This photo shows a woman named Naw Wah Nay Htoo 38 years old a villager from Hpa-an Township Thaton District who was interviewed about the rape case she suffered. She was raped by a soldier of SLORC in November 1992 when her husband was away from home while her children were fallen asleep. [Photo: KHRG][170]

Foundation of Fear: 25 years of villagers’ voices from southeast Myanmar

Written and published by Karen Human Rights Group KHRG #2017-01, October 2017

“There’s nothing we can do – there’s always a soldier there, pointing a gun at us.”

Female villager quoted in a report written by KHRG researcher, Hpa-an, Thaton, Nyaunglebin districts/Kayin State (published in February 1993)[1]

“We need safety. We also need social organisations for local development [and to provide self- defence training] so that the villagers can be safe from danger.”

Naw Az--- (female) Kyainseikgyi Township, Dooplaya District/ southern Kayin State (Interview received in January 2016)[2]

Keyfindings

1. Since the preliminary ceasefire, the use of extra judicial killings and torture by armed groups, most commonly Tatmadaw, has decreased. However, violent threats continue to be

used to advance the interests of armed groups, as well as the Myanmar government and private companies. These threats are frequently of a serious and violent nature, which

means that community members are often fearful of retaliation if they report the abuse, which deprives them of justice.

2.Over 25 years of KHRG reporting, villagers’ reports of GBV have not declined. Women continue to report feeling insecure in their own communities, which is inpart because of the use

of GBV as amilitary tactic during the conflict, as well as the ongoing violence perpetrated by other community members. Women also report a lack of justice, as frequently the abuse is

not investigatedfully or the perpetrat or is not given an appropriate punishment.

3. Torture continues to be used as ameans of punishment and interrogation by some members of the Myanmar police and armed groups, which has led to reports of miscarriages

of justice and acriminal is ation of villagers by the judicial system.

4.Extrajudicial killings by armed actors have decreased since the preliminary ceasefire; however, the legacy of these killings means that villagers continue to feel unsafe in the presence

oftheTatmadaw.

5.The weak implementation of the rule of law and lack of access to justice results incases of violent abuse remaining unpunished, with victims remaining without justice or closure.The

systematic violent abuses committed by armed actors against civilians during the conflict remain unpunished.

This chapter will examine the extent of the violent abuse that community members from southeast Myanmar have suffered from armed groups, mainly Tatmadaw,[3] during the 25 years KHRG has been reporting. The focus of the chapter will be on the current state of violent abuse in southeast Myanmar, however, due to the lasting impact that extreme violence can have, it is vital to consider the extent of violent abuse perpetrated by armed actors during the period of the conflict covered by KHRG’s reporting period, from 1992 to 2012, and the lasting effect that this has had on villagers’ relationship with the Tatmadaw and the Myanmar government during the current ceasefire period. Throughout the analysis of KHRG’s human rights reports four common types of violent abuse have been identified, which are violent threats, gender-based violence (GBV), torture and extrajudicial killing. These were chosen after careful analyses of the voices of the villagers, what they have previously reported and still continue to report are the main issues. Although these are being discussed in isolation, the reality is that the violent abuse in southeast Myanmar has been so prolific that they all overlap with a wide range of other abuses, including militarisation, displacement and livelihood impacts.

This chapter examines reports spanning 25 years covering the four common types of violent abuse in detail, before proceeding to analyse the impacts of these abuses according to villagers, including fear, physical consequences and livelihood consequences, and the agency strategies that villagers employ when they have faced violent abuse. Two case studies, one from 1999 concerning GBV and one from 2015 regarding violent threats, are presented at the end of the chapter.

When KHRG began reporting on the violent human rights abuses in southeast Myanmar the level of violence that was reported was extreme and the vast majority was perpetrated by the Tatmadaw. While the scope of KHRG reports is only the past 25 years, these violent abuses have been ongoing since the beginning of the conflict against Karen people in 1948 and have been part of Myanmar military tactics in combination with other systematic abuses throughout this time. An example of this brutality and lawlessness stretching back decades, before KHRG reports, was in December 1948 when at least 80 Karen Christians are said to have been massacred by the Tatmadaw, when Tatmadaw threw hand grenades into a church in Palaw in Mergui-Tavoy District (Tanintharyi Region).[4] Attacks have been reported on villagers in non-conflict zones across KHRG’s research areas, and include the systematic and repeated rape of women, the interrogation and torture of groups of Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA) suspects, and widespread cases of indiscriminate killings. Crucially, these abuses have not been collateral damage as part of a larger conflict, but deliberate military tactics by Tatmadaw against civilians.

While KHRG reports document that the vast majority of the abuses came from the Myanmar government military and their related authorities, the Tatmadaw has not been the only group perpetrating violent abuse throughout the conflict period, beginning in 1948, or who continue to violently abuse villagers since the preliminary ceasefire in January 2012. Since their formation in 1994, the non-state armed actor, Democratic Karen Buddhist Army (DKBA Buddhist), has attacked community members in southeast Myanmar, which included physically attacking refugee camps along the Thai-Myanmar border.[5] In 2010, when parts of the DKBA (Buddhist) agreed to a ceasefire and to transform into battalions in Border Guard Forces (BGF) under the command of Tatmadaw, the newly created BGF began perpetrating violent abuse. Democratic Karen Benevolent Army (DKBA Benevolent), formed from DKBA (Buddhist) soldiers who did not agree to integrate into the BGF in 2010, is also responsible for violent abuses and additional deliberate impacts on civilians after 2010, as they attacked both villagers and other armed groups.[6] Since the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA) of October 2015, villagers have also reported individuals from the KNU/KNLA sporadically inciting violence against them. Additionally, in the ceasefire period, violent abuse has been perpetrated by other groups, including the KNU/KNLA Peace Council (KNU/KNLA-PC), Karen People’s Party (KPP),[7] Karen National Defence Organisation (KNDO),[8] Democratic Karen Buddhist Army (DKBA Buddhist splinter),[9] Myanmar Police,[10] local administrative leaders[11] and fellow community members.[12] Overall, the extensive systematic violent abuse against Karen civilians, committed by the Tatmadaw prior to 2012, means that the gravity of these abuses remain hard to overcome, and this has been worsened by the ongoing violent abuse of these additional actors.

There has been a decrease in extrajudicial killings and torture since the 2012 preliminary ceasefire, in which the Myanmar government and KNU committed to ending armed conflict and to work towards implementing a nationwide ceasefire.[13] This was further developed in the NCA, when the KNU, DKBA (Buddhist), KNU/KNLA-PC and the Tatmadaw/BGF[14] agreed to protect civilians from armed conflict. Nevertheless, although examples of killing and torture by armed actors, specifically Tatmadaw, have decreased, the effects of the violent abuse committed in the past by Tatmadaw continue for many villagers, and civilians’ fear and a lack of trust of Tatmadaw remains. Furthermore, examples of violent threats and GBV have remained constant, demonstrating that violent abuse is still an ongoing issue in southeast Myanmar.

In this chapter violent abuse has been separated into four types, however, taken as a whole, violent abuse has had and continues to have a wide and serious impact on Karen communities across southeast Myanmar. Due to the wider impacts that violent abuse can have, such as creating terror and undermining community and family cohesion, there are domestic and international legislation covering these issues.

In both the 2008 Myanmar Constitution and the Myanmar Penal Code there are articles protecting the fundamental rights of civilians.[15] Although the Myanmar Penal Code covers all activities during the conflict,[16] Tatmadaw had de facto impunity from these laws. Importantly for this chapter, Tatmadaw impunity became formally enshrined in law in the 2008 Myanmar Constitution, as Article 445 states:

“No proceeding shall be instituted against the said [previously-ruling] Councils or any member thereofor any member of the Government, inrespect of any act done in the execution of their respective duties.”[17]

The ongoing violent abuse by many of the armed actors in southeast Myanmar highlights that Myanmar’s penal code and constitutional commitments are not being upheld. Therefore, the Tatmadaw is not the only armed actor that acts with impunity, the only difference being that impunity has not been formally enshrined for the other military groups.

