Analysis of KHRG's field information gathered between January 2011 and November 2012 in seven geographic research areas in eastern Myanmar indicates that natural resource extraction and development projects undertaken or facilitated by civil and military State authorities, armed ethnic groups and private investors resulted in land confiscation and forced displacement, and were implemented without consulting, compensating or notifying project-affected communities. Exclusion from decision-making and displacement and barriers to land access present major obstacles to effective local-level response, while current legislation does not provide easily accessible mechanisms to allow their complaints to be heard. Despite this, villagers employ forms of collective action that provide viable avenues to gain representation, compensation and forestall expropriation. Key findings in this report were drawn based upon analysis of four trends, including: Lack of consultation; Land confiscation; Disputed compensation; and Development-induced displacement and resettlement, as well as four collective action strategies, including: Reporting to authorities; Organizing a committee or protest; Negotiation; and Non-compliance, and six consequences on communities, including: Negative impacts on livelihoods; Environmental impacts; Physical security threats; Forced labour and exploitative demands; Denial of access to humanitarian goods and services; and Migration.

I. Introduction

"The two [Tatmadaw] battalions built their camps and confiscated all T--- villagers' lands. Not only T--- villagers, M---, W--- and N--- as well. They didn't confiscate the land systematically in the past. We did farming and could pay them a percentage. In 2012, they will completely confiscate the land. They asked us to sign it away. We don't want to sign and we are against them. They said it belongs to them. It belongs to the State. T--- villagers have no rights."

Saw N--- (male, 60), T--- village, T'Nay Hsah Township, Hpa-an District/ Central Kayin State (Interviewed in June 2012)[1]

"I want to say that our minds shouldn't change because of a company that came and mined for gold. Maybe the company tricked us into selling a lot of our land and orchards by telling us about a dam to make us afraid. They said that they will build the dam and, villagers who have their land close by became afraid, and they wanted to sell all of their properties and go to mine gold. … If the citizens really try to stand stable in their place, I think they can. If they are in fear, if there are a lot of soldiers confronting them, they won't have enough energy to protest."

Saw Th--- (male, 26), B--- village, Dweh Loh Township, Papun District/ North Kayin State (Interviewed in April 2011)[2]

Throughout 2012, villagers in eastern Myanmar described land confiscation and forced displacement occurring without consultation, compensation, or, often, notification. Such displacements have taken place most frequently around natural resource extraction, industry and development projects. These include hydropower dam construction, infrastructure development, logging, mining and plantation agriculture projects that are undertaken or facilitated by various civil and military state authorities, foreign and domestic companies and armed ethnic groups. Villagers consistently report that their perspectives are excluded from the planning and implementation of these projects, which often provide little or no benefit to the local community or result in substantial, often irreversible, harm.

Business and development projects have increased substantially in the wake of Myanmar government reforms and the ceasefire signed with the Karen National Union (KNU).[3] While the cessation of armed conflict has made the area more accessible to investment and commercial interests, eastern Myanmar remains a highly militarised environment.[4] In this context, where abundant resources provide lucrative opportunities for many, and a culture of coercion and impunity is entrenched after decades of war, villagers understand that demand for land carries an implicit threat.

Displacement and barriers to land access arising from these projects present major challenges at the local level. Where land is forcibly taken, fenced-in, flooded, polluted, planted or built upon, the obstacles to effective local-level response are often insurmountable. Even where villagers manage to overcome barriers to organising a response, current legislation does not provide any easily accessible mechanism to allow their complaints to be heard.

Despite this, villagers employ forms of collective action that provide viable avenues to gain representation, compensation and to forestall expropriation. Villagers' ability to navigate local power dynamics and negotiate for unofficial remedies, championed in some cases by an increasingly active domestic media, is forging new and promising avenues for collective action and association.[5]

This report draws on villagers' interviews and testimony, as well as other forms of documentation including photographs, film and audio recordings, collected by community members[7] who have been trained by KHRG to report on the local human rights situation. The documentation received has been analysed for cases in which villagers' access to and use of land has been disrupted, highlights trends of abuse, and details obstructions to the formal channels of complaint or redress that villagers face. The report closes by outlining the serious consequences created by such abuses and the lack of meaningful inclusion of villagers in the making of decisions, which affect them so fundamentally.

