In a span of just four days at the end of March 2010, two civilians from Wo--- village were injured by landmines while engaging in regular livelihoods activities outside their village in southern Toungoo District. In both cases, fellow community members assisted the injured villagers, carrying them to the nearest medical facility, nearly two hours away on foot. These incidents illustrate the risks mines pose to communities and local livelihoods in southern Toungoo. Local villagers believe risks from the continued deployment of landmines around their villagers, agricultural projects and other areas essential to civilian livelihoods are exacerbated by lack of access to information about mined areas.

On March 26th 2010 Naw Le---, a 40-year-old villager from Wo--- village, Tantabin Township, accompanied nine other women from her village on an early morning trip to collect firewood. At 6:30 am the group walked to a forested hill between Ca--- and Se--- villages, below a State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) Army camp and near a vehicle road. They planned to cut and carry several loads of wood to the roadside and then hire a motorcycle to transport the wood back to Wo--- village. After each carrying two loads of firewood to the roadside, the women decided that they would make a third trip into the forest and then return to the village to cook. At approximately 7:30 am, as Naw Le--- was bringing a final load of wood to the roadside, she stepped on a landmine severely injuring her right leg. Another villager who was nearby rushed to help her while two others, who had been walking a short distance behind her, did not dare to proceed any further down the hill.

The other members of the group helped to carry Naw Le--- back to the village, passing the local SPDC Army camp on the way. The villagers suspected that the landmine had been planted by soldiers from SPDC Light Infantry Battalion #427 who were occupying the camp at the time; when none of the soldiers came out of the camp to investigate Naw Le---’s injury, villagers say that one of the women shouted up to the camp, “You planted a landmine and this villager has been injured. Why aren’t you coming to look?” One of the LIB #427 soldiers then came out from the camp and told the villagers that the landmine had not been planted by the SPDC, but by the Karen National Liberation Army.[1] While villagers told KHRG that they did not believe this assessment, they did not dare to challenge the soldier’s statement; shortly afterwards, an SPDC medic administered three injections to Naw Le--- for her injuries.

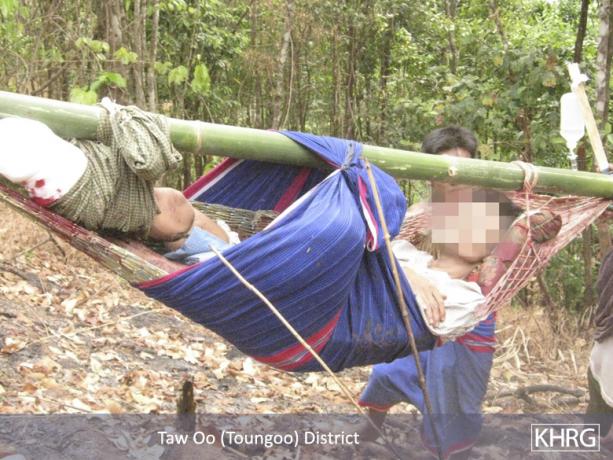

Some residents of Wo--- then carried Naw Le--- to receive medical treatment at Ba---, using a hammock slung from a bamboo pole as a stretcher because no vehicles were available to make the twenty-minute drive. According to local residents, the trip took two hours. Naw Le--- received medical attention for her injuries at Ba--- before being sent to another facility in Ni--- for further treatment. Naw Le--- is the fifth of seven siblings; prior to this incident, she supported herself and her widowed elderly father by cultivating hill fields.

Just three days later, on the morning of March 29th 2010, Saw Pu---, a 46-year-old resident of Wo--- village, went to work at his betelnut plantation near A--- village, accompanied by his wife and their son. At approximately 1:40 pm as Saw Pu--- was returning home, he stepped on a landmine that had been placed near Jo--- village, severely injuring his right leg. Jo--- village is located approximately halfway between Saw Pu---‘s plantation and Wo--- village, and next to a vehicle road. Other residents of Wo--- assisted Saw Pu---, first covering his wounded leg then building a stretcher to carry him to Ba--- to receive medical attention, a two-hour walk from the village. Saw Pu---’s relatives then made arrangements to send him to Ni--- for further treatment. Prior to this incident, Saw Pu--- cultivated hill fields and his betelnut plantation to provide for his wife and their son; he also has four children by his deceased first wife.

Residents of Wo--- believe that the landmines that injured Naw Le--- and Saw Pu--- were planted by SPDC soldiers from LIB #427, which had been stationed in Wo--- and other villages in the surrounding area since early 2010. Between December and January 2010, SPDC troops from battalions under the control of Military Operation Command (MOC)[2] #7 were rotated to replace MOC #5, which had operated in Toungoo since early 2007. MOC #7 has subsequently maintained a key camp just east of Wo--- village. In March 2010, troops from LIB #427 were conducting patrols and offensive operations – including shooting villagers and burning food stores – in the area around Wo---, and were active at other locations along the Gklay Soh Kee to Buh Hsa Kee road in Tantabin Township; according to a KHRG field researcher, LIB #427 was occupying the camp at Wo--- when the landmine incidents occurred.[3]

According to villagers, LIB #427 had been planting landmines carelessly around the village since it arrived in the area, and villagers had not been informed about the locations of landmines.[4] The high landmine contamination of areas used for civilian livelihoods activities around Wo---, and the associated risks for villagers, was further illustrated in another incident on March 27th, just one day after Naw Le--- was injured. At approximately 6:30 am a pig belonging to Naw Ha---, another resident of Wo--- village, stepped on a landmine that had been placed near a school located between Wo--- and the nearby SPDC camp. Local residents believe that this mine, too, was laid by SPDC Army troops because soldiers from LIB #427 reportedly became angry and swore when they saw that the pig had triggered the mine.