Although the Tatmadaw has impunity from domestic legislation, they did sign the NCA and are bound by its agreements. Also bound by these agreements are the KNU, DKBA (Benevolent) and KNU/KNLA-PC, as well as the BGF as they are considered under the Tatmadaw army. Specifically, the NCA stipulates that civilians, which includes community members across southeast Myanmar, need to be protected against the violent abuses discussed in this chapter.[18] Therefore, where the signatories of the NCA are shown to undertake acts of violent abuse they can be seen to be violating the ceasefire agreement. However, it must be noted that the word ‘avoid’ is used at the beginning of each stipulation, and suggests that some incidences of these violent abuses could be allowed to continue so long as they are not excessive.[19]

Evidently, domestic legislation and the NCA are not able to prevent impunity, especially for the Tatmadaw, but where domestic laws have failed international legislation may be able to provide some guidance. The Fourth Geneva Convention is the most relevant document for this chapter, as it outlines the types of violent abuse that non-combatants should be free from during conflict.[20] Throughout this chapter, it is clear that many of the abuses committed by the Tatmadaw have been in direct violation of the Fourth Geneva Convention.[21] While formal legislation can help to guide discussion of human rights abuses in southeast Myanmar across the 25 years of KHRG reporting, the real understanding of violent abuse can only come from listening and understanding the lived experiences of the villagers.

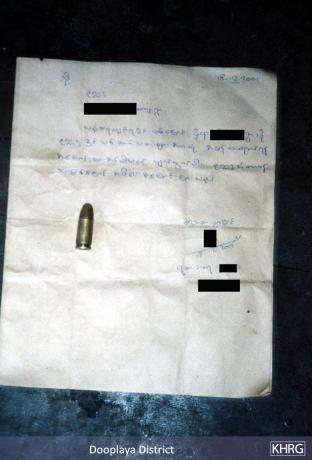

In contrast to other forms of violent abuse, threats made by armed actors, particularly Tatmadaw,[22] have been reported consistently by villagers over the 25 years of KHRG reporting.[23] During the conflict, threats by armed actors, most commonly Tatmadaw, but to a lesser extent DKBA (Buddhist) and BGF (from 2010), were issued to force community members to fulfil other abuses, such as forced relocation or forced labour. Tatmadaw and ethnic armed groups (EAGs) intimidated villagers using an alarming variety of methods, including threatening death, burning villages, torturing and looting.[24] The ongoing nature of villagers’ reports shows that these threats have been and still are used to enforce other abuses against Karen civilians. The method of threatening civilians can vary, as some threats in past reports were given verbally,[25] some were by physical threats such as by shooting in the direction of a person,[26] or some were in writing, most notably in the form of order letters.[27] Often these threats were followed by actual acts of violence and other abuses. In comparison, since the 2012 preliminary ceasefire, there has been a continuation in the use of threats as a form of intimidation by armed actors, while the subsequent violent acts have decreased. Due to the legacy of the conflict, powerful armed actor’s use of these threats continues to impact Karen civilians through intimidation, fear, coercing villagers, and attempting to undermine villagers’ agency in avoiding or counteracting abuse.

Since the preliminary ceasefire, threats have commonly involved private companies[28] and government officials,[29] usually in collaboration with armed actors, who seek to limit the agency and autonomy of villagers by preventing them from resisting land confiscation[30] and using threats to advance their business interests.[31] There are a variety of intimidation tactics that have been utilised to achieve these aims, for example the BGF shelled in the direction of one village,[32] government officials verbally threatened to sue villagers[33] and the Karen Peace Force (KPF)[34] and BGF threatened to imprison villagers if they complained about land confiscation.[35] In one case, the Tatmadaw stated that they would only give the villagers compensation for the land that was confiscated if the villagers agreed to sign over their lands to them, and moreover they would force them to do the additional abuse of forced portering if they refused to sign:

“They [Tatmadaw] threatened [the villagers] like, if they did not sign, they would include them in porter [service].They also said,‘If you do not sign, we will not give you compensation.’”

Naw A--- (female, 44), Hlaingbwe Township, Hpa-an District/ central Kayin State (interviewed in June 2015)[36]

While, there are examples of threats connected to development projects preceding the preliminary ceasefire,[37] most of the examples of threats show that they were a military tactic by Tatmadaw and, at times, DKBA (Buddhist) and BGF. This use of threats as a military tactic is in clear violation of the Fourth Geneva Convention, which prohibits the use of intimidation against civilians during conflict.[38] How Tatmadaw and DKBA (Buddhist) frequently issued threats was through message or order letter by both army camp commanders and battalion commanders. Order letters were sent via messenger (conscripted commonly as a form of forced labour) to the village head, with demands for immediate action and threats of consequence if the village head chooses not to adhere to the order.[39] For example, in 2006 the Tatmadaw ordered, in a series of letters, villagers living east of the Day Loh River, Toungoo District, to relocate; those villagers who chose to defy this order were sent chilli, charcoal and a bullet, to signify torture, village burning and death.[40] Despite these threats, villagers and village heads employed negotiation,[41] avoidance[42] or partial compliance to avoid the full severity of potential abuse.[43]

Additional motives for the threatening behaviour of the Tatmadaw, and at times the DKBA (Buddhist), were to limit action or to impose a punishment for something that was outside of the villagers’ control, deeply and deliberately implicating villagers in the consequences of the conflict. For example, in 2008 DKBA (Buddhist) Battalion #907 officers threatened to confiscate all land from AAk---, AAl---, AAm---, AAn---, AAo---, AAp--- and AAq villages, in Dooplaya District, if any DKBA (Buddhist) soldiers stood on a KNLA landmine.[44] The impact of the threats therefore extended to villagers livelihood security and daily sustenance, and were a deliberate attack on their livelihoods.

Not only did intimidation create significant insecurity for villagers, the threats that were issued during the conflict period were often extremely violent, and perpetuated the lawless, oppressive, abusive environment in which they were being made; for example, Naw AAs--- was arrested, tortured and then threatened by DKBA (Buddhist) soldiers, including one called Bo XXXX, in 1997:

“The first time they [DKBA Buddhist] arrested meal one, but the second time they also arrested my relatives P--- and L---[both men]. P--- is 40 years old and L--- is over 30. They beat P--- one time, but not L---.They said that Bo XXXX’s father-in-law died because these two had joined with the Karen soldiers to come and kill him. Bo XXXX told me he would kill 5 people to repay this one life.”

Naw AAs--- (female, 49) quoted in report written by KHRG researcher, Myawaddy Township, Hpa-an District/central Kayin State (published in August 1997)[45]

Whilst the severity of the violence accompanying threats made by powerful armed actors has lessened since the 2012 preliminary ceasefire, threats remain violent and continue to reinforce an environment of insecurity, particularly near armed actors. For example, one KHRG report from October 2014, which details the threats of a BGF Commander in Hpapun District, shows that some armed actors now use threats to increase their impunity, so that they will not be held accountable for other abuses that they have committed:

“He [BGF Commander] went from village to village, as he was worried that the villagers would complain about him and his business would not run smoothly.He showed his cane stick to the villagers and threatened the villagers.”

Situation Update written by a KHRG researcher, Bu Tho Township, Hpapun District / northeastern Kayin State (published in October 2014)[46]

The threats from the conflict period have an ongoing legacy in southeast Myanmar, and considering that the NCA contains no reference to threats by armed actors, there are few obligations preventing the Tatmadaw and other armed actors from continuing to intimidate villagers as they have done throughout the conflict, which can be seen in the sporadic examples of Tatmadaw commanders seeking to oppressively control villagers with threats. For example, in October 2014 a Tatmadaw commander threatened to kill any villagers outside of their homes at night in AAg--- village, AAh--- village and AAi--- village, in Hpapun District.[47] Moreover, the majority of threats are now used as strategies to advance business and development interests, but the fact that these interests are conducted by armed actors indicates that the relationship of power and abuse between armed actors and Karen civilians remains reminiscent of the conflict era.[48] These threats are now preventing villagers from challenging the actions of powerful actors in southeast Myanmar and allow development projects to be implemented with little benefit for villagers.