The objective of this report is to foster a better understanding of the dynamics and impacts of natural resource extraction and development projects on the ground by presenting a substantial and recent dataset of villagers' testimonies in eastern Myanmar. This report aims to broadcast the perspectives of villagers in eastern Myanmar to actors throughout the country and the international community. The complaints recorded in this report are important, and deserve attention, first and foremost because they represent the lived experience of villagers who are being directly affected by the actions of myriad actors in a rapidly changing Myanmar. It is intended to assist all stakeholders, including Myanmar government officials, business actors, potential and current investors, and local and international non-profit organisations, as they work to: (1) acknowledge and avoid the potential for abuse caused directly or in complicity with other actors; (2) further investigate, verify and respond to allegations of abuse; (3) address the obstacles that prevent rural communities from engaging with protective frameworks; and (4) take more effective steps to ensure sustainable, community-driven development that will not destabilize efforts for peace and ethnic inclusion.

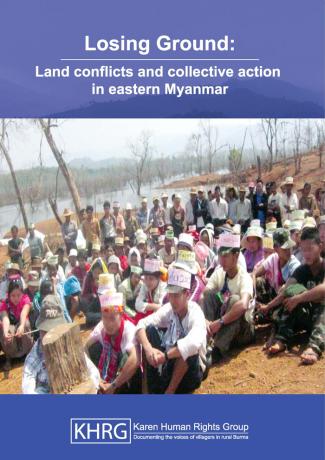

This photo was taken on March 12th 2012 and shows over 400 villagers from Shweygin and Kyauk Kyi Townships protesting the Shweygin Dam in Nyaunglebin District/ Eastern Bago Region. The community member who took this photo told KHRG that villagers chanted three requests of the Government in Burmese: "No continuation of the dam construction. Compensation for lost farmland flooded by the dam. Let the water flow naturally."[6] [Photo: KHRG]

The first photo was taken on July 15th 2012 and shows the damage to villagers' homes that resulted from gold mining near the Baw Paw Law River in Papun District. The second photo was taken on August 1st 2012 and shows an active construction site in the Toh Boh area, Tantabin Township, Toungoo District, run by the Shwe Swan In Company. According to villagers in the area, the Toh Boh Dam operations, including the construction of large buildings to house hydropower generators in Toh Boh village, have resulted in the displacement of villagers. The third photo was taken on August 9th 2012 and shows the flooding of villagers' homes in Let Kauk Wa village, Nyaunglebin District. The community member who took these photos reports that the flooding was caused by the Shwegyin Dam. [Photo: KHRG]

Footnotes:

[1] See Appendix 1: Source document/T'NayHsahPlantationAgriculture/2012/5.

[2] See Appendix 1: Source document/PapunBilinRiverDam/2011.

[3] The data analysed for this report was received by KHRG from January 2011-November 2012 but covers a range of development projects occurring from 1999 onwards. The increase is demonstrated in the detail provided in Section VI: Projects under observation, which shows that incoming business, particularly by private companies, surpassed numbers in the previous years, corresponding to new opportunities presented by the November 2010 general election and Myanmar government-KNU ceasefire. Of the 99 documents that raised issues related to natural resource extraction and business or state-led development projects, 60 raised incidents occurring after November 2010 and 34 raised incidents occurring since January 2012.

[4] The KNU and Government of Myanmar agreed to a ceasefire on January 12th 2012. Since then they have held several rounds of dialogue but this has not yet resulted in a concrete code of conduct or in resolution of political demands by the KNU. KHRG has published two commentaries considering villagers' perspectives on the ceasefire, and opportunities that it presents to address outstanding issues of the conflict, see "Safeguarding human rights in a post-ceasefire eastern Burma," KHRG, January 2012 and "Steps towards peace: Local participation in the Karen ceasefire process," KHRG, November 2012.

[5] Public protests against unilaterally-implemented natural resource extraction projects have been covered by the domestic media in Myanmar as well as the international media, including for example the halting of the controversial Myitsone dam on the Irrawaddy River, "Activists celebrate Myitsone dam victory," Myanmar Times, October 2011 and large-scale public protests at a copper mine in Monywa; see: "Peaceful demonstrations and the 'access to remedy' vacuum," Myanmar Observer, October 2nd 2012. Coverage of issues in ethnic areas is more limited, outside of ethnic media sources, for example: "Mine pollutions kills villager's plantations – government fails to act," Karen News, March 15th 2012. Media groups are encouraged to expand their coverage to ensure similar support for collective action across the country.

