Since 1997, all villages in rural Karen areas not situated directly adjacent to a motor road or SPDC Army camp have been ordered to relocate to sites under direct SPDC military control. This can be an empty field beside a road or Army camp, or adjacent to an SPDC-garrisoned village. Villagers are rarely given more than a week to move, and are sometimes ordered at gunpoint to move immediately without time to collect all of their belongings, most villagers are forced to leave behind whatever they are unable to carry with them – most of which is later looted by SPDC patrols, who also burn the houses and sometimes landmine the ruins of the village to prevent any possibility of the villagers' return. Many villagers flee to remoter areas rather than move to the relocation sites, but they are then vulnerable to being shot on sight by SPDC patrols. The result observed across Karen State of the forced relocations and restrictions is a combination of feudal-style fenced-in villages along roadways controlled by SPDC Army camps, hills dotted with abandoned or destroyed villages, and tens of thousands of internally displaced villagers living in hiding in the forests.

To exert control over civilian populations, SPDC authorities and the military impose heavy restrictions on people's movement and activities. Villages lying outside the easy reach (and therefore control) of the Army are given orders to relocate to Army-accessible sites, such as existing villages along military roads, or even to sites directly adjacent to Army camps. The history of relocation campaigns which affect hundreds of villages in areas where there is only limited resistance activity, and even in some of Burma's urban areas, indicates that relocation is not simply a strategy to cut off civilians from resistance forces (as is frequently claimed), but a strategy aiming for absolute military sovereignty over all of Burma's civilians regardless of the presence of resistance forces.

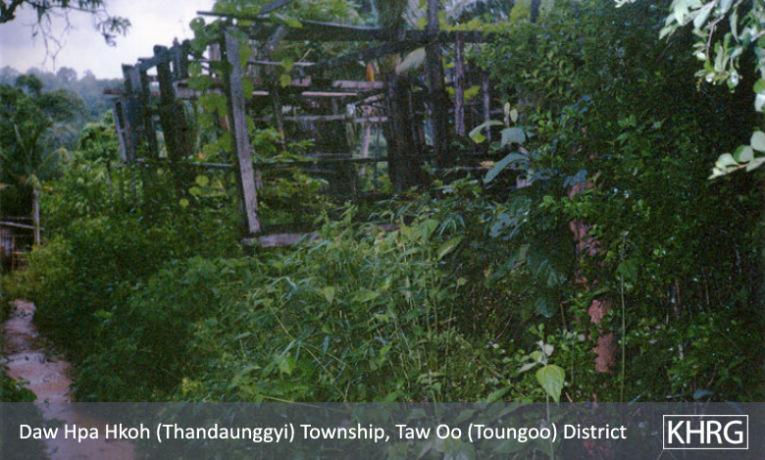

Since 1997, all villages in rural Karen areas not situated directly adjacent to a motor road or SPDC Army camp have been ordered to relocate to sites under direct SPDC military control. This can be an empty field beside a road or Army camp, or adjacent to an SPDC-garrisoned village. Villagers are rarely given more than a week to move, and are sometimes ordered at gunpoint to move immediately (see photos 3-18 to 3-20 , 3-21 to 3-26 , 2-37 to 2-40 and 2-41 and 2-42 ). Without time to collect all of their belongings, most villagers are forced to leave behind whatever they are unable to carry with them – most of which is later looted by SPDC patrols, who also burn the houses and sometimes landmine the ruins of the village to prevent any possibility of the villagers' return (see photo 3-3 ). Additional photos on SPDC destruction of relocated villages can be seen in Section 2 ( Attacks on Villages and Village Destruction ). Many villagers flee to remoter areas rather than move to the relocation sites (see photo 10-122 ), but they are then vulnerable to being shot on sight by SPDC patrols, as happened to the villagers in photos 5-67 to 5-72 . As a result, villages throughout the hills of Karen areas lie abandoned ( photos 3-4 to 3-9 , 3-13 to 3-15 , and 3-18 to 3-20 ), much of their population living nearby in hiding but no longer able to stay openly in an undefended village. Sometimes these villages are home to abandoned and wandering cattle ( photos 3-18 to 3-20 ), or in the case of K--- village in Toungoo district ( photos 10-28 and 10-29 ), a message scrawled in charcoal by an SPDC soldier expressing his remorse at what his unit has done.

