labour rebuilding a road for them in March 2003. In many villages the SPDC demands that each household must supply one worker to report for forced labour, with no exemptions on any grounds. With her father dead and her mother bedridden, Naw T---'s older brother must tend to their hill field while she fills their family's quota for forced labour. The 100 Kyat that she was paid per day amounted to a paltry total of 2,000 Kyat (about US$2 at market rates) at the end of the 20 day work period that she was required to complete. This amount of money is only enough to purchase one big tin [12.5 kgs. / 28 lbs.] of rice, which would only feed their family of three for about one week. The fact that the authorities paid the money directly to Naw T--- demonstrates that they have full knowledge that children are doing the forced labour. Photo #9-6: Eleven year old Naw P--- was ordered by Company Commander Thant Zin from IB #264 to porter rice for SPDC troops from Pa Leh Wah to Klaw Mi Der SPDC Army camp in Toungoo District on March 8 th 2003. The route goes uphill, from the vehicle road in the valley to the hill outpost (see map ). When rations need to be transported to supply Army outposts, SPDC forces are willing to use children rather than make several trips to transport the supplies themselves. [Photos: KHRG]

Photos # 6-248, 6-249, 6-250: Shortly after taking up their post at Wah Mu Army camp in Dweh Loh township of Papun district, SPDC IB #30 ordered these villagers from K--- and M--- villages to supply them with thatch and bamboo. These photos show the villagers in March 2003 carrying the thatch and bamboo to the Bilin riverbank, where they lash it together into rafts and float it downriver to the Army camp. Later in 2003, IB #30 was rotated out of the post and replaced by LIB #349, who continued to issue similar orders to these villagers (See photos 6-228 through 6-236 above and 6-237 through 6-240 in Section 6 ). Photo #6-152: Villagers from D--- village in Bu Tho township of Papun District going to do forced labour for the SPDC in February 2003. They had to sleep on the roadside where they worked for two nights before they were allowed to return home. They had to sleep out on the open ground. The SPDC did not provide them with any form of shelter. Sleeping outside like this without mosquito nets almost guarantees a case of the dangerous strain of Plasmodium Falciparum malaria which is endemic in these hills. They did not receive any payment nor were they even provided with any food while doing the work. Note the two children in the group. [Photos: KHRG]

Photos # 11-37, 11-38, 11-39: On January 4 th 2003, SPDC LIB #341 (Kyaw Mya Thaung commanding) ordered villagers from P--- and K--- villages to carry Army supplies from Hsaw Bweh Der to K'Hee Kyo Army camp in Bu Tho township of Papun District. These girls aged 12, 15, and 20 were part of the group, which had to leave Hsaw Bweh Der at 7 a.m. The soldiers who were supposed to accompany the villagers set out for K'Hee Kyo through the forest, but ordered the villagers to walk along the vehicle road, apparently suspecting that the road may be mined. Shortly before arriving at K'Hee Kyo camp one of the villagers hit a tripwire, detonating a claymore mine placed there by the KNLA. Nine of the villagers were wounded. Photo 11-37 shows Naw A---, age 12, who was hit by shrapnel in the shoulder, left arm, left wrist, and under her breast; medics were later unable to remove the shrapnel, and a month later she said it still made her dizzy often. Beside Naw A--- in Photo 11-38 is Naw B---, 15 (left), who was wounded in the bladder; both girls are shown in school uniform. Photo 11-39 shows 20 year old Naw M---, who sustained shrapnel wounds to her left thigh. Four others were injured more seriously and were sent to the SPDC hospital in Papun town. The use of villagers as human minesweepers is a common SPDC tactic throughout all areas of Karen State. [Photos: KHRG]

