In this Interview, a local woman from Htantabin Township, Toungoo District, discusses how repeated instances of land confiscations have harmed her community.

- In 1993, the construction of the P’Thi Dam led to land confiscations and widespread displacement. Stripped of their land, many subsistence farmers became day wage labourers, working under difficult conditions. This land confiscation continues to impact the livelihoods of local people to this day. The displaced communities have yet to receive any compensation, or even to benefit from a connection to electricity. Despite this, villagers continue to reclaim their ancestral lands through consultation and court hearings.

- Since the construction of the hydropower dam, this community has faced a series of successive land confiscations by private companies. The remaining land has been confiscated by the Tatmadaw. Local plantations are being used for shooting practice, threatening the security of local farmers. The community wants the Tatmadaw to withdraw the camp from their lands.

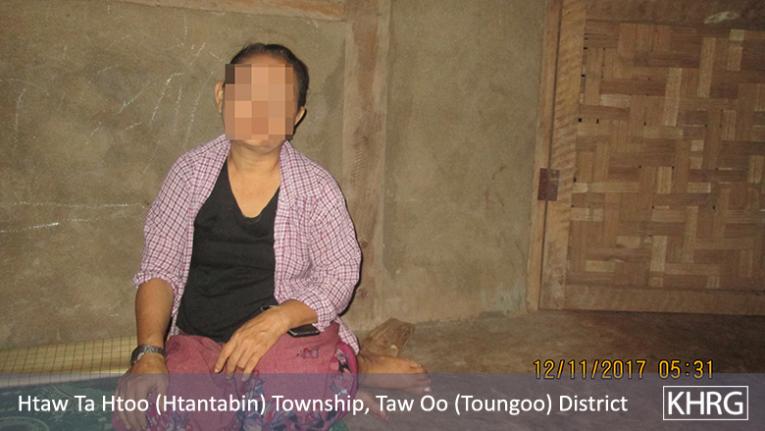

Interview | Naw W---, (female, 56), L--- village, Htantabin Township, Toungoo District (November 2017)

The following Interview was conducted by a researcher trained by KHRG to monitor local human rights conditions. It was conducted in Toungoo District in November 2017 and is presented below translated exactly as it was received, save for minor edits for clarity and security.[1]This interview was received along with other information from Toungoo District, including five other interviews and 15 photographs.[2]

Ethnicity: Karen

Religion: Christian

Marital Status: Married

Occupation: Plantation Worker

Position: Civilian

What is your name?

My name is Naw W---.

How old are you?

I am 56 years old.

What is your ethnicity and religion?

My ethnicity is Karen and I am Christian.

Where do you live?

I live in L--- village, Toungoo District.

How do you secure your livelihood?

I work on plantations.

Could you tell me about the challenges that you are currently facing?

I would like to tell you about the construction of a hydropower dam that has displaced local communities. When the construction of the hydropower dam began, we did not have anywhere to go because our lands were confiscated.

How long has the hydropower dam been operating?

They started building the hydropower dam in 1993.

How many villages have been affected by the construction of the hydropower dam?

Two villages were affected by the hydropower dam. These villages are L--- village and A--- village.

Did the company notify the local population before they began constructing the dam?

No, the company did not give prior notice to local communities.

How did they start building the dam?

They brought machines and excavators into the villages and dismantled the homes of the local people. They gave us an order to leave our village within five days. We found it difficult to find shelter and secure our livelihoods.

Where did local communities relocate to?

The hydropower dam was being built to the east of L--- village. Therefore, we chose to relocate to M--- village, located to the west of L--- village. We spoke with the village leaders of M--- and asked them for a place to settle. However, we did not report [our resettlement] to the Burma/Myanmar government, we did not obtain permission for relocation. Finally, we were able to settle in M--- village [in 1993, when the hydropower dam was under construction]. During that time, civilians did not have the opportunity to fight for their rights or confront the dictatorship in Myanmar. The fear of dictatorship endures within us to this day.

What are the most difficult challenges that you faced when you were displaced?