Relocation sites are usually on land compensated without compensation from other villagers, often ricefields which flood in the annual rains (photos 3-1 and 3-10 to 3-12 ). Villagers moving here are supplied with nothing; they must build their own houses from their own materials, find their own food, and no schools, health facilities or clean water supplies are established. Moreover, they are used as a convenient pool of forced labour by local military units (photos 3-2 , 3-21 to 3-26 , and 10-174 to 10-181 ). To survive, people must forage around the SPDC-controlled village or seek work as daily wage labourers, because no land is available for farming and they are usually not allowed to return to their home fields. As a result many flee these sites within weeks or months, preferring to face the dangers around their home villages or trying to cross the border to become refugees ( photos 10-174 to 10-181 ).

In many SPDC-controlled villages and relocation sites people have now been forced to fence themselves in, leaving only one or two gates by which people can enter or leave the village (photos 6-195 and 6-193 ). Supposedly to 'keep rebels out', these fences function more to keep villagers in, particularly when SPDC units come to round up people for forced labour; while a few troops block the gates, the others sweep the village to catch people. No one is allowed to leave these villages without a pass, particularly if they need to travel to market or to distant farmfields. Travel passes must be obtained from local military officers, who charge varying prices for them (see photos 3-16 and 3-17 ). In many cases they only allow villagers to be out from dawn to dusk, and even specify how much rice they are allowed to carry with them. The rigidity of such restrictions makes it extremely difficult for people to farm, as Karen villagers often tend fields quite far from their villages and traditionally live in huts in their fields through much of the growing season.

The result observed across Karen State of the forced relocations and restrictions is a combination of feudal-style fenced-in villages along roadways controlled by SPDC Army camps, hills dotted with abandoned or destroyed villages, and tens of thousands of internally displaced villagers living in hiding in the forests.

Photo #3-1: Taken in October 2004, this shows part of a relocation site at Naw Htaw Pwa in Nyaunglebin District. Several villages were forced to move here earlier in 2004. Villagers from this site are used for forced labour by SPDC Operations Commander Khin Maung Oo (see photo 3-2 ). [Photo: KHRG researcher]

Photo # 3-2: Villagers at Naw Htaw Pwa relocation site in Nyaunglebin District (see photo 3-1 ) spread out along the dirt road to do forced labour cutting and clearing scrub from the roadsides on October 12 th 2004, under orders from SPDC Operations Commander Khin Maung Oo. These people were forced to move from their homes in S--- and P--- villages to the relocation site earlier in 2004 and are now regularly used for forced labour. Villagers are forced to clear scrub from roadsides as a security measure to protect SPDC vehicles from ambush. They are provided with no tools and must clear even trees and dense scrub with nothing but machetes. Most of the workers in this photo are women. [Photo: KHRG researcher]

Photo # 3-3: Saw T---, age 40, from T'Nay Hsah township, Pa'an District fled to a refugee camp in Thailand with his family after DKBA soldiers relocated them and planted landmines in their village. On May 16 th 2004, soldiers from DKBA #999 Brigade Special Battalion forcibly relocated a number of villages in T'Nay Hsah township of Pa'an District to nearby Wah Klu Pu village. After the villagers had been relocated the soldiers planted many landmines on the paths leading into their home villages and in the villages themselves to deter the villagers from returning. As a result, the villagers no longer dare to return to their homes to collect their food or any of their belongings for fear of stepping on one of the mines. This photo was taken in July 2004. [Photo: KHRG researcher]