Throughout 25 years of KHRG reporting, gender-based violence (GBV) has occurred and continues to occur throughout southeast Myanmar in a range of different contexts, places and to a variety of women, with extensive repercussions for women and limited consequences for the perpetrator. Based on KHRG analysis between 1992 and 2012, widespread sexual assault and rape of women by Tatmadaw was ingrained in military tactics of civilian abuse. Since the preliminary ceasefire in 2012, the number of sexual assaults and rapes perpetrated by armed actors has decreased compared to the past, however, these abuses continue, often with impunity, by some armed actors. Furthermore, the culture of impunity that developed during the military era, as well as the lack of comprehensive protections for women in domestic legislation,[49] means that civilians can easily perpetrate acts of GBV as well. Overall, it is unlikely that the full scale of this abuse is represented in the KHRG reports, as it is an abuse that is severely underreported because of a combination of threats and social stigma.[50]

Cases since the preliminary ceasefire demonstrate the insecure and unsafe environment in southeast Myanmar for women, which have remained the same throughout KHRG’s 25 years. For example, a 16 years old girl was raped and murdered by a fellow villager in 2016, when she had been out of the village collecting betel-nut in Dooplaya District.[51] In particular, GBV often appears to be targeted at vulnerable women, as there are reports of attacks on women who have an intellectual disability[52] or are particularly young,[53] or who stay alone. For example, Naw A--- from Kawkareik Township was raped by a perpetrator who knew she would have been alone when he entered her home. According to the victim:

“He just asked how many [people] I lived with and I answered that I lived alone. He never has been to my house. That was the first time that he visited me.”

Naw A--- (female, 45), Ab--- village, Kawkareik Township, Dooplaya District / southern Kayin State (interviewed in July 2015)[54]

In addition, drugs can also play a role in GBV, as there are accounts of perpetrators being under the influence of yaba at the time of assault.[55] However, it must be noted that drugs are not involved in every case of GBV and that the use of drugs neither causes GBV nor absolves the perpetrator of responsibility for their actions.

In comparison to the opportunistic nature of GBV since the preliminary ceasefire, a common theme in reports from the conflict years was that women were deliberately targeted by Tatmadaw soldiers, showing that rape and GBV was used as a “weapon of war”.[56] The activities of the Tatmadaw were in direct violation of international humanitarian and human rights law including: the Geneva Conventions (1949) and Additional Protocols I and II (1977),[57] the Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women (1993),[58] the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW),[59] the Declaration of Commitment to End Sexual Violence in Conflict (2013),[60] and several binding UN Security Council resolutions such as 1325 (2000), 1820 (2008), 1960 (2010), 2106 (2013) and 2122 (2013)[61]. In reports under conflict, villagers often reported that Tatmadaw used GBV as a tactic to degrade the Karen community and undermine support for the KNU and KNLA, because systematic GBV challenged the existing social structure of communities in southeast Myanmar. In an interview from 1997, Naw Ac--- explained the tactics of the Tatmadaw stating that:

“If the Burmese [Tatmadaw] capture them [villagers], they will use them as slaves, rape the mand beat them until they are dead, because that is what the Burmese Army usually does. They kill the children, they make the husband work, they rape the wives and daughters."

Naw Ac--- (female, 27), Ler Mu Lah Township, Mergui-Tavoy District/ Tanintharyi Region (Interviewed in March 1997)[62]

This suggests that the Tatmadaw used GBV with the intent to attack all levels of Karen society, from the youngest to the oldest members, with specific and extensive violent abuses perpetrated against women. The targeting of women through GBV by the Tatmadaw is clear in reports from the conflict, especially while women were completing forced labour.[63] In an interview from 1992, Daw Ad--- explained the systematic violence she suffered by the Tatmadaw because she was a woman:

“All night long the soldiers would come and drag women away to be raped. They took turn sand women were often raped by several soldiers in on enight. I was raped frequently like the others. While I was being raped or trying to sleep I could hear the screams of other women all around. This went on all night, and then in the morning they’d make us carry our loads over mountains again. I felt especially sorry for Naw Ae---, who was being raped very badly every night and was much too small to carry her load.”

Daw Ad--- (female, 32), Kyaikto Township, Thaton District/ northern Mon State (interviewed in January 1992)[64] Rape, including gang rape, of civilian women and girls by Tatmadaw military personnel was a widespread abuse throughout southeast Myanmar, and perpetrated at all levels of the Tatmadaw, from privates to commanders.[65] This explains why the threat of rape was most prevalent where military units were based or when they were temporarily encamped near villages already under Tatmadaw’s control.[66] The structures of power connected to militarisation heightened the villagers’ vulnerability to such abuses, and the widespread use of rape served the military as a tool for intimidation and control of both women and entire communities. This is in contrast to KHRG reports from after the preliminary ceasefire, which shows that GBV has most often been perpetrated by lone individuals. For example, a Tatmadaw soldier attempted to rape a woman in 2013, in Toungoo District, but the case was silenced until he was taken to the local army camp and interrogated.[67] Therefore, although the fear of GBV has not disappeared or lessened for women, the motives, as well as some of the actors, may have changed from a military targeting of Karen society, to individuals attacking women and in doing so undermining the status of women.

Torture is one of the major issues reported by KHRG throughout the 25 years of documenting human rights abuses. One key finding is that both mental and physical torture has been used systematically by all the armed groups in southeast Myanmar.[68] Torture was used excessively by the Tatmadaw, and to a lesser extent the BGF[69] and DKBA (Buddhist),[70] throughout KHRG’s reporting period prior to the 2012 ceasefire. Since the preliminary ceasefire, the Tatmadaw[71] and BGF[72] have continued to be involved in torture of community members, with some cases now reported as involving Karen EAGs, such as the KNLA,[73] KNU/KNLA-PC,[74] KNDO[75] and DKBA (Benevolent).[76] While the rate at which torture committed against Karen civilians by the Tatmadaw has decreased, it is still continuing by armed actors in cases when the villagers are arrested, which indicates that due to the long history of its use during conflict, torture is viewed by many powerful armed actors as a legitimate tool for both interrogation and punishment to the current day.

KHRG has reported widely on the use of torture in southeast Myanmar, and many of the reports from the conflict period can help to explain what torture is and how it is used. KHRG’s definition of torture is primarily informed by villager’s descriptions, as explained by KHRG in 2006, when it was understood as a military tactic in combination with other abuses:

“Villagers live in situations of heightened vulnerability where they are prone to beatings and mistreatment by individual soldiers who may wander into their village to loot, deliver orders or simply loiter. While the torture and mistreatment of villagers may not always stem from specific military orders, suchabuses serve the over all SPDC objective of militarising Karen territory and cultivating a situation where villagers are easily exploited.”

Thematic Report written by KHRG researchers, Kayin State/ southeast Myanmar (published in November 2006)[77]

Since the preliminary ceasefire the use of torture has altered, and the current use of torture throughout southeast Myanmar is more often associated with law and order and the justice system. Villagers indicate that armed actors,[78] the police, and government officials have misused their powers, as often villagers have reported being arbitrarily arrested and tortured without any explanation or evidence for why they were arrested.[79] In these cases torture can be seen to be used as a method of interrogation, as Ma P--- from Thaton Township, Thaton District explained happened to her husband when he was arrested:

“On the second time tha the was arrested, he was beaten, punched, [andthey] hit him [against something], with held water and food from him for three days, [and] they hung him up by his neck when they questioned him. [When they interrogated him] they made him kneel on a wooden plank full of two inch iron nails”

Ma P--- (female, 42), B---Village, Thaton Township, Thaton District/ northern Mon State (interviewed in July 2015)[80]

A consequence of this torture was that Ma P---’s husband confessed to participating in a robbery, which she contended was not true, and suggests that miscarriages of justice have happened to villagers in southeast Myanmar under the weight of such abuse. This is a serious issue and shows that the Myanmar government continues to allow serious human rights abuses to continue in southeast Myanmar,[81] and that the Myanmar government authorities work towards the criminalisation of villagers rather than providing them with protection.