Local sources have attributed recent injuries from landmines around Wo--- village to the absence of a relationship between LIB #427 and the community, stating that the soldiers had not attempted to develop a relationship with either the villages or the village leaders in the area. The headman of Wo--- village, for example, did not know the name of the local commander of LIB #427 even though the camp was located just a few minutes' walk east of the village and had been occupied for nearly three months. [5] While SPDC Army soldiers placing landmines in other locations have not typically warned communities of dangerous mine-contaminated areas, villagers in other contexts have highlighted the importance of establishing relationships with armed groups as a method for mitigating risks such as those posed by landmines. In this case, while it is not likely that a better relationship between Wo---village leaders and LIB #427 would have led to complete disclosure of information about particular minded areas, such a relationship might have enabled community leaders to obtain basic information or attempt to influence the types of areas mined by SPDC Army soldiers. In the absence of such engagement, however, civilians and civilian livelihoods in Wo--- village will likely continue to face risks from unmarked landmines.[6]

Footnotes:

[1] Both the SPDC and KNLA have made extensive use of mines in Toungoo and other districts of locally defined Karen State. For recent information on the risk posed by the use of landmines by both parties in nearby Papun District, see Self-protection under strain: targeting of civilians and local responses in northern Karen State, KHRG, August 2010. Villagers also remain at risk from landmines placed by soldiers from KNLA 2nd Brigade active in Toungoo District. Information on the use of landmines in Toungoo by SPDC as well as KNLA forces, including a reported upsurge in landmine deployment by SPDC Army units in 2006, is available in: One Year On: Continuing abuses in Toungoo District, KHRG, November 2006, pp.32-35. For previous documentation dating back to 1999 of heavy landmine use by SPDC and KNLA forces in Southern Toungoo, and the impact on local communities, see especially: Peace Villages and Hiding Villages: Roads, Relocation, and the Campaign for Control of Toungoo District, KHRG, October 2000; Enduring Hunger and Repression: Food Scarcity, Internal Displacement and the Continued Use of Forced Labour in Toungoo District, KHRG, September 2004, pp.87-93, which identified several heavily mine-contaminated areas in Tantabin Township; and “Toungoo District: The civilian response to human rights violations,” KHRG, August 2006, which noted that in early 2006 at least five villagers were injured by landmines in Gkaw Thay Der village tract, Tantabin Township, while being forced to clear brush along the Kler La to Buh Hsa Kee and Kler La to Mawchi vehicle roads.

[2] A Military Operations Command (MOC) typically consists of ten battalions. Most MOCs have three Tactical Operations Commands (TOCs), made up of three battalions each.

[3] See: “Forced Labour, Movement and Trade Restrictions in Toungoo District,” KHRG, March 2010.

[4] SPDC Army forces in southern Toungoo lay landmines to enforce movement restrictions (see: “Forced Labour, Movement and Trade Restrictions in Toungoo District,” KHRG, March 2010); to prevent civilians from returning to live or collect food and essential items in villages in upland areas abandoned to avoid attacks by SPDC patrols (see: One Year On: Continuing Abuses in Toungoo District, KHRG, November 2006, pp.32-35); and to defend against attacks by soldiers from KNLA 2nd Brigade, which conducts operations in southern Toungoo, including laying landmines and launching guerrilla-style attacks on SPDC targets, particularly on SPDC ration deliveries and troop movements along vehicle roads.

[5] It is not clear, however, whether this lack of familiarity between LIB #427 and local villagers is the result of frequent troop rotations in 2010 or an active decision by MOC #7.

[6] Lack of information about dangerous mined areas limits villagers’ ability to move freely and securely, which can be particularly damaging to local livelihoods in southern Toungoo. The soil and upland terrain in this region do not support sufficient rice production and the majority of villagers are therefore dependent on producing crops that can be transported to markets and traded to acquire rice and other essential items. Villagers work year-round cultivating hill fields and different plantation crops according to the season; villagers’ agricultural projects can be located anywhere from a few minutes’ to a few hours’ walk from their homes. For further information on agricultural cycles, rural livelihoods strategies, and the subsequent consequences of local military operations, see: “Forced Labour, Movement and Trade Restrictions in Toungoo District,” KHRG, March 2010; and: “Attacks on cardamom plantations, detention and forced labour in Toungoo District,” KHRG, May 2010.