Photos # 3-4, 3-5, 3-6, 3-7, 3-8, 3-9: On February 10 th 2004, G--- village in Nyaunglebin District was forced to relocate by SPDC LIB #599, under the orders of Bo Pyi Sone and Sgt. Nyi Nyi. These photos were taken two months later, when some of the villagers managed to revisit the village they had been forced to dismantle. Photo 3-6 shows the abandoned Catholic Church. Naw Y---, age 80 ( photo 3-9 ), is from a nearby village and was unable to walk to the relocation site so she must stay behind alone. Note that this relocation occurred over a month after the informal KNU-SPDC ceasefire came into effect. The photos immediately below show the relocation site. [Photos: KHRG researcher]

Photos # 3-10, 3-11, 3-12: Photo 3-10 shows the relocation site in Nyaunglebin district where the people of G--- village (see photos 3-4 through 3-9 ) have been forced to live since February 10 th 2004. It lies along a roadside between two villages in what used to be irrigated ricefields, which flood in rainy season. To place the relocation site, the Army confiscated these ricefields without compensation from Saw H---, 70 ( photo 3-11 ) and Saw K---, 30 ( photo 3-12 ). Both men say that with the relocation site lying on their fields, they can no longer farm and have lost their livelihood. [Photo: KHRG researcher]

Photos # 10-28, 10-29: These photos show a message of remorse written in charcoal on an abandoned villager's house by an SPDC soldier from the unit that forced them to relocate. When IB #39 ordered K--- village in Toungoo district to relocate, the villagers fled into the hills instead and had not yet returned when this photo was taken in February 2004. On the abandoned house of a girl he clearly liked, this soldier wrote: "To Ma C---, full of remembrance I have written this note. When I arrived at little sister's [your] village, I imagined little sister. [I] Remember the place where [I saw you] wearing [your] skirt. But I'm sorry that we can't do anything. I am sorry. That is all. IB #39, H---." Photo 10-28 shows the entire note; photo 10-29 focuses on the second half more clearly. [Photos: KHRG researcher]

Photos # 3-13, 3-14, 3-15: Abandoned homes in Than Daung Township, Toungoo District. The two villages in these photos were relocated to the Kler Lah relocation site. Both of these villages have been forcibly relocated on numerous occasions over the past ten years. Photo 3-13 , taken in May 2003, shows part of what remains of Der Doh village, while photos 3-14 and 3-15 , taken in August 2003, are of nearby Ku Pler Der village, which since being relocated has been rapidly overgrown by the forest. Many villages in Toungoo District have been forcibly relocated to one of the SPDC-garrisoned relocation sites, where soldiers can exert authority over the villagers and use them as a ready source of forced labour and extortion money. [Photo: KHRG researcher]

Photo # 3-16: People from a village in Dweh Loh township, Papun District on their way to the nearby SPDC Army camp at M--- to obtain a travel pass from Major N--- of SPDC IB #57. Villagers living in SPDC controlled areas have no freedom of movement. Prior to being allowed to leave their village, they must tell the local SPDC Army commander where they are going, who they are going with, and why they are going there. Depending on whether or not the commander accepts their reasons, he may or may not then issue them with a travel pass. Whenever a villager is caught beyond the boundaries of their village without a travel pass, they are arrested as KNU sympathisers and beaten, often with sticks and the butts of the soldiers' rifles. This photo was taken in June 2003. [Photo: KHRG researcher]

Photo # 3-17: An example of a travel pass that many villagers across Karen State must obtain from local SPDC authorities or Army battalions before leaving their village. Travel passes, like this one from Dweh Loh township of Papun District, are only issued after the payment of a fee, usually ranging from 50 to 200 Kyat each. This pass from May 2003 states that the villager named therein is doing work repairing paddy dikes and farmfield huts and asks any authority encountering him not to harm him. However, it is issued by a village-level PDC authority rather than the Army, and may not be respected by Army patrols. [Photo: KHRG researcher]