[6] This photo was taken on March 12th 2012 and shows over 400 villagers from Shweygin and Kyauk Kyi Townships protesting the Shweygin Dam in Nyaunglebin District/ Eastern Bago Region. The community member who took this photo told KHRG that villagers chanted three requests of the Government in Burmese: "No continuation of the dam construction. Compensation for lost farmland flooded by the dam. Let the water flow naturally."

[7] KHRG trains 'community members' in eastern Myanmar to document individual human rights abuses using a standardised reporting format; conduct interviews with other villagers; and write general updates on the situation in areas with which they are familiar. When writing situation updates, community members are encouraged to summarise recent events, raise issues that they consider to be important, and present their opinions or perspective on abuse and other local dynamics in their area. For additional information, see Methodology in the report by clicking link above.

Executive summary

Findings in this report are based upon analysis of KHRG's field information received between January 2011 and November 2012 across seven research areas, encompassing all or part of Kayin and Mon States and Bago and Tanintharyi Regions. For the purposes of this report, nine KHRG staff analysed 809 oral testimonies and written pieces of documentation received during the reporting period, as well as 209 sets of images. Of these 809 documents, 99 raised concerns or dealt with issues related to natural resource extraction and business or development projects in eastern Myanmar, including: hydropower dam construction, infrastructure development, logging, mining and plantation agriculture. These projects were undertaken or facilitated by various civil and military State authorities, armed ethnic groups and foreign and domestic companies.

Section II: Current Context reviews recent developments in Myanmar's laws and politics, and analyses how recent reforms by the Government and opening to the outside world could facilitate human rights abuse, as well as identifying potential opportunities to protect the rights of villagers in eastern Myanmar afforded by the changing situation. This section concludes by arguing that the rights identified as essential by villagers in eastern Myanmar closely track the rights protected under international law.

Section III: Trends of abuse in project implementation sets out four trends that are apparent based on the information received from villagers: lack of consultation; land confiscation; disputed compensation; and development-induced displacement. Section IV: Collective action, provides analysis of four collective action strategies described by villagers, adopted in response to the trends identified, which are: reporting to authorities; organizing a committee or protest; negotiation; and non-compliance. Further, six consequences on communities of natural resource extraction and development projects are analysed in the report in Section V: Consequences, namely, negative impacts on livelihoods; environmental impacts; physical security threats; forced labour and exploitative demands; denial of access to humanitarian goods and services; and migration.

Section VI: Projects under observation includes a table with summaries of the 99 pieces of information received by KHRG during the reporting period, and details abuses related to natural resource extraction, business and development projects impacting communities which, as a result, community-members working with KHRG are monitoring and documenting. The table is organized by project-type, including: hydropower dam projects, infrastructure development, logging, mining and commercial plantation agriculture. The full text of all 99 of these documents, also organized by project-type, is included in Appendix 1: Raw Data Testimony.

Key findings

During the reporting period, villagers across all seven research areas described natural resource extraction and development projects implemented unilaterally without engaging or informing project-affected villagers. Villagers reported that they were not consulted or informed before a project began, nor given an opportunity to enter into dialogue or request additional information. In some cases, villagers said that only village leaders were consulted or that partial information was provided about the realities of the project and how it would affect their land or livelihoods. (Section III: A)

During the reporting period, villagers across all seven research areas described land confiscation or obstacles to land use or access directly resulting from natural resource extraction or development projects. Villagers described land confiscation as a result of the project expansion and encroachment onto land adjacent to the project site, as well as the confiscation of land belonging to refugees and internally-displaced persons (IDPs). Villagers in some cases received explicit information from military or civilian officials that their land would be confiscated, that they would no longer be permitted to use it as they had previously, or that decisions regarding the use of their land had already been made in meetings between State or non-state authorities and companies to which the villagers were not invited. In other cases, villagers learned of the confiscation of their land only when construction workers arrived to survey and mark the project site. (Section III: B)