Our biggest challenge was securing our livelihoods after being displaced. This was difficult because people lost their plantations. People tried to find casual work to supplement their income. Some people migrated abroad, to other towns or to the jungle looking for a job. Many local people worked in the logging sector. Those who were logging the forest with elephants struggled very much. They had to do this job with no previous experience. In 2015, five people were killed by elephants while they were logging. Some people sustained leg and arm injuries during their work. Others suffered serious illnesses and then committed suicide when they could no longer tolerate their situation.

What challenges did people face after the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA)?

After the NCA was signed between the KNU and Myanmar government in 2015, local people were allowed to report land confiscations. However, we had to attend court several times to address our land confiscation case. We were sued for reporting land confiscations, and for fencing our lands to protect them. We attended court three times in one year because we were sued by the Ministries of Industry, which was operating rubber plantations [in our area].

Could you tell me more about your dealings in the court?

We were told that our lands would be given back to us if we took our land confiscation case to court. Therefore, we spent our time and money on this process. However, we are yet to get our lands back. We are in debt because we borrowed money from other people in our village to deal with the court costs. We had to deal with Aung Kyaw Oo, the representative of the Ministry of Industry in court. In 2016, the manager Aung Kyaw Oo sued us because we returned to our plantations and cultivated our lands. The company’s representatives see themselves as the landowners. They consider us to be trespassers.

o address this case, the village head asked the company representatives to consult with the community. However, they said that it was not their responsibility. To oppose the land confiscations, people fenced off their plantations. However, the company took [the fences] down. The company also hired people to patrol around the village. The people patrolling would carry knives and threaten people.

How many workers are in the company?

As far as I know, there are six people in the company.

When did the company start operation?

The company linked to the Ministry of Industry [Ministry of Industry #1 at the time of the incident] started operations in 1997.

Are they [under the authority of the] Myanmar government?

In the past, the company said that the rubber plantations cultivated by the Ministry of Industry #1 were under the authority of the Myanmar government. However, the township administrator said that, at present, the company manager Aung Kyaw Oo took over the operation. Even though Aung Kyaw Oo said that he holds the land grant from the Ministry of Industry, it was not registered in the Township office.

How much land was confiscated in your village?

I do not know the total amount of confiscated land in my village. In 1993, some people had 5 acres, 6 acres, 10 acres and 20 acres confiscated. In the consultation meeting held with the company and the local population, Aung Kyaw Oo, the company manager, said that around 70 acres of land were confiscated in L--- village.

When did he say this?

He said it in the consultation meeting with the local community in L--- village.

Do you hold a land form #7?

We do not hold a land form #7,[3] but we have a land tax receipt that we received from the Myanmar government. When the company came to the village, they asked all local community members for their land titles. The company declared: “the land is not yours anymore because we confiscated your lands, so you should give your land title to us”. None of the villagers received compensation for lands that were confiscated.

What did the companies do after they confiscated the landof the local community?

The U Than Myit Agriculture Company and the Ministry of Industry #1 established large-scale rubber plantations. They did not return land to the villagers.

Are there any other companies that confiscated land from local communities?

At first, 30,500 acres of lands were confiscated for the construction of the hydropower dam. Then, the U Than Myit Agriculture Company and the Ministry of Industry #1 established rubber plantations. In L--- village, U Than Myit Agriculture Company confiscated about 70 acres of land owned by villagers. In addition to this, the Ba Yin Naung military school confiscated an additional 1,851 acres of the remaining land. Actually, when the dam project was proposed, its administrator declared that villagers would be able to work on the land that was left-over [from the dam project]. However, we could not do that because all of the remaining lands were ultimately confiscated by other companies.

So the first confiscation was for the hydropower dam construction, followed by the Ministries of Industry #1. After that, the U Than Myit Agriculture Company confiscated more land. Then, land was confiscated for the Ba Yin Naung Military School. When did the military school confiscate land?

The Tatmadaw confiscated land for the Ba Yin Naung Military School in 2000. They confiscated all the land that was left over following the previous confiscations.

How did the Tatmadaw use the land that they confiscated?

They used it for a military shooting range and training grounds.

How did the villagers feel about the Ba Yin Naung Military School?

We were afraid when Tatmadaw soldiers had shooting practice in the plantation close to the village. The Tatmadaw usually notified the local community the night before they had shooting practice. Villagers had to run away as soon as they would hear firing around their houses.