Photo # 6-195: SPDC soldiers ordered the villagers from M--- village in Bu Tho township, Papun District to construct this bamboo fence around their village and monastery. Many villages across Karen State have been ordered to fence themselves in with only one or two gates for entrance and exit. The stated purpose of these fences is to keep Karen resistance forces out of the village, but they are more often used when SPDC Army columns arrive at the village – by blocking off the gates they can trap the villagers inside, making it easy to round up forced labourers and loot the villagers' belongings, or to capture village leaders for interrogation. This photo was taken in March 2003. [Photo: KHRG researcher]

Photo # 6-193: DKBA soldiers forced villagers in Papun town to construct this security fence; whether its purpose is to keep KNLA forces out or villagers in remains unclear. This photo was taken in October 2003. [Photo: KHRG researcher]

Photo # 10-122: Karenni villager Saw R---, 41, and his children are from Baw Gho Der township in southern Karenni (Kayah) State but he says they have fled to northern Karen State several times over the years. When this photo was taken in late 2002, he said the SPDC had ordered his village to move to Mawchi town, but the villagers didn't trust them so they didn't obey. He told a KHRG researcher, "We have suffered a lot from SPDC persecution. They eat and burn our paddy, rice, food and poultry. They have killed some of us. We have to flee them and hide in the forest." [Photo: KHRG researcher]

Photos # 3-18, 3-19, 3-20: On April 19 th 2002, the village heads from Htee Pway Leh, K'Leh Ta Mu and Htee Ghaw villages in Kya In township, Dooplaya District were summoned to a meeting by battalion commander Major Min Din of LIB #301. The battalion commander berated them and accused them of supporting the resistance, saying, "Your villagers make contact with the Kawthoolei [KNLA] soldiers. Your villagers encourage, feed, and support them. ... The Kawthoolei soldiers come to shelter in your villages." He then ordered all three villages to move within two weeks to Kyone Sein relocation site, and decreed that anyone remaining behind in the villages after the deadline would have "harsh action" taken against them. This is usually interpreted to mean detention, beatings, torture and possible execution. These photos show Htee Ghaw village after it had been abandoned. Some villagers had managed to strip and carry the walls, floor or roof of their house so they could rebuild in the relocation site (one family took everything but the posts, as shown in photo 3-20 ), but many did not have time to take all their livestock and belongings. Cooking pots and baskets of possessions that the villagers were unable to take with them remain in the some of the huts, as can be seen in photo 3-19 . Any food supplies or livestock left behind will be looted or destroyed by SPDC patrols before long. These photos were taken in May 2002. See also photos 3-21 through 3-26 below, depicting the relocation of Htee P'Nweh village. [Photos: KHRG researcher]