Photos # 6-168, 6-169, 6-170, 6-171: On November 14 th 2002, villagers from P--- village were ordered to report to the Twee Thi Oo SPDC Army camp in Dweh Loh township, Papun District to perform loh ah pay . SPDC LIB #534 had given them orders to cut back the scrub from alongside the car road near the camp for three days. The villagers had to take their tools and enough of their own food to last them the three days, knowing that the SPDC would provide them with nothing. Photos 6-168 and 6-169 show the villagers leaving for the camp, carrying food in their baskets. Note the young girls and boys among the group; the young are sent because parents must be in the fields at this time of year to protect the ripening rice grain from animals. Just two days after finishing this forced labour, on November 19 th they were yet again issued forced labour orders from LIB #534. This time they were ordered to clear the brush alongside the Ka Ma Maung – Papun car road at the Htee Ghay Law bridge and to perform any required repairs to the bridge, which they were to carry out with their own repair materials. Photos 6-170 and 6-171 show two of the villagers returning to the bridge with bamboo to make repairs. [Photos: KHRG]

Photos #6-44, 6-45, 6-46: Villagers from K--- village in Dweh Loh township, Papun District portering rice for the DKBA in November 2002. In areas where the DKBA is active, villagers face forced labour demands from them as well as SPDC forces. Note the young child walking with a small load behind the two women in photos 6-45 and 6-46 . Photo #9-7: When villagers in M--- village of Bu Tho township, Papun district were ordered by the local SPDC Army to clear the scrub along the sides of the nearby vehicle road in October 2002, twelve-year-old Naw K--- was the youngest in the group doing the forced labour. SPDC authorities frequently take children for forced labour, or they demand one person per household and the children must go because the parents need to work every day to feed the family. [Photos: KHRG]

Photos # 10-134, 10-135, 10-136, 10-137, 10-138: These villagers in Thaton township of Thaton district left their villages to escape excessive demands for forced labour, money and goods from SPDC and DKBA forces in their area, and now live in the forest where these photos were taken in February 2005. To survive they make and sell roofing thatch. The girl in photo 10-135 has just set down a large basket used to gather leaves for thatch-making. The woman in photo 10-134 is shaving bamboo to make sticks for frames and ties to weave the shingles together, which is being done by the woman in photo 10-136 . In most of the photos, piles of leaves and completed thatch shingles can be seen surrounding the villagers. Each day they must make hundreds of these shingles just to make enough to buy daily rice. It is also a dangerous living; if found living here in the forest by an SPDC or DKBA patrol, they would be rounded up and taken to an Army camp for an indefinite time doing forced labour. [Photos: KHRG]

Photos #1-7, 1-8, 1-9, 1-10, 1-11, 1-12: Several days after the burning of Klaw Lu village (see above), the SPDC column was still in the area so the villagers remained hidden, cooking rice only at night so smoke from cookfires would not give them away. Photos 1-7 and 1-8 show some of the children settling in for the night. Photo 1-9 shows 60-year-old Pi K--- and her husband. They have no children and were unable to carry rice themselves while fleeing, so they had no food and had to share that of others. In photo 1-10 , a Christian pastor who was visiting the area when the villages were invaded gathers the Christian villagers in the forest for a worship service. Naw P---, 46 ( photo 1-11 ), fell sick in the forest and was cared for by other villagers. Naw D---, age 75 ( photo 1-12 ), is blind; when the villagers fled one of her sons (shown here) carried her while the other carried food. All of these photos were taken on November 20 th and 21 st 2004, within three days of the arrival of the SPDC column in the area. [Photos: KHRG]

Photos #1-13, 1-14, 1-15, 1-16: By November 21 st 2004, three days after SPDC LIB #589 had entered the area, the villagers from Klaw Lu, K'Hee Day and Khaw Hta were weaving thatch for roofing ( photo 1-15 ) and building shelters. Saw G---, 40, was building a shelter along with his pregnant wife ( photo 1-13 ); he said their house in Khaw Hta had been burned by LIB #589. Small children and pregnant women were given priority for the first shelters built. Photo #1-22: On November 23 rd 2004, villagers from L---, in the same area of Shwegyin township as the villages already burned, hurry to harvest as much paddy as they can. They were afraid that the LIB #589 column would come to destroy their village and fields any day. Even so their children remained in school, only coming into the fields to help with the harvest after school ended each day. [Photos: KHRG]