During the reporting period, villagers across all seven research areas described obstacles to securing fair compensation for losses or damages incurred during or after project implementation. Villagers described not being offered compensation, nor provided with an opportunity to negotiate for compensation, following development-based destruction of their land. Villagers also described undue pressure to accept compensation offered and negotiations during which development actors committed to compensation that was never paid or only partially paid. Villagers also described other obstacles to seeking redress, including an inability to afford and a lack of awareness about formal legal remedies. (Section III: C)

During the reporting period, villagers across six out of seven research areas described development-induced displacement or resettlement as a direct result of natural resource extraction and development projects. Villagers described explicit orders issued by military and civilian government officials for communities to relocate from targeted project areas, such as those to be developed for agri-business, infrastructure development or dams, and said that such orders were frequently accompanied by threats of violence for non-compliance. Other villagers described being forced of necessity to relocate due to the destruction of livelihoods and environmental degradation in or near project sites. (Section III: D)

During the reporting period, villagers across all seven research areas described communities' active attempts to prevent or mitigate negative impacts to their land and livelihoods in response to business and development projects. Forms of collective action described include: writing complaint letters to Myanmar government bodies, to the KNU or to private companies, in some cases including a list of damaged land or crops and quantifying the amount of compensation that should be given; organising public protests; forming committees to submit complaints and strengthen collective bargaining ability during negotiations with authorities; directly negotiating with company representatives, government officials or members of an armed group; or refusing to comply with verbal or written orders, in most cases related to a refusal to leave their land, or a refusal to sign away land claimed by authorities (Section IV: A - D).

During the reporting period, villagers across all seven research areas described serious negative consequences on communities' land, livelihoods and physical security due to natural resource extraction and development projects. Villagers describe destruction of agricultural activities and a lack of alternative livelihood options. Dam projects resulted in permanent flooding, logging led to deforestation and soil erosion, and agricultural or mining projects caused water contamination, posing health risks for villagers and livestock. Physical security threats were also described to occur around project sites, where local military authorities often had a financial stake in the project in question. Villagers described coercion to accept terms of compensation for confiscated land, and threats of physical harm for refusing or trying to negotiate the amount of compensation. Villagers described forced labour at project sites or providing money to pay for the project itself. In some cases, new projects have led to a denial of humanitarian access, where schools and hospitals were destroyed by new construction or closed in advance due to direct orders or threats of relocation. Villagers also described how some villagers have migrated to larger cities or across international borders, or sent their children to do so, in search of alternative employment opportunities. (Section V: A - F)

Serious obstacles undermine communities attempting to respond to business and development projects and limit their ability to prevent and mitigate negative impacts. The exclusion of local voices from development planning constrains rural communities' ability to raise concerns through engagement, or seek redress for damages through negotiation. Local communities lack knowledge of both details and impacts of projects and of the law, limiting their ability to negotiate or take action, and increasing their vulnerability to manipulation. Explicit and implicit threats of violence deter communities from proactively engaging authorities, particularly armed actors and private companies partnering with these actors for access to the area. Fear of violence is worsened by recent memories of violence and abuse related to decades of militarization, armed conflict and counter-insurgency.

Recommendations

Consultation and consent

-

Villagers are best placed to assess their own interests and the impact of development on their livelihoods. Their perspectives must be included in all decision-making.

-

All development actors must carry out environmental, health and human rights impact assessments prior to project implementation. These assessments should be carried out independently of the actor's interests, in consultation with project-affected communities and made publicly available in all local languages.

-

Development projects should be planned in consultation with local communities, with full disclosure of information relating to how the projects could affect their lands and livelihoods. Communities should participate in decisions regarding size, scope, compensation, and means of project implementation.

Customary land rights and usage

-

Government should protect existing land use practices and tenure rights, and acknowledge that local communities may recognise land title granted by multiple sources, including customary, colonial and local administrations.

-

Policy reforms should ascertain and respect the land rights of communities and individuals displaced by conflict.

Support for community solutions

-

Development actors should seek out and engage with local, broad-based, independent associations of villagers formed to address land issues, as well as local community-based organizations.

-

Domestic civil society should promote knowledge-sharing among and give support to independent associations across the country.

-

Media should expand their coverage of land conflicts in rural eastern Myanmar.

-

The Government and civil society should provide communities with training and educational resources about domestic complaint and adjudication bodies.

Ceasefire context

-

Business and development actors should ensure they do not become complicit in human rights abuses by carrying out good faith due diligence to ensure that their partners do not compromise the rights and security of local communities.