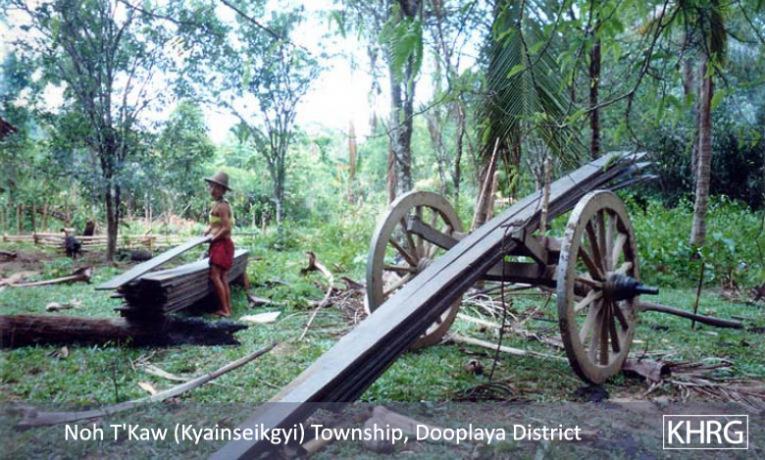

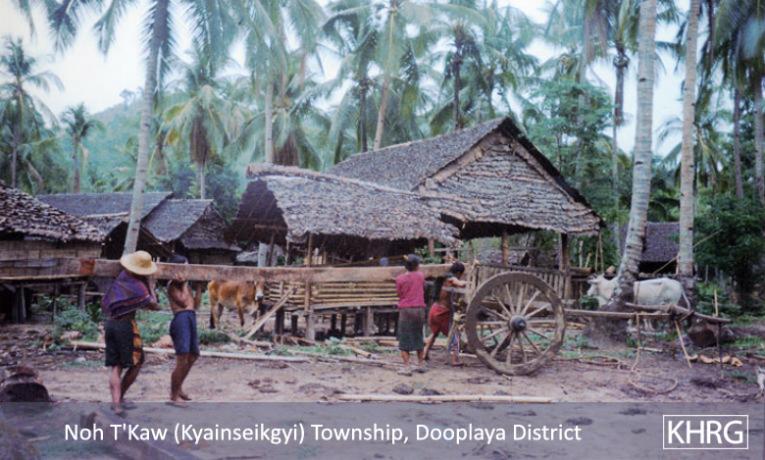

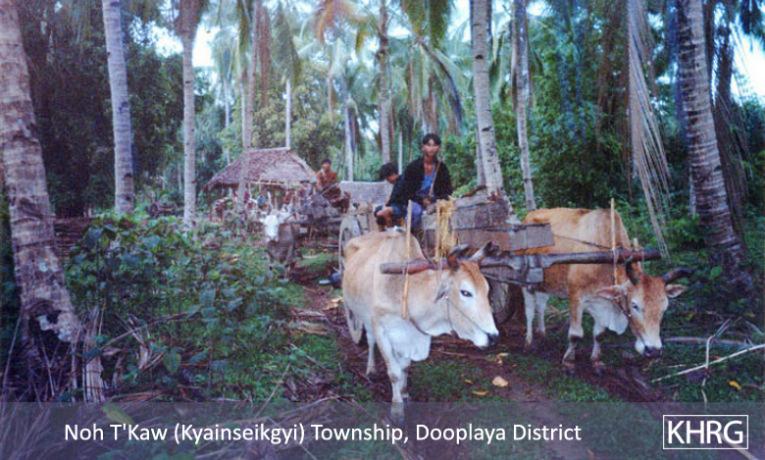

Photos # 3-21, 3-22, 3-23, 3-24, 3-25, 3-26: Htee P'Nweh village was not included in Major Min Din's meeting of April 19 th 2002 (see above) when he ordered several villages to move. However, on May 8, Min Din led his troops into Htee P'Nweh village without warning, and opened fire on villagers who tried to flee (see photo 5-63 ). He then accused the villagers of harbouring Karen resistance forces and ordered everyone to move to Meh T'Kreh relocation site within 2 weeks. His soldiers immediately burned down 10 houses and threatened to burn the rest if anyone remained the next time they returned. In the photos, villagers are preparing to haul their belongings and building materials they've stripped from their houses on bullock carts to Meh T'Kreh relocation site. Many villagers who had no access to bullock carts fled into the forest to live as IDPs, some of whom then fled to one of the refugee camps in Thailand. One villager from P--- village who went to the relocation site but later fled to Thailand told KHRG, "The people were faced with many problems, but they [SPDC Army soldiers] forced the people to move quickly. They said, 'If you don't move quickly, I will come and burn all of your houses'. ... The SPDC didn't support the people. The villagers had to do everything for themselves. They didn't give us logs, bamboo or thatch at the relocation site. The villagers had to find the thatch themselves and cut the logs and bamboo themselves. ... We had to live among other people. It was very crowded. ... There is enough water there during the rainy season, but during the dry season water becomes scarce." See also photos 3-18 through 3-20 above. [Photos: KHRG researcher]