While torture is now more often used as a method of interrogation, during the conflict torture was used to break civilians down mentally and physically, and to force villagers to comply with orders, to provide information[82] or to punish potential KNLA supporters.[83] The main perpetrator of torture during the conflict was the Tatmadaw, with villagers frequently tortured when portering[84] or when detained if they were suspected to have links to the KNLA.[85] A harrowing case comes from an interview with three women who were tortured over a number of days by the Tatmadaw in 1992, which included incidences of burning, beating, waterboarding and mentally torturing a woman by making her dig and lie beside a grave. According to one of the women, innocent villagers were accused of helping the KNLA and then tortured:

“They tied up 8 of us by the hands and took us away outside the village. The officer shot a pistol near our ears and I was very afraid. First the soldiers hung us by our hands with rope, so that our feet weren’t touching the ground. They left us hanging like that for one hour. Then they laid us all on the ground on our backs, tied our hands behind our backs and tied our legs up to the tree branch so they were pointing straight up.”

Villagers quoted in report written by KHRG researcher, Karen State/ southeast Myanmar[86] (published in February 1993)[87]

As can be seen in this example, torture was frequently reported to be extreme and sustained, and furthermore, the torture by the Tatmadaw was often very public. The Tatmadaw used these tactics either because the culture of impunity meant that they did not need to hide their activities or because they wanted to make it public as a way to break the morale of Karen communities, and in this way, undermine civilian support for Karen EAGs. For example, in 1994 Tatmadaw very publically tortured a villager and left him to die:

“On March 3,1994, soldiers from SLORC [Tatmadaw] Infantry Battalion #35 (based in Kyaukkyi) entered Paw Mu Der village. They found photos in Saw Gay’s house showing a man in Karen uniform, so they accused Saw Gay of having a relative in the Karen Army and ordered him to explain. Afterwards they took him in front of the whole population of the village, including his wife and 2 children (aged 4 and 2), and cut off his arms and legs. They left him bleeding on the ground for 2 hours, but he was still not quite dead so they cut off his penis, then cut open his belly and ripped out his internal organs.”

Field Report written by KHRG researcher, Nyaunglebin, Mergui-Tavoy, Hpapun Districts/Kayin State (published in April 1994)[88]

These public displays of torture have ceased since the preliminary ceasefire, but as concerning is that torture is now conducted either at night or in secret by armed actors,[89] as a villager explained happened to him after he was arrested by the KNLA in 2016:

“They [KNLA] grabbed me and put me into the truckand they hit me andpunched me.I told them that there was a village leader who they could talk to and they replied that they [the village leader] do not understand [the situation].”

Saw AAa--- (male, 56), Kyaukgyi Township, Nyaunglebin District/ eastern Bago Region (published in November 2016)[90]

Considering that torture now usually accompanies arbitrary arrest, it is concerning that armed actors, government authorities and the Myanmar police now use torture in a more secretive manner, which means that the level of abuse may be more hidden than what is reported. Therefore, although extreme levels of public violence are rarely seen presently in southeast Myanmar, the sporadic use of torture is a significant failing of the Myanmar government and the KNU, as it is a significant breach of international humanitarian legislation, as well as an infringement of the NCA.

Throughout the 25 years of KHRG reporting, extrajudicial killings have been an ongoing abuse that villagers in southeast Myanmar have been confronted with. During the conflict the vast majority of indiscriminate and extrajudicial killings were perpetrated by the Tatmadaw,[91] with some incidences by the DKBA (Buddhist) and BGF, with the intent to oppress Karen civilians, to punish supporters of the KNU and to create widespread fear. KHRG reports since 2012 indicate that there has been a significant decrease in systematic and large scale extrajudicial killings by armed actors, and the main perpetrator of the recent examples of extrajudicial killings has been the BGF,[92] which suggests that the Tatmadaw is indirectly continuing its violence against community members. Additionally, examples of extrajudicial killings have been committed by the Tatmadaw,[93] KNLA, KNU/KNLA-PC[94] and DKBA (Benevolent).[95] The ceasefire period has seen extrajudicial killings perpetrated by a wider range of actors, but to a much lesser extent. This indicates that use of extrajudicial killings has changed from being a military tactic of targeting the Karen population, to a way of implementing military rules by armed groups or an activity by rogue commanders.

Although there has been a decrease in extrajudicial killing since the preliminary ceasefire, the current risk of villagers being killed by armed actors remains serious, especially by the BGF, who are most frequently reported as carrying out these killings. Examples of killings from Hpa-an District include a refugee shot dead in 2016 by the KNDO for illegally logging,[96] the BGF shooting a villager on sight in 2015[97] and the beating to death of a villager by the BGF after he had had an argument with another villager in 2015.[98] Nevertheless, even though the motives behind the killings have changed, the ongoing incidences of killing of civilians in southeast Myanmar by armed actors indicate that there is impunity of armed actors for these abuses. Furthermore, the extent to which the villagers were targeted during the conflict is still felt in southeast Myanmar, as villagers report that fear in the presence of military, particularly Tatmadaw and BGF, remains.

This fear can be understood through the past KHRG reports, in which villagers reported Tatmadaw’s tactics of extrajudicial killings, including the policy of shooting villagers on sight, and the impact this has on their daily lives. KHRG reports from that time detailed that community members were killed in numerous circumstances and places, as part of the complete oppression of Karen civilians. Examples included, people being shot outside their houses,[99] while farming,[100] in the refugee camps,[101] as forced labourers[102], and during Karen New Year celebrations,[103] to name but a few examples. These highlight that at all stages of a community member's day their lives were at risk. The arbitrary nature with which villagers could be killed by the Tatmadaw, and in later reports the DKBA (Buddhist) and BGF, was highlighted in an interview with a female villager from Hpa-an Township, who recounted the killing of two men in February 1994:

“They [Tatmadaw] arrested and killed two other villagers but nobody saw it, the men just disappeared. One of them was Maung Htun Bwah – they killed him by mistake instead of Maung Htun Oo, who is a Karen soldier. The other was Maung Than Chay. He was just a civilian, and he vouched for Maung Htun Bwah. Then they killed Maung Htun Bwah and took money from him. They thought if they released Maung Than Chay he would cause problems for them by telling people, so they accused him of being on the Karen side and killed him too. Both of them had families.”

Naw Aq--- (female, 48), Hpa-an Township, Thaton District/ northern Mon State (published in May 1994)[104]

What is evident in this example is that the motives behind the killings were based upon weak accusations, mistaken identity and rumours, showing that all villagers were vulnerable and suspect to Tatmadaw accusations. Contrastingly, armed groups who commit extrajudicial killings since the preliminary ceasefire are likely to have more specific and targeted motives, such as killing to confiscate land or demonstrate their power against certain individuals.

One particular violent period of killing during the conflict was between 1998 and 2000, when the Tatmadaw used death squads, known locally as Sa Thon Lon,[105] to deliberately target any Karen civilians who had ever had a connection to the KNU/KNLA, rumoured or factual, big or small.[106] Villager Saw Ar--- from Mone Township suggested that the Sa Thon Lon was part of a wider plan to attack the KNLA by targeting civilians in 1999:

“They are the Sa Thon Lon. People said that they don’t ask any questions [they kill without interrogation] and they are going to “cut off the topsofall the plants”. The second group, Sweeper, will come to sweep up the people and then the third group will come to scorch the earth and “dig out the roots”. They will kill all there latives of the forest people [the KNLA].”