Photos # 10-12, 10-13, 10-14, 10-15: Displaced villagers from Sho Hser village, along the Toungoo-Mawchi vehicle road on the Karen/Kayah State border, in August 2004. They had to flee their village due to increasing SPDC militarisation of the area along the road, and now live in hiding here in the forested hills. Photos 10-12 and 10-13 show some of their forest shelters. In photo 10-14 , a man carries drinking water from the stream in several hollow segments of bamboo. For children, the need to play still continues ( photo 10-15 ). [Photos: KHRG]

Photo #9-8: Displaced in January 2004 by SPDC LIB #117 forces militarising the area around the Toungoo-Mawchi vehicle road and trying to flush Karen and displaced Karenni villagers out of the hills, these Karen children from T--- village in Toungoo District wait in their hiding site in the forest for their parents to return from foraging for food. Photo #10-39: A mother with a newborn infant takes a rest while fleeing into the forest with other villagers on January 16 th 2004. She is from K--- village in Tantabin township, Toungoo district. Photo #9-9: Children displaced from K--- village in Toungoo District in January 2004 display simple toys they have made from surgical gloves given to them by a Karen mobile medical team. Villagers displaced in the forests struggle not only for survival, but for a continuation of dignity and community, and they see education and play as crucial elements in this struggle. [Photos: KHRG]

Photos #10-70, 10-71: In January 2004, the SPDC launched a full military offensive in southern Karenni (Kayah) State, using the informal ceasefire with the KNU as protection for their southern flank so they could attack forces of the KNPP (Karenni National Progressive Party) and forcibly relocate Karenni civilians into SPDC-controlled sites. SPDC LID #55 was moved in to the area along the recently completed Toungoo to Mawchi vehicle road which passes through Toungoo District. The offensive spilled over into Toungoo and Papun Districts of Karen State after the SPDC soldiers pursued Karenni villagers who sought to avoid internment in relocation sites by fleeing into northern Karen State. As SPDC units swept through the area, many Karen villagers also fled their villages. These photos show Karenni villagers who fled the SPDC campaign in southern Kayah State into the forests of Toungoo district in Karen State in January 2004. Photo #10-69: Karenni children on the run from SPDC Light Infantry Division #55 in the forest of northern Papun district on January 9 th 2004. [Photos: KHRG]

Photos #10-47, 10-48, 10-49, 10-50, 10-51, 10-52, 10-53, 10-54, 10-55, 10-56: Villagers throughout Lu Thaw township of Papun district fled their villages as mobile SPDC columns sought to catch them in their villages in January 2004. The people of K--- village fled on January 8 th (photos 10-47 and 10-48 ); from L---, M---, and T--- villages also on January 8 th (photos 10-49 through 10-51 ); from P--- village, on January 11 th ( photo 10-52 ); from K--- village on January 18 th ( photo 10-53 ); and from H--- village on January 18 th (photos 10-54 and 10-55 ). Photo 10-56 shows some of the displaced villagers who have gathered at one hiding site arriving to meet with local KNLA officers to get information on SPDC movements and to request medicine for the sick. [Photos: KHRG]

Photos #10-43, 10-44, 10-45, 10-46: Villagers flee K'Leh Loh village in Lu Thaw township, Papun district to escape an approaching column of Light Infantry Division #55 in January 2004. The column entered their village, burned their paddy storage barns, looted their houses, and killed villager Saw Kloh Po Heh. Photo #10-76: A family from T--- village in northern Papun district staying in their hillfield hut on December 24 th 2003, in the hope that they will not be found there by SPDC Light Infantry Division #55. [Photos: KHRG]