Photo # 5-63: On May 8 th 2002, soldiers from LIB #301 commanded by Battalion Commander Min Din entered Htee P'Nweh village in Kya In township of Dooplaya District. Village elder Saw P---, age 40, tried to flee the village but was gunned down by the soldiers, hit by bullets in both thighs and his right ankle. The soldiers then accused the villagers of harbouring Karen resistance forces, ordered them to move to Meh T'Kreh relocation site within two weeks, and burned 10 of the village houses (see photos 2-41 and 2-42 and 3-21 through 3-26 ). Saw P--- was left without treatment, and had to be treated by the villagers. [Photo: KHRG researcher]

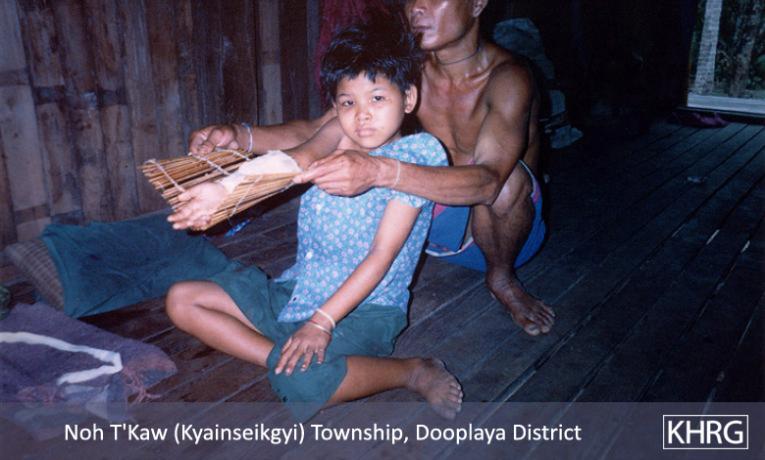

Photos # 2-37, 2-38, 2-39, 2-40: At a meeting on April 19 th 2002, battalion commander Major Min Din of SPDC LIB #301 began ordering villages in Kya In township of Dooplaya district to move to Kyone Sein and Meh T'Kreh relocation sites. Kaw Kheh village was not called to that meeting, but suddenly on April 28 th 2002 Major Min Din and his troops arrived in the village, accused the villagers of harbouring Karen resistance forces, and by 6 p.m. they had burned most of the houses, the church, and the community religious hall to the ground. Before leaving, they told the villagers they had 2 weeks to move to Meh T'Kreh or face "harsh action". Photo 2-38 depicts one of the villagers and his daughter standing in front of the remains of what was their home, while photos 2-39 and 2-40 show the remains of Naw T---'s house and paddy barn. See also photos 2-41 and 2-42 below showing the burning of Htee P'Nweh village, and photos 3-18 through 3-26, which show the relocation of Htee Ghaw and Htee P'Nweh villages. These photos were taken in May 2002. [Photos: KHRG researcher]

Photos # 2-41, 2-42: Like Kaw Kheh (see above), Htee P'Nweh village was not called to Major Min Din's April 19 th 2002 meeting to receive a relocation order. Instead, Min Din and his troops arrived in the village without warning on May 8 th and opened fire on villagers who tried to flee (see photo 5-63 ). He then accused the villagers of harbouring Karen resistance forces and ordered everyone to move to Meh T'Kreh relocation site within 2 weeks. His soldiers immediately burned down 10 houses and threatened to burn the rest if anyone remained the next time they returned. The photos show the remains of the 10 burned houses. After being ordered to move to Meh T'Kreh, the villagers dismantled their houses and transported their belongings to the relocation site (see photos 3-21 through 3-26. These photos were taken in May 2002. [Photos: KHRG researcher]