Saw Ar--- (male), quoted in report written by a KHRG researcher, Nyaunglebin District/eastern Bago Region (published in May 1999)[107]

The description of the Sa Thon Lon indicates that the Tatmadaw had little or no value for the lives of villagers living in southeast Myanmar, explicitly and brutally targeting civilians as a way to undermine the network of Karen communities and their support for the KNLA.[108] During the conflict period, which saw many villagers choosing to strategically displace themselves to avoid such violent abuse, KHRG reported the brutal nature with which the Tatmadaw deliberately attacked villagers over decades, including an incident from 2007 when a 19 year old man was stabbed in the eyes and mouth in Toungoo District[109] and another from 1995 when a villager was beaten, tied up and then stabbed to death in Dooplaya District.[110] Although extrajudicial killing cases span the 25 years of KHRG reporting, these abuses still resonate today because of theiseriousness. These widespread extrajudicial killings are hard to forget, and past abuses need to be addressed in the ongoing peace process in order to start to provide villagers with some form of closure.

Although there has been fewer reports of extrajudicial killings since the preliminary ceasefire, there are still incidences of villagers being killed without warning and for minor reasons, giving further reason for Karen villagers to strongly reject the militarisation of their areas. One example of the ongoing abuse comes from a KHRG Incident Report detailing how Saw A---, from B--- village, was fishing when ‘hewasdirectlyshotbytheBGFunexpectedly’in March 2015. He was then shot twice more and taken to hospital by fellow community members where he died from his injuries. It is noted in the KHRG incident report that the BGF had not implemented any rules for the villagers to follow at the time of the killing, but they have since stated that:

“We created the rule in our area that we are not allowed [to let] any villagers go out of the village after 6 pm and until 6 am.”

Incident report written by a KHRG researcher, Bu Tho Township, Hpapun District/northeastern Kayin State (published in September 2015)[111]

The killing of Saw A---, based on arbitrary and ill-defined military rules, had a significant impact on the lives of his family, as his widow was left with six children to look after. According to the KHRG Incident Report, Saw A---’s wife, Naw C---, went to the BGF Commander to demand compensation, but this was not paid, despite the Commander giving his agreement. The killing of Saw A--- is a strong example of the risks that the villagers still face in southeast Myanmar from armed groups. It shows the impunity with which the armed groups act, which is informed by the foundation of impunity for Tatmadaw during the conflict; as well as the lack of justice given to villagers by Myanmar authorities. Therefore, in addition to the need to address the past abuses in the peace process, the ongoing impunity and killings need to come to an end to ensure that there is security and justice for villagers in southeast Myanmar.

Violent abuse in southeast Myanmar has been perpetrated in a variety of ways, all having similar consequences for villagers. Most notably, threats, GBV, torture and extrajudicial killings help to create an atmosphere of fear of armed actors, most commonly Tatmadaw and BGF, within communities, as well as physical health problems for villagers. Moreover, these physical problems, in combination with the threats, extrajudicial killings, and other violent abuses have had serious impacts on villagers’ abilities to maintain their livelihood and have led to the breakdown of families and communities across southeast Myanmar.

Violent abuse has created an atmosphere of fear within communities, especially an ongoing fear of the Tatmadaw[112] and related Myanmar government authorities. This is a significant barrier now to the acceptability of Myanmar government intervention in southeast Myanmar, the presence of armed actors in Karen and near Karen communities, and the legitimacy of the peace process and political process as a whole as viewed by Karen communities.

Fear of the Tatmadaw is very clear in the reports from the conflict period, which described how villagers fled from their homes if they knew they were approaching, and then being fired upon when fleeing. The fear that the Tatmadaw struck in people was articulated by a villager from eastern Hpa-an District in 1997:

“Nobody had guns or was wearing uniforms – we were all only civilians. The Tatmadaw soldiers just saw people running and shot them. They knew for sure that they were villagers, they shouted “Don’t run!”, but the villagers were afraid of them and ran and they shot at them. Three of them were running through the field, and two of them were hit. Pa Kyi Kheh was hit in the middle of his back. He was hit twice. My younger brother P--- was also wounded. The people who didn’t run saw their friends get shot, so they ran too and then they were also shot at by the soldiers. The Burmese say if we run they will shoot - so they did shoot.”

Villager quoted in a Commentary written by KHRG researcher, Hpa-an District, central Kayin State

(published in September 1997)[113]

Compounding this fear was the consequence that if caught by the Tatmadaw villagers would be subjected to forced labour[114] and forced recruitment, as well as being tortured,[115] shot on sight,[116] or raped.[117] The fear of forced labour was commonly reported by villagers as it often led to them experiencing extreme violence, with reports of villagers being shot when they could no longer carry supplies[118] and being left to die from weakness or illnesses that they had caught.[119] Therefore, villagers chose to flee from the Tatmadaw because interaction with them more likely than not led to the villagers suffering violently. Of relevance, no steps have been taken by the Myanmar government or Tatmadaw to address these abuses, or the ingrained fear of the perpetrators, which villagers retain to the present day.

In particular, the ingrained fear of the Tatmadaw is frequently voiced by women, who have significant concerns about their safety because of the past and present cases of GBV. There are recent examples of women feeling unsafe in the presence of Tatmadaw soldiers, as noted in one interview with a female villager from Kyainseikgyi Township, Dooplaya District, in 2016:

“They [Tatmadaw] are male and also have weapons in their hands. We are afraid of them when we travel [do not feel secure when going between places] because we are women. As you know, in the past they killed and raped villagers as they wanted.”

Naw Af--- (female), Kyainseikgyi Township, Dooplaya District/ southern Kayin Sate (interview received in January 2016)[120]

This fear continues to be echoed by female villagers who have reported that they do not feel safe with Tatmadaw and BGF soldiers living nearby and patrolling their area,[121] for reasons including that the young soldiers are often unmarried, the soldiers make lewd remarks at female villagers,[122] and the abuse of rape against ethnic women by Tatmadaw soldiers during the conflict, which remains silenced to this day, without justice.[123] In evidence of their safety concerns, women and other villagers in recent KHRG reports state that they continue to limit their travels at night in order to stay safe, particularly around army camps.[124] These safety concerns tie in to the perception that Karen villagers are unsafe near Tatmadaw and BGF army bases, and the common and often repeated request from Karen villagers that the Tatmadaw and BGF demilitarise and withdraw from civilian areas in southeast Myanmar.[125]

The desire of villagers for the withdrawal of Tatmadaw and BGF forces indicate that villagers continue to live under the threat of violence, showing that the context of insecurity, military abuse and infringement of villagers’ rights remains in southeast Myanmar, as one soldier from DKBA (splinter) Na Ma Kya group told a villager in 2015:

“I do not have the right to kill you, but I do have the right to beat you.”

Naw A--- (female, 32), F--- village, Kawkareik Township, Dooplaya District/ southern Kayin State (interviewed in March 2015)[126]

This DKBA (splinter) Na Ma Kya soldier suggests that they have a ‘right’ to act violently, which is in clear violation of domestic and international legislation and has a direct implication on villagers’ ability to trust armed groups. The ability of armed groups to continue to threaten violence indicates that armed actors continue to act with impunity, which exacerbates the fear and mistrust that villagers feel towards the armed groups, especially Tatmadaw and BGF, who remain active in their villages. The fear of the armed groups is an ongoing issue from the conflict, and has often developed out of the lived experience of violent abuse and the physical impact this has had on villagers.

As torture and GBV are both physical attacks on community members, the victims frequently face physical ramifications, which are often long-term and compounded by the lack of healthcare in southeast Myanmar. For example, a female villager from Hpa-an Township reported the health problems she experienced after she had been tortured in 1994:

“On April3 [1994] they [Burmese soldiers] asked me if any Kaw Thoo Lei [KNLA] had entered the village then I said no. And then they just started beating me with a bamboo pole as thick as your wrist. They beat me 3 or 4 times on my ribs. I don’t know, but I was told 2 of them are broken. It hurt a lot. I couldn't even breathe. After that I couldn’t stand up, and I couldn't lay down either. Even now, people have to help me stand up or lay down. There is no hospital here, so I put special water and saffron on it. These men just accuse us, so we have to deny it and then they beat us.”