Photo #10-146: When her husband fell ill and died for lack of medicine, Naw P--- was left alone to care for her 4 children, aged 3, 6, 8, and 10 when this photo was taken in October 2003. They were living as internally displaced people because they no longer dared stay in their village in Lu Thaw township, Papun district. Photo #9-10: These children are playing in the burned remains of their homes in T--- village, Ler Doh township, Nyaunglebin District after it was burned by soldiers from SPDC LIB #119 and LIB #109 on May 17 th 2003. After villages are burned and the troops withdraw, villagers usually return to see what can be salvaged. Knowing this, SPDC troops sometimes leave landmines among the burned ruins. To the children it can all seem like an adventure at first, but this form of play is dangerous. Photo #9-11: On March 4 th 2003, SPDC soldiers from LIB #6 and IB #14 burned Ho Kay village in Bu Tho township, Papun District. All of the villagers fled from their village and resettled in temporary settlements in the forests. Some of the villagers crossed the Salween River into Thailand. See also photos 2-15 through 2-17 in Section 2 and 10-164 through 10-169 in Section 10 . [Photos: KHRG]

Photo #9-12: On January 15 th 2003 SPDC troops from LIB #434 passed through villages in Bwa Der village tract of Bu Tho township, Papun district on their way to a post on the Salween River (see also photos 10-107 through 10-113 in Section 10 ), causing villagers throughout the area to flee into the forest to avoid capture. These two children from N--- village were among those who became internally displaced persons when they fled with their families. Photo #9-13: These children from G--- village in Papun District were forced to flee with their parents when SPDC Army soldiers entered their village early in 2003. They were still living in the forest when this photo was taken in February 2003. Photo #4-14: 35-year-old Naw E--- from P--- village in Ler Doh township of Nyaunglebin District was arrested, interrogated and beaten by soldiers from SPDC IB #60 because her husband works with the KNU. She is shown here with her three children, who had to flee with her in order to avoid further repercussions. This photo was taken in February 2003. [Photos: KHRG]

Photos #10-162, 10-163: These families are from P--- village in Kawkareik township and K--- village in Kya In township, Dooplaya district. In January 2003 they could no longer abide the forced labour and arbitrary abuses and demands imposed on them by the SPDC forces controlling their area, so they fled across the border to Thailand. They were promptly forcibly repatriated by Thai authorities, however, and when these photos were taken they had just arrived back in Karen State and were wandering uncertain where to go; they told a KHRG researcher they had "No money to pay and no land to stay." Photo #9-14: An internally displaced child returning to his IDP site in Than Daung township in Toungoo District with water that he had just collected from a nearby stream in November 2002. IDPs must exercise extreme caution when doing this as the SPDC has been known to plant landmines on the paths that they know civilians use when going to buy food, collect water, or when going to their plantations. The area to the east of the Day Loh River, where this photo was taken, is known to suffer heavily from landmine contamination. [Photos: KHRG]

Photo #10-115: Internally displaced villagers from Thaw Ngeh Der village in Ler Doh (Kyauk Kyi) township of Nyaunglebin District. As a part of the SPDC's ongoing campaign to depopulate the hills of Nyaunglebin District, on October 5 th 2002 soldiers from LIB #175 entered their village and burned it to the ground, while all the villagers fled into the forest. This is not the first time that this had happened; three and a half years earlier in May 1999, a column of soldiers from IB #48 and IB #26 had done the exact same thing, burning the village and all food supplies to the ground. Theirs was only one of a dozen such villages that were destroyed. Over the past twenty years many villagers in Karen regions have gone through repeated cycles of village destruction by SPDC forces, life displaced in the forests, and gradual re-establishment of their villages only to have them burned again. This photo was taken three days after the attack on their village, when the people were returning to the village to rebuild their homes. See also photos 10-116 and 10-117 . Photos #10-116, 10-117: Children in Kyauk Kyi (Ler Doh) township, Nyaunglebin district, move through the forest with their families in October 2002 after SPDC units burned their farmfield huts and came to their villages. These children from Dta Kaw Der village were fleeing through the forest on October 9 th 2002 after SPDC troops had destroyed their village. See also photo 10-115 . [Photos: KHRG]