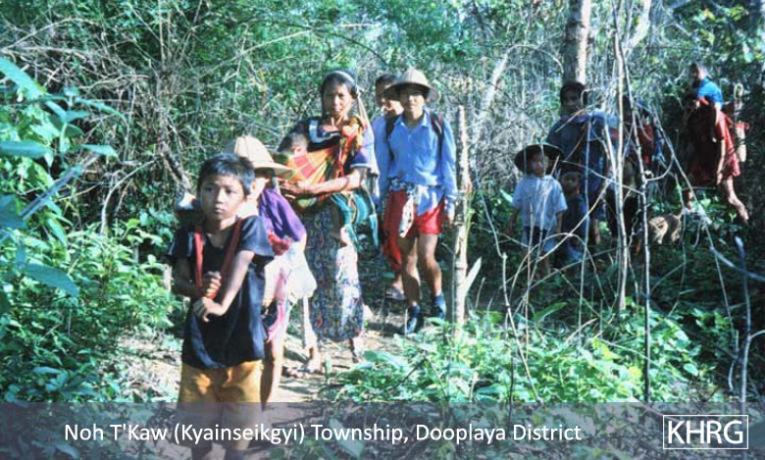

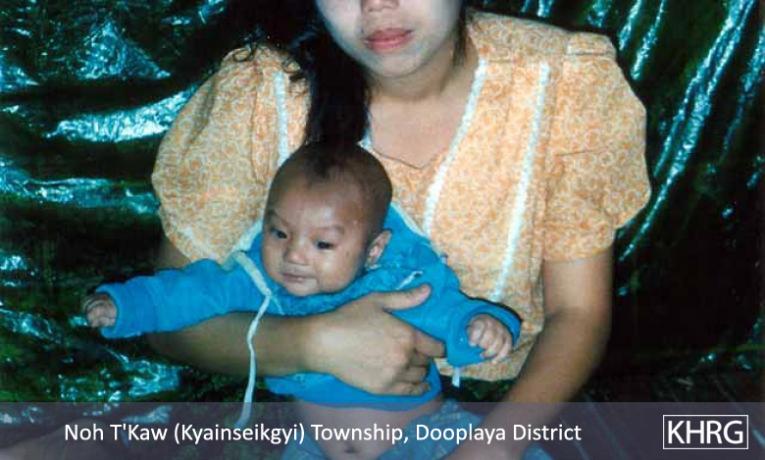

Photos # 10-174, 10-175, 10-176, 10-177, 10-178, 10-179, 10-180, 10-181: Villagers fleeing forced relocation in Kya In township, Dooplaya District in mid-2002. On February 24 th , SPDC IB #78, IB #77, and LIB #83 ordered all villages in Ta Gu Kee area to move to Meh T'Kreh and said they would shoot on sight anyone who remained. Between April 27 th and May 12 th , troops from SPDC LIB #301, LIB #416, and IB #78 entered Tee Th'Blu, Kaw Keh, Tee P'Nweh, Paw Ner Mu, Done P'Loung, and Tee Khaing villages, ordered the villagers out without specifying a destination, and burned their houses, schools, churches and food supplies. As a result, hundreds of villagers fled to Noh Po refugee camp in Thailand. Photos 10-174 through 10-177 show them heading for the Thai border in late May and early June 2002. Photo 10-178 shows a group that had just arrived at the refugee camp in late May. Photo 10-179 shows Naw H--- and her family; when IB #78 ordered their village of Tee Law P'Leh to move within 4 days to Lay Wah Kah on April 27 th , they obeyed, but after two weeks doing forced labour every day and without proper shelter, food or medical help at the relocation site, they fled to Thailand in mid-June. After three months at a relocation site, Saw P--- and his family ( photo 10-180 ) also fled in mid-June, saying there was no way of surviving at the site and they were forced to work constantly for the Army. Naw P---, 23 ( photo 10-181 ), fled with her baby in June after two weeks at Meh T'Kreh relocation site for the same reasons. [Photos: KHRG researcher]