Female villager quoted in a report written by KHRG researcher, Hpa-an Township, Thaton District/northern Mon State (published in May 1994)[127]

This villager explained that the torture had led to ongoing and long lasting physical problems, which meant that she was unable to return to even a semblance of normality after the abuse. Furthermore, these physical problems that she was left with appear to impact her ability to fend for herself and therefore maintain her livelihood

As with torture, victims of GBV have to cope with serious physical impacts, including pregnancy and abortion. Villagers reported that pregnancy and abortion often occurred after women had been raped while being forced to porter or labour for the Tatmadaw. The serious nature of the abuse during forced labour and portering meant that women experienced sustained GBV, by more than one person and over a significant period of time.[128] Unsafe abortions stemming from rape by the Tatmadaw held serious health risks for the women, as explained by Naw Am--- who was raped when she was taken for forced labour in Thaton District in 1993:

“Then when we got home many of us were pregnant. I was pregnant myself. We all had to get medicine to get rid of the baby. Now I’m in debt 1,000 kyat (US$1.00) for medicine. One of my friends who came back pregnant got rid of the baby too, and she’s been very sick and thin ever since. She’s still very sick.”

Naw Am--- (female, 30) quoted in a report written by KHRG researcher, Hpa-an, Thaton, Nyaunglebin Districts/Kayin State (published in February 1993)[129]

These serious health consequences, in combination with livelihood issues and the social stigma for women returning to their communities and families following rape, ensured that this abuse significantly weakened and damaged Karen communities, as intended by the Tatmadaw. Although the number of reports that KHRG has received about pregnancy following rape is limited, more commonly reported is the physical injuries that come from women being beaten or physically attacked because of their gender. Physical impacts come not only from rape but the accompanying violence, which is often reported occurring when victims or their family members try to report cases of GBV.[130] Therefore, the physical effects of GBV are exacerbated by inadequate healthcare, as well as the lack of suitable justice in southeast Myanmar. These physical injuries not only impact the victims themselves, but help to exacerbate additional consequences, most commonly the sustainability of community members’ livelihoods.

Villagers in southeast Myanmar have frequently reported that violent abuse has left them unable to maintain a sustainable livelihood, which was often because they felt fear and were incapable of working due to physical impairments. Livelihood impacts are rarely restricted to the victim of violent abuse, and community members in KHRG reports have spoken about how the effect of violent abuse by armed groups goes far beyond the immediate victim. Regularly, the impact on the wider family was most significant when villagers were killed by the Tatmadaw, as they left behind family members who often faced financial difficulties because they lost the main income generator for the family.[131] In the cases where the main earner for the family was killed, one of the most notable consequences raised by community members was that the rest of the family struggled to afford food. In recent cases that involved additional armed actors acting with impunity, the extensive impacts are the same, as Naw M--- explained after her husband was killed by a KNDO Deputy Commander in Hpapun Township, Hpapun District, in 2015:

“I can’t work and earn a living on my own. I don’t even have money to buy MSG484 [common flavour enhancer] now. There is not enough shrimp paste now to make even a batch of pounded chilli paste.”

Naw M--- (female, 43), P---village, Bu Tho Township, Hpapun District/ northeastern Kayin State (interviewed in February 2015)[132]

Not only was an earner removed from the family, but families often explained that they found themselves having to pay out significant costs for healthcare. In one incident from 2015 Saw A--- was shot by BGF soldiers and fellow villagers managed to get him to hospital, where he died. The subsequent hospital costs of 900,000 kyat (US$761.35) had to be covered by his family and in order to manage the wife of Saw A--- demanded compensation to the battalion:

“How many soldiers [are there] in a battalion? You have to take one month’s salary from all of them and give [that money] to me [to support me] during one month.”

Villager quoted in an Incident Report written by a KHRG researcher, Bu Tho Township, Hpapun District/northeastern Kayin State (published in September 2015)[133]

However, in this incidence there was no compensation paid to the widow, and like many families they were left to fend for themselves without their family member. These consequences are very similar to those reported after torture, which also interrupts normal life; it removes family members who provide income,[134] makes them unable to continue their work and at times can lead to high healthcare costs.[135] For example, a villager from Dooplaya District suffered a dislocated shoulder during torture in 1997 and then ‘couldn’tholdanythinginhishandsanymore’,[136] and another villager from Toungoo District reported in 2016 that the village head had problems with his vision because of torture in the past.[137] The only difference between killing and torture is that the villager is able to return home if they survive the torture. However, this does not mean that they return to their community the same as they were before, as they often can no longer work to support their families.

Violent threats made against villagers, in both the conflict and the ceasefire period, can also be seen to have impacted upon villagers livelihoods. Villager’s frequently reported facing insecurity around access to their land, their homes and maintaining their livelihood, because of violent threats. This is demonstrated by a Muslim villager, Maung A---, from Thandaunggyi Township, who faced threats from the villages’ chairman of religious affairs, U Myo Tint, to leave the village. In 2015 Maung A--- described the impact that the threats had on him both emotionally and economically:

“Therefore,I cannot work freely during the day or sleep very well at night; I have to [always] be aware of the risk he [poses]. He would come into my house and insult me, shouting at me and then go back and come back again and keep complaining about me.”

Maung A--- (male, 34), Thandaunggyi Township, Toungoo District/ northern Kayin State (interviewed in March 2015)[138]

The effect of these intimidations on Maung A--- not only affected his ability to look after himself but also his ability to keep working. This is because villagers often feel fearful when faced with threats, and are then limited in their decision making ability. As threats are frequently used to coerce someone into doing something that is not in their interests, the fear that threats evoke means that the ultimate aim of the threat usually comes to fruition.

Furthermore, threats are now more commonly linked to land issues and land confiscation,[139] demonstrating that villagers’ right to land is restricted and they are denied full autonomy over their living situation.[140] In one case from 2015, Ma A--- reported that the Myanmar government issued a threat of jail to enforce relocation, as the land had been designated as a forest reserve and she was told:

“‘You all must provide your signatures.You must finish demolishing your houses in seven days’...If we did not provide our signature, we were going to have serious action taken against us and then putin to jail.”

Ma A--- (female, 43), Hpa-an Township, Thaton District/ northern Mon State (published in August 2015)[141]

Eventually the villagers’ homes were destroyed and the villagers were forced to flee. Despite having KNU documents for the land, the threats from the Myanmar government overturned the choice the villagers had made to remain and live on that land. Therefore it is clear that the insecurity villager’s feel when faced with violent threats has a negative impact on their lives, which can easily be identified in their livelihood and their ability to work.

The extensive livelihood destruction caused by violent abuse over the 25 years of KHRG reporting cannot be separated from other abuses and concerns raised by Karen villagers throughout this report. Livelihood vulnerabilities have been further aggravated throughout KHRG’s reports due to arbitrary taxation and extortion on finances and crops, continued displacement, inadequate health care and the poor treatment of Karen civilians in Myanmar government hospitals, inadequate access to and standard of education, and land confiscation, creating an oppressive cycle of abuse for affected civilians, families and communities and few opportunities to mitigate and manage these vulnerabilities.

The oppressive cycle of abuse, in which violent abuse was central, worked to undermine the structure of society in southeast Myanmar. Violent abuse has had a significant effect on communities in southeast Myanmar, with families being significantly challenged through extrajudicial killings, and on a wider scale, community cohesion has been hindered by torture and the displacement that came from ongoing violent abuse.

The wide scale killing of villagers during the conflict years means that there are a large number of families in southeast Myanmar living with the grief and hardship that follows the loss of a loved one. When a family member is killed, particularly in a violent way and without justice, the lasting effect is often emotional and painful,[142] which was strongly articulated by Naw M---, when she described the murder of her husband by a KNDO Deputy Commander in 2015:

“I don’t feel any good. I would say it honestly. People say that husband and wife have only one heart. I felt pity on him [my husband] but I could not help. I can’t resurrect him. So, I have to work and live poorly.”