When would Ba Yin Naung Military School have firing practices?

They had firing practices once every four months, as recently as November 9th, 2017. They plan to have another firing practice in March 2018. Could you give us suggestions how to protect ourselves from Tatmadaw firing in the village? We really want the Tatmadaw camp to withdraw.

We cannot protect you from the Tatmadaw directly. The only way KHRG can protect the local populations is by advocating to decision makers.

All of our lands were confiscated by companies. None of the companies are considering to give the land back to us.

What is the situation like in the neighbouring village of A---?

The community of A--- were also victims of land confiscations but they were more fortunate than us since their village is located in a KNU-controlled area. They received some material support [from NGOs] such as clothes, blankets, cookers, bowls, and plates. They also had electricity installed in the village.

In comparison, our village did not receive any support or compensation because it is located in Bago Region [under Myanmar government control].

Are there any NGOs that distributed material support to your village?

No, there were no organisations that distributed material support to our village. Villagers believed that his depended on the village head. Our village was flooded [due to hydropower dam]. The local population did not receive electricity unlike many communities that were not negatively affected by the construction of the dam.

The project manager of the hydropower dam Aung Kyaw Oo negotiated with the village head and the village elders before construction. The village head had the opportunity to advocate on our behalf. Instead, the village head negotiated with the company for his own benefit. The village head stood with the liars. This is why every department and company could enter our village and confiscate all lands. We were also sued by the companies when we tried to defend our lands. Unfortunately, in 2016, we did not win this case because our village head cooperated with the dam project manager Aung Kyaw Oo.

Who is your village head?

His name is Htee Su Mo. He is from Ngway Taung K’Lay village. He is Bamar. He is not a native from L--- village.

Are you still dealing with the court?

Yes, we are still dealing with the court. This coming Tuesday, we will be attending a court hearing with the company responsible for the hydropower dam. Then, we also plan to meet with the Township administrator to sue the Ministries of Industry representative Aung Kyaw Oo. We decided to sue them because we believe that we are right.

How many villagers are going to the court hearing?

I do not know exactly how many times villagers were sued by the company. As for me, this is the third time I have been sued because of the dam project. We won the very first court [case] that was held in 2007. In 2016, we did not win the second case because our village head supported the corporate interests.

How many households live in your village?

There are 68 households.

Are there any healthcare services?

We do not have a clinic in the village. We only have [access to] a traditional midwife who also knows traditional medicine.

Are there any schools in the village?

There is a middle school that goes from kindergarten to Standard Seven. It is a Myanmar government school.

What are the school fees?

Primary school [from kindergarten to Standard Four] is free.

Are there any NGOs that provide educational support to the village?

No.

Would you like to share any other information?

I would like to say that we want our land returned to us so that we can keep working on our plantations.

In addition to this, we do not have any health care services in the village or a library for local students. Our village was flooded when the hydropower dam was built, but affected villagers did not receive any electricity. The company did not provide any sanitation facilities or build a road for the villagers who had to relocate. We have been facing these issues from the beginning of the construction of the hydropower dam.

If we get our lands back, we can improve our village and overcome these challenges. Since we cannot recover our lands, we want compensation for our damaged homes and the confiscated lands. We want the national government to take those affected by commercial projects into consideration.

Footnotes:

[1] KHRG trains community members in southeastern Burma/Myanmar to document individual human rights abuses using a standardised reporting format; conduct interviews with other villagers; and write general updates on the situation in areas with which they are familiar. When conducting interviews, community members are trained to use loose question guidelines, but also to encourage interviewees to speak freely about recent events, raise issues that they consider to be important and share their opinions or perspectives on abuse and other local dynamics.

[2] In order to increase the transparency of KHRG methodology and more directly communicate the experiences and perspectives of villagers in southeastern Burma/Myanmar, KHRG aims to make all field information received available on the KHRG website once it has been processed and translated, subject only to security considerations. For additional reports categorised by Type, Issue, Location and Year, please see the Related Readings component following each report on KHRG’s website.

[3] Land form #7 is the land grant required to work on a particular area of land. In Burma/Myanmar, all land is ultimately owned by the government.