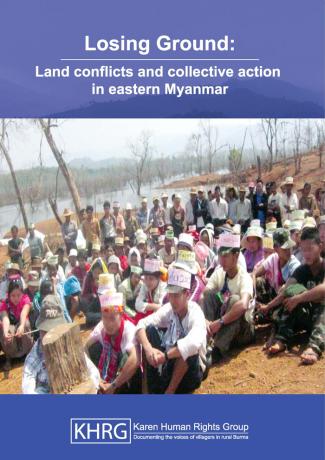

This photo was taken on March 12th 2012 and shows over 400 villagers from Shweygin and Kyauk Kyi Townships protesting the Shweygin Dam in Nyaunglebin District/ Eastern Bago Region. The community member who took this photo told KHRG that villagers chanted three requests of the Government in Burmese: "No continuation of the dam construction. Compensation for lost farmland flooded by the dam. Let the water flow naturally."[6] [Photo: KHRG]

"The two [Tatmadaw] battalions built their camps and confiscated all T--- villagers' lands. Not only T--- villagers, M---, W--- and N--- as well. They didn't confiscate the land systematically in the past. We did farming and could pay them a percentage. In 2012, they will completely confiscate the land. They asked us to sign it away. We don't want to sign and we are against them. They said it belongs to them. It belongs to the State. T--- villagers have no rights."

Saw N--- (male, 60), T--- village, T'Nay Hsah Township, Hpa-an District/ Central Kayin State (Interviewed in June 2012)[1]

"I want to say that our minds shouldn't change because of a company that came and mined for gold. Maybe the company tricked us into selling a lot of our land and orchards by telling us about a dam to make us afraid. They said that they will build the dam and, villagers who have their land close by became afraid, and they wanted to sell all of their properties and go to mine gold. … If the citizens really try to stand stable in their place, I think they can. If they are in fear, if there are a lot of soldiers confronting them, they won't have enough energy to protest."

Saw Th--- (male, 26), B--- village, Dweh Loh Township, Papun District/ North Kayin State (Interviewed in April 2011)[2]

Throughout 2012, villagers in eastern Myanmar described land confiscation and forced displacement occurring without consultation, compensation, or, often, notification. Such displacements have taken place most frequently around natural resource extraction, industry and development projects. These include hydropower dam construction, infrastructure development, logging, mining and plantation agriculture projects that are undertaken or facilitated by various civil and military state authorities, foreign and domestic companies and armed ethnic groups. Villagers consistently report that their perspectives are excluded from the planning and implementation of these projects, which often provide little or no benefit to the local community or result in substantial, often irreversible, harm.

Business and development projects have increased substantially in the wake of Myanmar government reforms and the ceasefire signed with the Karen National Union (KNU).[3] While the cessation of armed conflict has made the area more accessible to investment and commercial interests, eastern Myanmar remains a highly militarised environment.[4] In this context, where abundant resources provide lucrative opportunities for many, and a culture of coercion and impunity is entrenched after decades of war, villagers understand that demand for land carries an implicit threat.

Displacement and barriers to land access arising from these projects present major challenges at the local level. Where land is forcibly taken, fenced-in, flooded, polluted, planted or built upon, the obstacles to effective local-level response are often insurmountable. Even where villagers manage to overcome barriers to organising a response, current legislation does not provide any easily accessible mechanism to allow their complaints to be heard.

Despite this, villagers employ forms of collective action that provide viable avenues to gain representation, compensation and to forestall expropriation. Villagers' ability to navigate local power dynamics and negotiate for unofficial remedies, championed in some cases by an increasingly active domestic media, is forging new and promising avenues for collective action and association.[5]

This report draws on villagers' interviews and testimony, as well as other forms of documentation including photographs, film and audio recordings, collected by community members[7] who have been trained by KHRG to report on the local human rights situation. The documentation received has been analysed for cases in which villagers' access to and use of land has been disrupted, highlights trends of abuse, and details obstructions to the formal channels of complaint or redress that villagers face. The report closes by outlining the serious consequences created by such abuses and the lack of meaningful inclusion of villagers in the making of decisions, which affect them so fundamentally.

The objective of this report is to foster a better understanding of the dynamics and impacts of natural resource extraction and development projects on the ground by presenting a substantial and recent dataset of villagers' testimonies in eastern Myanmar. This report aims to broadcast the perspectives of villagers in eastern Myanmar to actors throughout the country and the international community. The complaints recorded in this report are important, and deserve attention, first and foremost because they represent the lived experience of villagers who are being directly affected by the actions of myriad actors in a rapidly changing Myanmar. It is intended to assist all stakeholders, including Myanmar government officials, business actors, potential and current investors, and local and international non-profit organisations, as they work to: (1) acknowledge and avoid the potential for abuse caused directly or in complicity with other actors; (2) further investigate, verify and respond to allegations of abuse; (3) address the obstacles that prevent rural communities from engaging with protective frameworks; and (4) take more effective steps to ensure sustainable, community-driven development that will not destabilize efforts for peace and ethnic inclusion.