Naw M--- (female, 43), P--- village, Bu Tho Township, Hpapun District/ northeastern Kayin State (interviewed in February 2015)[143]

The effect of the death of a loved one is often dramatic, and as the conflict in southeast Myanmar has been long-lasting, many community members have experienced losing multiple members of their family. For example, Saw Hs--- recounted how his son was shot on sight by the Tatmadaw in 2007, but also recounted the loss of close family members in the 1990’s:

“We were shot at by the SPDC [Tatmadaw] soldiers immediately so we didn't have time to care for each other. At that time one of my children was just three months old. She was lost and my wife also died. One of my relatives found the body of my wife.”

Field Report written by KHRG researcher, Nyaunglebin District/ eastern Bago Region (published in January 2008)[144]

Villagers demonstrated how they coped with and survived through these indiscriminate killings, however, the absence of justice for these killings impeded their ability to reconcile themselves with their loss. The impact of the destruction of families is further compounded by the displacement that violent abuse, in collaboration with other abuses against Karen civilians, caused, breaking up networks not only of families but of entire communities. Additionally, the Tatmadaw tactics of extrajudicial killings and the loss that Karen families and communities continue to live with make suggestions of ‘forgive and forget’[145] unpalatable.

Individuals faced significant losses during the conflict and one source of support would have been the wider community, however, this was seriously hindered as the cohesion of communities was undermined by the targeted abuse of village heads. Village heads were frequently considered to have the responsibility to solve problems for the armed actors, and to be the first point of contact for Tatmadaw and DKBA (Buddhist) when entering villages or making orders, and failure to do so often resulted in torture.[146] As a result, villagers were unwilling to act as village head and the frequent turnover of village heads resulted in a lack of consistent leadership in some communities,[147] undermining village cohesion and security. The risk that the village heads put themselves in is clearly demonstrated in an interview with Saw AaD--- from Dooplaya District in 1998:

“One of the headmen is named Saw AAt---, he is from AAu---near Saw Hta. The Burmese soldiers [Tatmadaw] knew that he was the headman and that there were army people around to defend his village, so they put him in a pit in the ground and asked him how many guns were in the village. They said that if he didn’t give them the guns they would kill him... Last hot season [earlier in 1998], there was a headman named Saw Aac---. The Burmese didn’t make him dig a pit for himself like xxxx, but they tied him up and hung him above the ground and then beat him.”

Saw AaD--- (male, 40), AaE--- village, central Dooplaya District/ southern Kayin State (published in November 1998)[148]

Since the preliminary ceasefire there has been a lack of cases of village heads being subjected to torture and armed actors do appear to have reduced their targeting of village heads. However, this is not to say that village heads are no longer victims, but the few examples appear to be perpetrated by rogue armed actors. For example, in 2015 a village tract leader was tortured by a former KNLA commander, Pah Mee,[149] in Hpapun District. In this case, the village tract leader appears to have suffered regular beatings at the hands of the commander, which had a significant impact on the victim.[150] Not only does torture significantly impact the victim but it undermines the structure of communities, as villagers are still unwilling to act as village head,[151] which can be seen as a legacy of the past abuses.

Agency

During the conflict, when it posed a severe risk to villagers if they were to confront the armed group directly or request compensation, villagers asserted their agency through avoiding encounters with armed groups that might lead to violent abuse, particularly Tatmadaw. Reports from the conflict period show that villagers placed a greater importance on the avoidance of situations that could lead to violent abuse, including limiting freedom of movement near army camps, village heads refusing demands to attend meetings at army camps,[152] and villagers hiding or fleeing when Tatmadaw columns were approaching.[153] Although the responsibility for ending abuse altogether can only be placed on the armed actors, the agency that villagers demonstrated shows that villagers were active in protecting and shaping their own lives. As was explained in one 2006 KHRG report:

“This active engagement with the structures of power is missed when they are portrayed as helpless victims whose situation is solely determined by factors external to themselves, such as the abuses of military forces or the provision of international aid.”

Thematic Report written by KHRG researchers, Toungoo, Hpa-an, Dooplaya, Hpapun, Mergui-Tavoy, Thaton, Nyaunglebin districts/Kayin State (published in November 2006)[154]

In addition to actively avoiding and preventing abuse, many community members also demonstrated methods of compromise to stop threats from erupting into violence, even when faced with extreme levels of violence. In one case in 2007 a village head faced the threat of death, when he told a KPF Commander that the village would be unable to meet his demands for charcoal or payment of 100,000 kyat (US$100.00):

“[KPF Commander] Saw Dah Gay rejected this proposal, fell into a rage, pulled out a grenade and threatened to crush the village head’s skull.”

Field report written by a KHRG researcher, Dooplaya District/ southern Kayin State (published in October 2007)[155]

In order to prevent this violence, the village head persuaded the KPF Commander to accept a pig worth 35,000 kyat (US$35.00). This demonstrates that in the face of potential violence some villagers were still able to find means to dispel the immediate threat of death; however, this does not mean that the compromise was fair or just. In fact, once the pig was delivered to the KPF Commander he continued to demand payment of 100,000 kyat (US$100.00). Evidently, agency tactics allow villagers to mitigate and avoid violent abuse by armed actors; however, a more long term solution to these abuses would be to hold armed actors to account over their actions.

As examples of torture and extrajudicial killings have decreased since the preliminary ceasefire, villagers are finding that they no longer have to take evasive or preventative action as often, which could allow them to seek more avenues for justice. Nevertheless, villagers have still reported using strategies to avoid, report or challenge the use of torture by powerful actors. For example, families have paid to have relatives released when they have been arrested, and in some cases victims have tried to escape from the armed groups[156] or attempted to report the abuse to the relevant authority.[157]

Likewise, women continue to report having to take evasive action to prevent GBV, as it has remained a constant abuse across the 25 years of KHRG reporting. The problem with discussing agency and GBV is that the responsibility is often placed upon the women to prevent the abuse, either by hiding,[158] fleeing or fighting back.[159] When in reality there should be more emphasis on promoting gender sensitivity within southeast Myanmar, educating men not to attack women and encouraging women to report the crimes. Part of the reason that the responsibility remains with the women is because, throughout the 25 years of KHRG reporting, women who have experienced GBV have faced shame and stigma within their communities in southeast Myanmar,[160] which continues to hinder their ability to speak out and seek redress. Reports since the preliminary ceasefire suggest that some cases of GBV are now dealt with at a local level, for example by CSOs such as KWO and village heads.[161] However, often when women report the abuse that they have suffered, either to village leaders, the KNU leaders or the relevant Myanmar government departments, women are finding that their cases are not being acted upon or that they are not receiving adequate justice.[162] Therefore their main agency tactic remains one of avoidance of armed actors, which does nothing to address the structure of abuse against women embedded since the conflict, the continued impunity of armed actors, or the ongoing presence of armed actors in southeast Myanmar.

Further to the obstructions of social stigma and impunity, there are additional, sometimes self- imposed, barriers that villager's view as insurmountable. In their recent engagements with the Myanmar justice system, villagers highlighted a number of obstacles to formal justice, which included distance to the courts,[163] fees and a lack of Burmese language skills,[164] as well as a lack of witness protection.[165] For example, an Incident Report on the rape of Naw Ao--- in 2014 explained that:

“After it was handed to the police, he had to open the case and face the courts.However, as the victim’s family lacked knowledge about the law, as well as money, the victim faced problems.”

Incident report written by a KHRG researcher, Thandaunggyi Township, Toungoo District/northern Kayin State (received in March 2015)[166]

In spite of both the self-imposed and external barriers, it is essential that villagers take action to report abuses and pressurise armed actors to be held to account, so that the ongoing impunity of armed actors who have committed abuses changes. Seemingly in acknowledgement of this, villagers continue to voice a desire for justice, regardless of the length of time that has passed since the violent abuse. As was highlighted by the cousin of Naw A---, who was commenting on the rape that Naw A--- suffered because of a DKBA (Benevolent) solider in 2015:

“It is good that if she [victim] reports the case to the leader so that it will not happen in the future. If we just keep things as is, he might come [back] in the future because he might think that he has done it [rape] and no action has been taken against him so he might keep doing it.”