Photos #10-123, 10-124, 10-125, 10-126, 10-127, 10-128: Naw K--- (photos 10-123 through 10-126 ) transports her whole family and some of their belongings across the Thi Roh river in Papun district in August 2002. Two weeks earlier, SPDC soldiers from Light Infantry Division #44, Military Operations Command #2, LIB #9, had come to her village led by deputy battalion commander Myo Myint. They stayed in the village only a day, but threatened the villagers and told them, "After we leave, another unit will come." The villagers didn't wait to see, they left for the hills. Naw K--- had to do everything herself because her husband was not at home. The women from her village shown in photo 10-128 said that several of them had done the same; families were divided in the hurry to leave the village. [Photos: KHRG]

Photo #9-16: Unable to continue enduring the conditions experienced in their villages any longer, many villagers adopt a life of uncertainty, living as internally displaced persons (IDPs) hiding in the forests. These children were photographed in July 2002 in their hidden IDP site in Lu Thaw township, Papun District. [Photo: KHRG; disregard the date printed on the photo.]

Photos #10-182, 10-183, 10-184, 10-185, 10-186, 10-187, 10-188, 10-189, 10-190, 10-191, 10-192, 10-193, 10-194: Villagers who manage to cross into Thailand, avoid forced repatriation by Thai authorities, and find their way into a Karen or Karenni refugee camp are still not safe. Since 1995, Thai authorities have consolidated the refugee camps and progressively moved them closer to the border (contrary to established UN refugee guidelines) and onto more unstable and unlivable terrain, as part of a deliberate policy to make life difficult and dangerous for refugees in the hope that they will decide to return to Burma instead. One result has been attacks by Burmese forces on unprotected refugee camps; another has been deaths by natural disasters due to the placement of refugee camps in steep and unstable gullies. On September 2 nd 2002, flash floods swept away houses in Meh Ka Kee (Mae Khong Kha) Karen refugee camp opposite northern Pa'an district, killing at least nine refugees. Photos 10-182 through 10-184 show the waters raging through the camp. Photo 10-185 shows all that remains of a house that stood in the way, and photo 10-186 shows the remains of the barracks for newly arrived refugees. Those killed included Naw Lah May, 17 ( photo 10-187 ); Saw Tah Pu Lu, 14 ( photo 10-188 ); Saw Hsa K'Pru, 26; Saw Kyaw Ta Muh, 19 ( photo 10-189 ); Naw Wah, 12 ( photo 10-190 ); Naw Lay Way Paw, 18 ( photo 10-191 ); Naw Mu Si Si, 10 ( photo 10-192 ); Saw Johnson Mu, 19 ( photo 10-193 ); and Saw Kyaw Htoo, 49 ( photo 10-194 ). The camp is built along steep and narrow gullies extremely vulnerable to flash floods and landslides. Making matters worse, when floodwaters rise Thai authorities sometimes open the dam upstream at Mae Sariang without notifying villagers or refugees downstream. This has caused deaths in villages near Meh Ka Kee in the past, though it is not confirmed whether it happened in this case. [Photos: KHRG]