,

,  ,

,

The first photo was taken on July 15th 2012 and shows the damage to villagers' homes that resulted from gold mining near the Baw Paw Law River in Papun District. The second photo was taken on August 1st 2012 and shows an active construction site in the Toh Boh area, Tantabin Township, Toungoo District, run by the Shwe Swan In Company. According to villagers in the area, the Toh Boh Dam operations, including the construction of large buildings to house hydropower generators in Toh Boh village, have resulted in the displacement of villagers. The third photo was taken on August 9th 2012 and shows the flooding of villagers' homes in Let Kauk Wa village, Nyaunglebin District. The community member who took these photos reports that the flooding was caused by the Shwegyin Dam. [Photo: KHRG]

"The two [Tatmadaw] battalions built their camps and confiscated all T--- villagers' lands. Not only T--- villagers, M---, W--- and N--- as well. They didn't confiscate the land systematically in the past. We did farming and could pay them a percentage. In 2012, they will completely confiscate the land. They asked us to sign it away. We don't want to sign and we are against them. They said it belongs to them. It belongs to the State. T--- villagers have no rights."

Saw N--- (male, 60), T--- village, T'Nay Hsah Township, Hpa-an District/ Central Kayin State (Interviewed in June 2012)[1]

"I want to say that our minds shouldn't change because of a company that came and mined for gold. Maybe the company tricked us into selling a lot of our land and orchards by telling us about a dam to make us afraid. They said that they will build the dam and, villagers who have their land close by became afraid, and they wanted to sell all of their properties and go to mine gold. … If the citizens really try to stand stable in their place, I think they can. If they are in fear, if there are a lot of soldiers confronting them, they won't have enough energy to protest."

Saw Th--- (male, 26), B--- village, Dweh Loh Township, Papun District/ North Kayin State (Interviewed in April 2011)[2]

Throughout 2012, villagers in eastern Myanmar described land confiscation and forced displacement occurring without consultation, compensation, or, often, notification. Such displacements have taken place most frequently around natural resource extraction, industry and development projects. These include hydropower dam construction, infrastructure development, logging, mining and plantation agriculture projects that are undertaken or facilitated by various civil and military state authorities, foreign and domestic companies and armed ethnic groups. Villagers consistently report that their perspectives are excluded from the planning and implementation of these projects, which often provide little or no benefit to the local community or result in substantial, often irreversible, harm.

Business and development projects have increased substantially in the wake of Myanmar government reforms and the ceasefire signed with the Karen National Union (KNU).[3] While the cessation of armed conflict has made the area more accessible to investment and commercial interests, eastern Myanmar remains a highly militarised environment.[4] In this context, where abundant resources provide lucrative opportunities for many, and a culture of coercion and impunity is entrenched after decades of war, villagers understand that demand for land carries an implicit threat.

Displacement and barriers to land access arising from these projects present major challenges at the local level. Where land is forcibly taken, fenced-in, flooded, polluted, planted or built upon, the obstacles to effective local-level response are often insurmountable. Even where villagers manage to overcome barriers to organising a response, current legislation does not provide any easily accessible mechanism to allow their complaints to be heard.

Despite this, villagers employ forms of collective action that provide viable avenues to gain representation, compensation and to forestall expropriation. Villagers' ability to navigate local power dynamics and negotiate for unofficial remedies, championed in some cases by an increasingly active domestic media, is forging new and promising avenues for collective action and association.[5]

This report draws on villagers' interviews and testimony, as well as other forms of documentation including photographs, film and audio recordings, collected by community members[7] who have been trained by KHRG to report on the local human rights situation. The documentation received has been analysed for cases in which villagers' access to and use of land has been disrupted, highlights trends of abuse, and details obstructions to the formal channels of complaint or redress that villagers face. The report closes by outlining the serious consequences created by such abuses and the lack of meaningful inclusion of villagers in the making of decisions, which affect them so fundamentally.

The objective of this report is to foster a better understanding of the dynamics and impacts of natural resource extraction and development projects on the ground by presenting a substantial and recent dataset of villagers' testimonies in eastern Myanmar. This report aims to broadcast the perspectives of villagers in eastern Myanmar to actors throughout the country and the international community. The complaints recorded in this report are important, and deserve attention, first and foremost because they represent the lived experience of villagers who are being directly affected by the actions of myriad actors in a rapidly changing Myanmar. It is intended to assist all stakeholders, including Myanmar government officials, business actors, potential and current investors, and local and international non-profit organisations, as they work to: (1) acknowledge and avoid the potential for abuse caused directly or in complicity with other actors; (2) further investigate, verify and respond to allegations of abuse; (3) address the obstacles that prevent rural communities from engaging with protective frameworks; and (4) take more effective steps to ensure sustainable, community-driven development that will not destabilize efforts for peace and ethnic inclusion.