Naw A--- (female, 45), Ab--- village, Kawkareik Township, Dooplaya District/southern Kayin State (interviewed in July 2015)[167]

Although the active avoidance of violent abuse has diminished, by demonstrating a desire for justice villagers show that their methods of agency have changed and developed. As more villagers push for fair and adequate justice, the barriers that they face begin to be challenged and in the future may be overcome. Nevertheless, it is clear that impunity still exists and the relationship between Karen civilians and armed groups remains fragile and scarred. Impunity for armed actors means the villagers’ safety is still not guaranteed and will continue the cycle of violent abuse against community members. Both the Myanmar government and KNU need to play a role in ensuring that villagers have access to a fair and free judicial system, as villagers can only play a role in placing pressure on the governing authorities, but real, lasting, beneficial change must come from the governing bodies in southeast Myanmar.

The following case studies highlight villagers’ voices to create an understanding of the full extent of the suffering that previous and continued abuses have had on their lives in southeast Myanmar. Two case studies will be examined, one detailing an example of GBV from 1999, which demonstrates the extent of the violence that women lived with during the conflict, the emotional and physical trauma that they faced and the long-term effect it had on them. Followed by an example of threats from the ceasefire period, which highlights how violent abuses are now perpetrated by more than just the armed groups, the impunity that armed groups continue to experience and how threats have been incorporated into business practices in southeast Myanmar.

In this case, published by KHRG in 1999, seven female villagers from AAv--- village, Kyaukkyi Township, were arrested by Tatmadaw Infantry Battalion #60 and detained for 15 days. Alongside abuses of arbitrary arrest, torture and violent interrogation, at least two of the women, aged 28 and 51, reported that they were raped.

The 51 years old women gave her account of the atrocities she experienced including the use dehumanising language and the threat of execution that accompanied the GBV:

“He said that ifwe lied to himhe wouldkill us, but if we ‘gavethemour meat’he would release us with ourlives.”

The threat of violence was continuous throughout the sexual assault, which highlights the traumatic nature of the abuse:

“I apologised but told him not to do that to me because I am old. Then he said, ‘Then I must kill you, Mother’. He said it slowly, then he forced me to lay down and hold his penis. I didn’t dare hold his penis, but he drew my hands and forced me to hold it, and he grabbed my buttocks. … While he was doing it he threatened me with a dagger, he touched it to my chest, neck and armpits.”

The female village also reports the mental torture that accompanied GBV during their 15 days of arbitrary arrest and detention:

“An other time after that, they called us in at midnight. They said they would kill us, they touched our chests with a dagger and told us to pray.”

Notably, the 28 years old female villager, Naw H---, experienced sustained sexual assault, so much so that the Tatmadaw were unwilling to release her with everyone else after 15 days and abuses against her continued:

“They didn’t release Naw H---.She was handed over to #349. The #349 troops arrested her, locked her in the stocks and then sent her to Shwegyin.They sent her to their Battalion camp in Shwegyin and put her in a cell. Then a Corporal with 2 chevrons came and called her, he took her to the Battalion [HQ] and turned off the light. He was with her for 2 hours. When the soldiers went to look, he had raped her. … After that we came to the hills and didn’t hear any more about her. She is still in jail.”

Female villager quoted in report written by a KHRG researcher, Nyaunglebin District/eastern Bago Region (published in May 1999)[168]

Furthermore, the interviewee mentioned that she was aware of another woman, aged 25 years, who was also raped and mentally tortured. This suggests that this was not an isolated case of sexual assault but a common abuse, which affected a wide range of women during the conflict years.

This interview details how Saw H---’s land was confiscated by Kyaw Hlwan Moe and Brothers Company in 2015, and how he faced threats from the company and the BGF to force him to stop working on his land and to relocate.

This case clearly demonstrates the close relationship between armed groups and private companies, as the unknown battalion of the BGF was described as providing security, which means that threats from a private company often come through or are in partnership with military powers:

“They [BGF’s soldiers] fired guns about 40 to 60 times per day. But they did not intend to kill people.Their purpose was to threaten people.”

The collaboration between the private companies and armed groups means that the threats villagers face are often violent. In this case, the BGF shot at the villagers, which had significant consequence in that the villagers stopped using their land:

“Before, in this area [Pa Tok], farmers nearby worked on it. All villagers around that area collected the wild vegetables and fruits, and worked on that land. Now, nobody dares to go in that area.”

The interview also highlights the long term impact that these violent threats can have, and it also notes the resources that the company has at its disposal, to be able to keep people off their land:

“But most people dare not work anymore, because they threatened people who work in the farms. It has been three or four years [happening like this]. It is not just happening for the previous

months, it has been years. If the farmers plough in their own farm, they [the companies] will take action with an article [criminal charge]. They can say which articles, I do not know which articles.”

Saw H--- and other villagers did demonstrate agency by writing a complaint letter, however, it reveals the challenges the community members faced when trying to challenge a private company and the BGF. Saw H--- summarises the significant impact the violent threats have had, which highlights why the private company was able to achieve its aim of displacing people.

“There is no mediation but only threaten in gof the villagers. It has been four to five times that I arrived at the [Myanmar government] district office. I went by myself. The last time, nobody went [with me]. They knew that the authorities would arrest them so they dared not go. So I went there alone. There are many people who are illiterate. I want them [government authority] to understand us. These people are the local people, who worked for the country in the past even if they are illiterate. But they [the company and government] want us to move out from our land. If I look at my uncle, he is illiterate but has been farming since he was young. Look now, the farms that he has worked for many years, for over 40 years have been confiscated now. What do we do now? We do not get back our land and just have to stare [look at what company does] like this? Moreover, these people from an armed group came, fired guns and threatened us. And we [BGF and villagers] are the same Karen ethnicity.”

Saw H--- (male, 36), Hpa-an Town, Hpa-an District/central Kayin State

(published in August 2016)[169]

This photo was taken on October 7th 2014 in AAz--- Village, Dwe Lo Township, Hpapun District. It a photo of Naw ABa---, a mother of an 11 year old girl called Naw ABb--- from AAz--- Village. She reported that her daughter was sexually assaulted on her way to school by a teacher from another village in September 2014. [Photo: KHRG][171]

Foundation of Fear: 25 years of villagers’ voices from southeast Myanmar

Written and published by Karen Human Rights Group KHRG #2017-01, October 2017

“There’s nothing we can do – there’s always a soldier there, pointing a gun at us.”

Female villager quoted in a report written by KHRG researcher, Hpa-an, Thaton, Nyaunglebin districts/Kayin State (published in February 1993)[1]

“We need safety. We also need social organisations for local development [and to provide self- defence training] so that the villagers can be safe from danger.”

Naw Az--- (female) Kyainseikgyi Township, Dooplaya District/ southern Kayin State (Interview received in January 2016)[2]

Keyfindings

1. Since the preliminary ceasefire, the use of extra judicial killings and torture by armed groups, most commonly Tatmadaw, has decreased. However, violent threats continue to be

used to advance the interests of armed groups, as well as the Myanmar government and private companies. These threats are frequently of a serious and violent nature, which

means that community members are often fearful of retaliation if they report the abuse, which deprives them of justice.

2.Over 25 years of KHRG reporting, villagers’ reports of GBV have not declined. Women continue to report feeling insecure in their own communities, which is inpart because of the use

of GBV as amilitary tactic during the conflict, as well as the ongoing violence perpetrated by other community members. Women also report a lack of justice, as frequently the abuse is

not investigatedfully or the perpetrat or is not given an appropriate punishment.

3. Torture continues to be used as ameans of punishment and interrogation by some members of the Myanmar police and armed groups, which has led to reports of miscarriages

of justice and acriminal is ation of villagers by the judicial system.

4.Extrajudicial killings by armed actors have decreased since the preliminary ceasefire; however, the legacy of these killings means that villagers continue to feel unsafe in the presence

oftheTatmadaw.

5.The weak implementation of the rule of law and lack of access to justice results incases of violent abuse remaining unpunished, with victims remaining without justice or closure.The

systematic violent abuses committed by armed actors against civilians during the conflict remain unpunished.