Photo #9-17: Naw H--- is an IDP living in hiding in the forests of Tantabin Township of Toungoo District. Her mother died when she was only two months old, so her grandmother now takes care of her. This photo was taken in June 2004. Photos #9-18, 9-19: Saw P---, 12 years old when these photos were taken early in 2004, became fatherless at age nine when SPDC soldiers shot his father dead in his hill field in Papun District. Without a father, he must now work selling his services as a day labourer to help provide food and clothing for his mother and younger siblings. Photo 9-18 shows him ploughing a sugar cane plantation. Photo 9-19 was taken while he was boiling jaggery (crystallised from cane juice) for a fellow villager. Many children who lose their parents find themselves in similar situations. Photo #5-12: Heavily pregnant Naw L---, 27, from T--- village in Bilin township of Thaton District became a widow and single mother when her husband was shot dead by DKBA soldiers from #333 Brigade, 2 nd Special Battalion Company 1, led by Saw Bu Ghay. Her husband was on his way to worship at 10 a.m. on August 17 th 2003 with a group accompanied by a KNLA escort when they encountered DKBA soldiers at Wa Klay Kyo. He was shot six times; once in the face, once in the chest, once in the armpit, once in his leg, and twice in his back. She told KHRG, "I have no husband anymore, so how can I work for food? My child is small, I can't work. I get angry with them [DKBA] when I think about my husband." This photo was taken in January 2004. Photo #5-13: At 10 p.m. on August 9 th 2003, soldiers from SPDC LIB #434 (Battalion Commander San Aung commanding) captured a number of internally displaced villagers from K--- village in Dweh Loh township, Papun District. They accused the villagers of being KNU sympathisers and then executed some of them. This photo shows the widows of three of the men executed: from left to right, 24 year old Naw B--- who is eight months pregnant, Naw M---, 32, also heavily pregnant, and 23 year old Naw E---. Along with being displaced, they now have to provide for their children alone. This photo was taken in September 2003. [Photos: KHRG]

Photos #5-20, 5-21, 5-22: Saw Pa La Day, 50, from T--- village in Bu Tho township of Papun District was shot dead on sight by soldiers from SPDC Light Infantry Division #66 on May 30, 2003. His wife, Naw T--- ( Photo 5-22 , which has been damaged), must now raise their three young children alone. The SPDC has been trying to depopulate the hills of Bu Tho township since 1997 by burning villages and shooting villagers on sight. These photos were taken in June 2003. Photo #4-13: Naw N--- is a 33-year-old widow from W--- village in Bu Tho township of Papun District. On May 5 th 2003, soldiers from LIB #434 led by Myo Myint Hlaing were ambushed by KNLA soldiers not far from her village. The soldiers then entered the village and arrested Naw N---'s husband, 41 year old Pa M---, and accused him of complicity in the attack. Arbitrarily arresting local fighting-age male villagers in retaliation for ambushes is a routine SPDC Army procedure. During his interrogation at the SPDC Army camp nearby, Pa M--- was kicked, strangled, hung, stabbed in the legs with knives, and beaten to death. Their eldest daughter, 13 year old Ma M---, had to drop out of school in order to find work to help her mother raise money to support the family. This photo was taken in July 2003. [Photos: KHRG]

Photos #9-20, 9-21: These two brothers from D--- village in Bu Tho township of Papun District, Saw G---, age 8 (left), and Saw S---, age 4 (right), must live with their grandparents because both of their parents are dead. Their mother died in August 2001 after eating a poisonous toad while working in her hill field. For the next 18 months their father looked after them alone until he was captured and killed by SPDC troops on January 7 th 2003. Villagers from the area reported the incident to the local SPDC Army battalion, but no compensation was paid for his death or to support the children. Since then, the boys cry whenever their playmates are called home by their parents, because they no longer have any parents to call them home. Their grandparents say they were already struggling to support themselves, and it is now an added struggle to support the boys as well. These photos were taken in February 2003. Photo #5-30: After her husband was shot dead on sight by SPDC troops in November 2002, this woman and her child from D--- village in Papun District moved to stay with another family in M--- village, where this picture was taken. Photos #5-31, 5-32: On November 4 th 2002, Saw L---, Saw P---, and Saw Sha Kaw from D--- village in Lu Thaw township, Papun District left their village to sell bamboo that they had cut. They were spotted by soldiers from SPDC IB #19 who opened fire on them, wounding Saw L--- and killing Saw Sha Kaw. Photo 5-31 shows 27 year old Saw L--- receiving medical attention for the gunshot wounds in his shoulder at a KNU clinic in the area. Photo 5-32 is of Saw Sha Kaw's wife and four children. With her children still too small to do much hard work in the hill fields, it will be difficult for her to grow enough food for her family. SPDC forces routinely shoot villagers on sight in this area, because they have never been able to bring it under their full control. [Photos: KHRG]