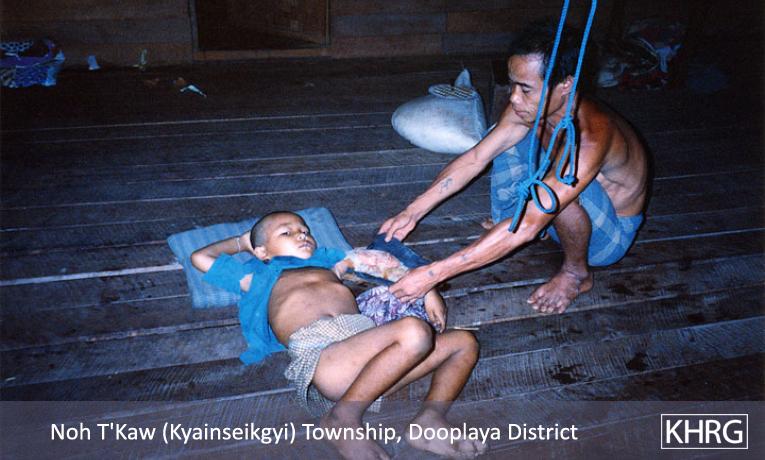

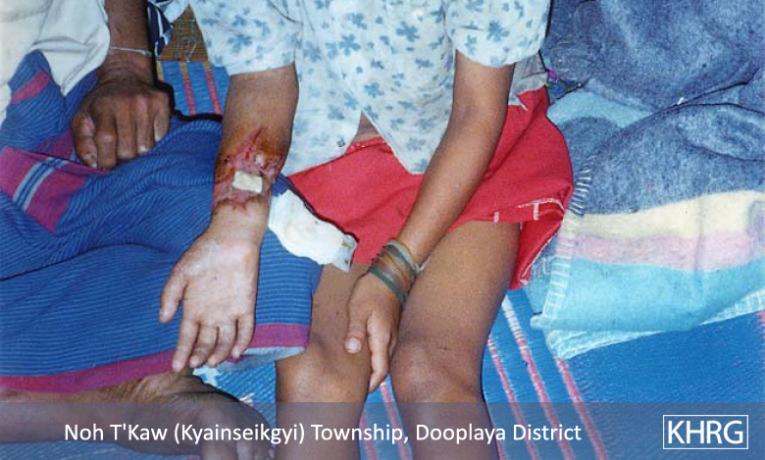

Photos # 5-67, 5-68, 5-69, 5-70, 5-71, 5-72: These photos follow on from photos D4 through D7 in KHRG Photo Set 2002A . After being ordered to relocate along with other villages in Kya In township of Dooplaya district in April 2002, a group of villagers from Tee Law Bler tried to flee to Thailand. On April 28 th 2002 soldiers of SPDC IB #78, Battalion Commander Myo Htun Hlaing commanding, found them sleeping in farmfield huts not far from their village, surrounded the huts and opened fire, killing ten and wounding nine more. Six of those killed were children, four of them under the age of ten. All of those who survived the incident later arrived at Noh Po refugee camp in Thailand. Photo 5-67 shows U K---, 44, with his two surviving children, nine-year-old Saw N--- (left) and twelve-year-old Naw K--- (right). Photos 5-68 and 5-69 show the injuries to Saw N---'s arm from the shooting. The bullet penetrated his upper arm, shattering the bone. Photos 5-71 , 5-72 , and 5-70 show Naw K---'s wounds to her right forearm, and the homemade splint she was using. Their father told KHRG researchers: "We fled before the Burmese [soldiers] arrived. I fled with my wife and children to our field hut. We planned to go to Noh Po [refugee camp] in the morning, but before we could, they came and attacked us in the night time. It was about 10:00 or 12:00 [o'clock] when they attacked us. They shot at my hut and my brother's hut. They continued shooting for about five or six minutes. ... Three people in my family died and two were wounded. My wife was wounded but died 12 days later. Ten days after she was wounded she gave birth [the baby did not survive], but two days she later also died. ... I don't know why they wouldn't allow us to leave [to the refugee camp]. Maybe they thought that we would leave our children in Noh Po and would go back to fight them. I think that they are afraid that other people and other countries would learn about them so they didn't allow us to leave." His wife Naw Pee Lee is shown in photos D5 and D6 in KHRG Photo Set 2002A . [Photos: KHRG researcher]